“Meet the flight from Berlin at London’s first Airport!” Jimmy read in letters stencilled in indelible ink on the knot of the noose from Execution Dock. “There’s a time and date, too. What was London’s first airport? Heathrow?”

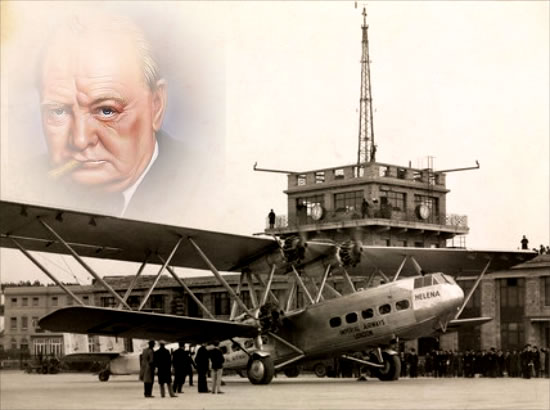

“Croydon,” Vicki answered quite nonchalantly. “Daddy took me there once when I was eight – to see the planes landing and taking off. It was really nice. We had tea in the hotel next door, built to accommodate passengers waiting for planes. It’s a really beautiful place – all 1920s neo-classical style, lots of crisp white plaster and long, slender windows.”

Jimmy wasn’t really interested in neo-classical architecture as such, but the chance to see some old-fashioned aeroplanes in full working order appealed to him. He WAS interested in engines and mechanics of all sorts and was hoping to get into college to study engineering if his results were good enough. He had spent rather too many years as the class dunce, paying no attention to his lessons and now he had to catch up fast. He wouldn’t have stood a chance at all in the written part of the examinations except for Vicki’s father, the remarkable man everyone called The Doctor, who had given him some extra theory lessons. He could, at least, write a coherent paragraph or two about Boyles Law or Bernoulli's Principle without panicking. He even knew the basic laws of Thermodynamics when a few years ago he would have struggled to even spell the word!

An afternoon watching planes take off and land was right up his street. Vicki could enjoy tea on the terrace while he got up close to some fascinating engines.

“Commit no Nuisance in Dickensian Southwark?” Earl laughed. “Are we likely to commit a nuisance?”

Sukie laughed, though the clue puzzled her.

“We lived in Southwark when I was born,” she said. “We moved to where we are now after our house was burnt down, though I was only a baby then and I don’t really remember much. I don’t remember much about Dickens, either. I really don’t like his books except for A Christmas Carol. Everyone is always so miserable and downtrodden. As for Dickensian Southwark… I just don’t understand the reference. Most of the area is very modern – post-Invasion. The Daleks did a lot of damage in that part of London and most of it has been rebuilt. I think there was a lot of resistance centred there and they took revenge by blowing most of it up.”

Sukie’s generation could talk openly about such things. For her parents who had been deeply involved in the resistance fight it was much harder. For Earl it all happened two centuries before his time, but he had talked to Sukie’s father and paternal grandfather about the Dalek occupation of Earth and he would never think of it as merely history.

“So we need to check out Dickensian London,” Earl concluded. “Long before the Daleks or even the twentieth century wars that messed up the city or the ‘regeneration’ of the twenty-first century.”

He set the time controls of his car to the mid-Victorian era when Dickens was the most popular living author.

Croydon airport in 1934 was beautiful. The neo-classical booking hall and arrivals terminal, the departure lounge, were all big, bright and airy rooms with a domed glass roof above the central area and lots of tall windows letting in natural light. There was almost a cathedral feel to the booking hall, except it was far noisier and the nearest thing to an altar was the appropriately named ‘time zone tower’ with clocks showing different times across the world on all sides.

“That would be a fabulous design for a TARDIS time rotor column,” Vicki remarked as she looked at it. “I should mention it to Davie as an idea.”

“It looks a bit TOO retro to me,” Jimmy answered her. “And a lot of people in our time would struggle with analogue clocks. Even when I WAS paying attention at school we only ever learnt to tell the time from digital displays.”

That was something he had learnt from travelling back in time with Vicki to eras when the very idea of a clock without hands turning around the twelve hours was unthinkable. He had probably also learnt the word ‘analogue’ somewhere along the way to describe that sort of clock. He couldn’t remember it being in his vocabulary before he started spending quality time with Vicki.

“What I don’t really understand,” he added. “Is how we’re supposed to meet a flight from Berlin, unless WE got the analogue time wrong. It’s one o’clock in the afternoon and the only plane due in from Germany is coming from Munich, not Berlin, and not until nearly nine o’clock. We missed today’s flight from Berlin at eleven o’clock this morning.”

“Yes, I’m wondering about that, too,” Vicki admitted. “But we followed the time and date exactly as it said. I expected us to be about an hour early.”

“Well, let’s have a look around, anyway,” Jimmy suggested. “I’d like to see the planes close up. Do you think we’d be allowed?”

“I’ve got psychic paper. We can look like we’re allowed.”

Jimmy grinned and headed towards the exit onto the concrete apron behind the terminal building where ground crew fuelled and checked the planes before passengers boarded them. The psychic paper allowed them through the ‘authorised personnel’ door so that they could get as close to the planes as possible.

Jimmy was thrilled. He pointed out the differences between several types of propeller, spoke eloquently about Rolls Royce engines and manufacturers like Mitchell, Avro, Armstrong Whitworth and others that Vicki stopped paying attention to after a while.

“I’m glad there aren’t this many different makers of TARDIS,” she said. “Between you and planes and Sukie with her car obsession all I ever hear about is engines.”

Jimmy laughed and put his arm around her shoulders, promising to look and not talk for a while.

“’You won’t be able to help yourself,” Vicki told him, but she didn’t mind. If she chose, she could talk at length about the properties of temporal physics. She was almost as skilled a TARDIS pilot as either Davie or Chris, now, and one day perhaps she would be as good as her father.

Sukie and Earl were frustrated. Victorian Southwark was a dark, dismal place even well away from the depressing sight of the debtor’s prison. The streets were narrow, cobbled and grey, with very small patches of sky above and not a lot of sunlight.

And apart from looking like the homes of the downtrodden that Sukie disliked so much in the works of Dickens they really couldn’t find anything that looked as if it was Dickensian.

“Dickens is still alive in this time,” Earl said, trying to think of a solution to their problem. “What if we find him and ask him about Southwark?”

“He doesn’t live in London. He has a house on the Kent coast,” Sukie answered him. “Broadstairs. I saw it once on a school trip. I don’t think that’s the connection. I think….”

She sighed and reached into her pocket for her mobile phone. Earl glanced around and pressed her into the doorway of a shabby, closed down factory before anyone noticed the future technology.

“What are you doing?” he whispered.

“Phoning my mum. She DOES like Dickens, and she’s lived in London for a long time.”

“Can we do that?” Earl asked. Then he thought about it a little more and realised there was absolutely no reason why not. It was still research.

“Mum,” Sukie said when the call was answered across nearly five hundred years of time and a few miles distance. “We’re doing the Mornington Crescent Quest, and we’re a bit stuck. Can you help?”

“Isn’t that cheating, sweetheart?” Susan answered.

“No. Mr Sweetwell said there ARE no rules. Besides, I don’t want the answer, just a bit of information. What is it with Charles Dickens and Southwark?”

“He lived there for a little while,” Susan answered straight away. “When he was a boy, his father was in financial trouble and ended up in Marshelsea debtors prison. Dickens and his sister lodged nearby until the family were re-united. He used the prison in his book Little Dorrit, and the Pickwick Papers uses a lot of the locations in The Borough. When I was at Coal Hill School Miss Barnes, the English teacher, took us all on a walk around the streets named after Dickens characters. I remember a Quilp Street and Copperfield Street, Little Dorrit Court, Pepper Street… Sawyer Road….”

Susan’s memory of school days nearly fifty years ago in her own lifetime and more than two hundred in real time petered out.

“Oh yes, and Doyce Street,” she remembered when Sukie pressed her again. “Daniel Doyce. He’s from Little Dorrit, too. And the street… more of a backstreet, really. It’s probably not on the maps, as such, if it’s even THERE at all in our time.”

“But you know where it USED to be?”

“In 1963 it was behind the beautiful old Welsh Congregational Chapel on Southwark Bridge Road. My school choir sang there once. We were all lined up at the back door and there was this funny old sign – probably as old as Dickens. It said ‘Commit No Nuisance’. We all laughed at it, but the choirmaster said it was very appropriate.”

“Mum, I love you,” Sukie told her mother, holding back her excitement. “That’s PERFECT. Thanks.”

“I still think its cheating, but I think you might know slightly more about Dickens than you did five minutes ago. If you’d READ his books instead of just watching the films.”

“I just never really liked his style,” Sukie answered. “Anyway, we’ve got to go. Love you lots. Give dad a hug for me. And tell Davie and Chris I’m going to beat their record in the Quest.”

“Just come home in one piece, that’s all I ask any of you to do,” Susan reminded her daughter before the call was closed. Sukie turned to Earl and grinned. He was already programming the time circuits for 1963.

“Don’t pick the day when mum’s school choir were there,” Sukie reminded him. “That would be a bit too much.”

Vicki’s interest wandered from the mechanics of powered flight to the preparations that a ground crew was making at a private hanger east of the main landing strip. While Jimmy admired a single seater twin-prop undergoing repairs to its undercarriage, she asked more pertinent questions.

“I think I know why we’re here,” she said proudly. “The plane due to land here in about five minutes is coming from Berlin, and it’s got a real VIP on board. Well, actually he’s kind of out of favour at the moment. He’s fallen out with the government over a couple of issues. I remember daddy talking about it. He said he was dead right to tell everyone in Britain to be wary of the Nazi party, but dead wrong about opposing Indian independence.”

“Who was that important whether he was popular or not?” Jimmy asked. Vicki smiled enigmatically. He liked that smile and was prepared to wait the five minutes until a silver and blue bi-plane came into view, circled the runway once and landed smoothly.

“It’s a de Havilland,” Jimmy enthused. “A De Havilland Rapide, I think.”

“Very probably,” Vicki responded. She watched as the small plane, carrying up to five passengers, taxied towards the hangar. She was a little worried when she saw three people get out of the passenger doorway who didn’t look at all important – just secretaries and aides. Then the pilot climbed down and she laughed as she remembered that the famous man had learnt to fly in the 1910s, almost crashing a couple of times before he actually got good at it. She grasped Jimmy’s hand before stepping forward.

“Mr Churchill,” she called out. “Hello, do you remember me? I’m Vicki, The Doctor’s daughter. I came to tea at your house when I was four.”

“Vicki?” Winston Churchill looked at the petite girl on the cusp of being a woman and tried to equate the maths. He was sure it hadn’t been that many years since he entertained The Doctor and his wife and their lively little child. It must have been, he decided. He reached out hand to shake with her and her young man.

“It’s very nice to meet you, again,” Vicki said politely. Jimmy was rotten at history in school, but he was suffering from an acute attack of nerves on meeting a famous person from the past and had trouble saying anything. He left it entirely to her. “Did you have a nice journey, sir?”

“It was uneventful,” he responded a little gruffly. “Which is more than could be said for my stay in Germany. Why can’t people here see how dangerous that ridiculous looking little man is? We ought to be preparing to defend our shores from his empire building mentality.”

“My father agrees with you, sir,” Vicki told him.

“That goes without saying, young lady,” Churchill answered. “Your father is a very intelligent man. But I seem to be surrounded by nincompoops – and worse – appeasers. There will be no appeasing Adolf Hitler, mark my words.”

He seemed to remember, then, that he was talking to a girl, not a political rally. He smiled what he thought was a warm smile, but perhaps didn’t quite come off. He reached into the inside pocket of his coat and took out a publicity photograph of the Chancellor of Germany.

“Some fool gave me this,” he said. He took a pen from his breast pocket and wrote on the back. “Have it as a souvenir, my dear. And in the years to come, show it to those people who thought I was talking nonsense.” He looked at Jimmy and shook his head. “I’ll take no satisfaction in being proved right. Not when it will be young men like you who have to bear the burden for those of us too old to do more than talk this time around.”

Jimmy thought of saying something about coming from a future when there was no impending war, but he couldn’t find the words. He murmured his thanks and left it at that.

“I must be off now,” Churchill said. “But it was very nice to meet you both. My regards to The Doctor. I expect I shall see him again in the future – him and his blue box.”

Vicki was so surprised by that remark that Churchill had reached the car waiting on the apron for him before he glanced down at the photograph in her hand. She noticed that somebody had used a fountain pen to draw devils horns on the head of Adolf Hitler at some point on the flight from Berlin. She turned it over and read the message on the back. The first two lines reminded people in the future that he was right about Hitler, but there was something more.

“No!” she exclaimed. “No, that’s impossible. How could HE have been involved in this thing? How could he have KNOWN?”

Jimmy took the photograph and read the next clue, written in Winston Churchill’s own handwriting and signed by the man himself beneath.

“I hope we can have this back after we present our souvenirs to Lord Sweetwell,” he said. “This is priceless.”

The time car brought Earl and Sukie to Southwark in 1963. It still looked a little grey in a real pea-souper of an evening fog, but it didn’t feel quite so oppressive as it did in 1863.

“That IS a very nice looking church,” Earl said as they looked at the brown and white front of The Borough Welsh Baptist Chapel. From inside came the sound of a choir singing ‘Bread of Heaven’ which went with the Welsh part, at least. The pleasant sound was in their ears as they went around the corner and reached the back of the chapel. Like many old buildings the rear was less well-adorned than the front, but there was a long arched window through which a warm light penetrated the fog and made them feel that they weren’t completely alone.

“There’s the sign,” Sukie announced, pointing to a white painted square of either wood or metal fixed part way up the chapel wall. ‘Commit no Nuisance’ was printed in bold black letters.

“We’re not going to commit a nuisance,” Earl promised. “But we ARE borrowing the sign for a little while.”

“I think that WOULD be classed as a nuisance,” Sukie pointed out, but she kept watch as Earl used his sonic screwdriver to loosen the screws holding the sign in place. He caught it as it fell and tucked it under his coat before they made their escape from the scene.

A few minutes later a policeman came by on his route through the backstreets. His torch penetrated the fog for a few feet in front of him. The beam picked out four screws lying on the pavement. He swung the torchlight up and around the wall and noticed that the sign was missing. He wrote the fact in his notebook. It wasn’t the first time it had happened. It always came back as mysteriously as it disappeared. He and his colleagues at The Borough police station had debated whether taking the sign constituted a nuisance in itself, but unless they caught whoever kept doing it, they really couldn’t make a case either way.

“Pick a paper rose when Green Park is grooving,” Vicki read on the back of the photograph of Adolf Hitler.

“Pick a paper rose in grooving Green Park,” Sukie read, etched into the back of the sign urging people to ‘Commit No Nuisance’.

“I don’t get it,” Jimmy commented.

“I don’t get it,” Earl said.

“Wow!” Vicki exclaimed in surprise as she felt the telepathic echo across time and just a few miles of space. “Did you feel that? No, you probably didn’t. Wait… I need a quick word with Sukie.”

Jimmy watched in bemusement as Vicki closed her eyes and put her fingers against her own temples. It wasn’t strictly necessary to make psychic contact with somebody she had always had such a close relationship with all her life, but it helped her to block out any outside influences.

Actually, it helped stop Jimmy asking questions if he thought she was doing something ‘alien-ey’.

“It’s a huge coincidence,” she said as she finished her ‘psychic phone call’. “Sukie and Earl have the same clue. We’re going to meet up with them and work together on this one.”

“Ok,” Jimmy agreed. “It’ll be interesting to see how they’ve been getting on.

Vicki was still partially in contact with Sukie. She programmed her TARDIS to look for her psychic ident and the vortex imprint of Earl’s time car.

The TARDIS found them in 1963 having a high tea at the Southwark high road branch of the ABC restaurant. Vicki and Jimmy had a cup of tea with them while they discussed the clue they all had to pursue next.

“Green Park is obvious.” Everyone agreed with Jimmy’s summing up of that part of the clue. “Even a dumbo like me knows the names of the Royal Parks of London. But the problem is when we’re supposed to be there. How do we pick the right day?”

That was the problem they were all puzzling over.

“Sukie,” Earl commented. “Why are you and Vicki BOTH singing a song in your heads about ‘your irritating love for me.’ I’m starting to feel a bit misunderstood.”

Jimmy looked puzzled by the lyric as said by Earl. The two girls burst out laughing.

“It’s IMITATION love,” they explained.

“That doesn’t sound much better,” Earl complained.

“We BOTH thought of it when the clue mentioned Paper Roses,” Vicki continued. “We used to sing it in the school choir. Mr Wilkinson said it was an old English folk song, but Grandma Jackie said it was a country and western song from America from when she was a girl – in the 1970s.”

“Paper Roses, Paper Roses,” the two of them sang out loud. “How real those roses seem to be - but they’re only, imitation - like your imitation love for me.”

“It’s not a very nice story, really. The woman is complaining that her man doesn’t really love her, and he just buys flowers and presents without meaning anything by it.”

“That’s a warning to us, both, Jimmy,” Earl said with a grin. “Don’t ever take these two for granted, or it will be IRRITATING LOVE.”

“I wouldn’t dare,” Jimmy answered. “By the way, exactly WHEN in the 1970s was that song about, because I’m wondering if it is a bit of a clue. This word ‘grooving’. The only person I ever heard use it is Trudi – and she’s from the 1970s.”

“I think you have a point there, Jimmy,” Earl told him. “Who has their phone under the table? Check out that song.”

“It was first recorded in 1960,” Sukie answered. “But it was a hit in the summer of 1973 by Marie Osmond.”

“I think that’s the version that Grandma Jackie meant,” Vicki confirmed. “And 1973 is around about Trudi’s time. That narrows things down. I think we should leave the rest to the TARDIS. It’ll see us right.”

She was right. The TARDIS brought them to a warm Sunday afternoon in the August of 1973. Green Park was buzzing with picnickers and sunbathers. The sounds from dozens of portable radios could be heard all over the park, most of them playing different tunes, but all of them the sort of laid back Sunday afternoon music that could be described as ‘grooving’.

“It’s nice,” Vicki commented. “Everyone so happy and relaxed. So many people enjoying themselves. Let’s get ice creams from that van.”

“We ought to see about these paper roses, first,” Earl suggested. “We still need to crack that bit.”

“I think I see what it’s all about,” Sukie responded. “Look.”

One of the very few people who was here alone in the park was a girl dressed in flowing, hippy clothes and a bandana around her head. She was sitting on a bench with a huge basket at her feet while she crafted something colourful in her hands. A closer look showed that she was making paper roses with coloured tissue, a little glue and a short piece of stick. A handwritten sign indicated that they were ten pence each.

“You two choose,” Jimmy said to the two girls. It’s not really a male thing.”

They chose and gave the girl twenty pence in the decimal coins that had come into use in recent years. She wished them a peaceful day and they walked away towards the ice cream van.

“Here’s the clue,” Sukie told Earl, holding the paper rose sideways by the very end of the stick and reading the very tiny lettering etched into the lightweight wood.

“We’ve got one, too,” Vicki said to Jimmy, but he wasn’t there. He had walked back to the flower girl and was examining the made flowers and the sticks in a little pile by her side. He came back to them very puzzled.

“There are no messages on any of the other sticks, and that girl thinks I’m mad.”

“We were ALL wondering,” Vicki admitted. “It must be some kind of trick, but I don’t know how it’s done at all. Never mind. Let’s get those ice creams.”

They got ice creams. They sat on the grass and ate them together, talking over their adventure so far. Sukie and Earl listened in amazement and admiration to Vicki’s recounting of their meeting with Winston Churchill and wondered how he had become a part of the Mornington Crescent Quest.

“Have you looked around at some of the people here, right now?” Sukie asked as she contemplated a second round of ice creams, not because of greed, but because it was so very warm. “We’re not the only ones who had the same clue. I think just about ALL the Questers are here. Look at that lot sitting in a little huddle. It’s the Vinvocci team. And the Vocci is over there, just keeping his distance.”

At first glance, of course, they looked like Human picnickers, but once it was pointed out it was obvious. Jimmy laughed at the absurdity of people with green spiky heads and hands eating ice cream cones in a Royal Park of London, even more so the red-spiky headed dwarf.

“The couple in the pink pinstripes almost look right here, with everyone in different coloured clothes,” Vicki noted. “They’ve taken off their jackets and they have pink shirts underneath!”

“Utterly Bohemian,” Earl remarked. “It must have been intentional, bringing us all to one place. I wonder if there’s some special reason?”

“If there is, they should be able to tell us,” Sukie answered, pointing out two women wearing gold hotpants and crop tops and lots of gold in their hair. “They’re Lord Sweetwell’s helpers, aren’t they?”

“I don’t think gold is a good colour for this weather,” Jimmy remarked. “I can hardly see them for the way the sun reflects off their clothes.”

“It must be hot in gold lamé, too,” the girls agreed. “It was nice wearing gowns with gold thread through them at Christmas in Samlesbury, but that’s just way over the top.”

The two women approached their group smiling.

“Greetings, questers. Lord Sweetwell thought you should all have a little break from the quest and enjoy the sunshine. That is why all of you were brought to this spot at this time. Please feel free to mingle and meet the other questers in a neutral place. The competition should begin again after sundown.”

“Thank you,” Sukie and Vicki said on behalf of the others. As the ladies moved on they noticed something remarkable happen. The Vinvocci and the Vocci joined into one group, talking together. The pink couple, Sen and Senata Dooli moved over to be with them. The four young time travellers looked at each other and then strolled towards the growing group of questers and sat down – all but Earl who went to buy ice lollies for everyone. By the time he returned with a whole polystyrene cool box of multi-flavoured rocket lollies for everyone the group had been swelled by the addition of the tall blue people they had first seen on Mornington Crescent station, Zinoop Gell, the four-eyed dwarf, and the man with the brolly on his head.

“Wait a minute,” Vicki said, grabbing a lolly and heading towards a solitary figure slouching along the path, crying sorrowfully. It was, beneath his perception filter, Sanoop the really stupid squid. Vicki offered him the ice lolly, which he took gratefully and swallowed in a single gulp. She brought him to the group of questers and gave him another lolly – and another.

“He’s suffering from heat exhaustion,” Vicki explained. “Hot, sunny weather isn’t good for his amphibious species. He really needs to be somewhere damp and cool.”

“Here,” said the man with the brolly, and placed it on Sanoop’s head, giving him some shade. The blue couple brought a thick, blue-tinted tub of sunscreen from their bag and liberally applied it to all of Sanoop’s exposed flesh. The Vinvocci pair gave him a backpack full of lemonade with a drinking tube.

“There’s a rock garden in the north end of the park,” said Zinoop Gell. “When we’re done with the ice lollies I’ll take him there. He can cool off in the shade for a bit.”

Sanoop tearfully thanked everyone for their kindness and admitted that he was doing very badly in the quest. He had LOST the souvenirs of his first two quests, a bar of soap from the public rest rooms of the Houses of Parliament and the telescope from Nelson’s statue in Trafalgar Square.

“That’ll turn up sooner or later,” Earl said. “Things of any importance always do. The soap doesn’t really matter. Do you have your paper rose? At least you can carry on with the last two quests. It’s about taking part as much as winning.”

Sanoop held up his rose. It fell apart in a soggy mess. He had been holding it in the same hand as his ice lolly. Jimmy took his stick and tried to read it, but it was ruined.

“I think you should come along with me,” said Zinoop Gell. “We’ll be a team from here on. It’s more fun with a partner, anyway.”

Sanoop started crying again, out of gratitude. Vicki gave him a handkerchief and urged him to keep it. After several blows of his squid nose it was covered in ink coloured mucus. She really didn’t want it back. Even as a tissue sample for a science experiment it was a bit too horrible.

“I never realised that it WAS so much about getting to know each other as different time travelling species as winning the competition,” Sukie noted. “Everyone in my family has competed except my dad and his dad, and they ALL talked about how close they came to winning. But it SHOULD be about making friends, too.”

She glanced at the Vinvocci and Vocci. It was probably the first time any individuals of that race had sat so close together in ten generations, let alone talked to each other as they were doing now. She hoped it would last beyond the competition. As for the pink-pin-stripe couple, Sen and Senata Dooli, she really liked them very much and had asked them to come to tea in the twenty-third century some time. She would have to explain it to her mum, but she was sure there would be no problem, there.

The mysterious and apparently priceless prize for winning the competition didn’t seem at all important somehow compared to the friendships that were forming here under the summer sun with a box of ice lollies to share between them all.

If the feeling would remain after sundown when the quest began again in earnest it would be very special, indeed.

|

|

|