By mutual agreement, the two teams from twenty-fourth century London didn’t reveal their clues to each other or talk about their future tasks during the ‘truce’ on Green Park. Only when they were back in their respective time machines did they discuss their next quest with their team-mates.

“Take the bacon from Surrey Docks,” Sukie read to Earl then looked at him quizzically. “Are we supposed to raid a ship bringing in goods or something?”

“I don’t think they landed livestock at Surrey Docks,” Earl responded. “Wouldn’t that be done closer to the main meat market. What was it, now, Billingsgate?”

“No, that was fish,” Sukie answered him. “Meat would be Smithfield. Fruit and veg at Covent Garden. Smithfield is right in the City of London, near all the stockmarkets, and it’s on the other side of the river, too. The docks for unloading that kind of thing would be in a completely different place.”

“So what does bacon have to do with anything around Surrey Docks?” Earl wondered aloud. He tapped on his mini-computer screen and brought up a map of the area in his own time and overlaid it with maps from various earlier times trying to find some clue. “Maybe it’s not meant to be literal. Perhaps there’s a Pig Lane around there… or something.”

“Oh… no. We’re idiots.” Sukie was still holding the paper rose. She pushed the paper leaves beneath the bloom up a little further and it revealed another word. “Look up Surrey Docks FARM.”

“Why would there be a farm in the middle of London?” Earl asked. That made even less sense to him, but at least bacon and farms had some connection.

“I have no idea, but that is the end of the sentence. There’s a very tiny full stop there. We didn’t read it properly before. We were trying to be too clever.”

“There IS a place called Surrey Docks Farm,” Earl confirmed. “Or there will be in 1975.” He looked out of the windscreen of his disguised time car at London in 1973, the summer of the paper roses and sunshine that was a brief respite from a darker reality of industrial unrest and IRA bombs. “It lasted until 2085, when the land was finally taken over for offices.”

“Ok, so are we expected to go there and buy a pig?” Sukie asked. “A live one… or….” She wrinkled her nose in a way that Earl rather liked, but was actually an expression of disgust. “Please tell me they don’t slaughter the animals there. I am NOT going to pick out a pig to be turned into bacon. I won’t do that. I know it IS how we get meat, but I don’t want to be THAT closely involved in the process. I prefer bacon to be packaged in shrink wrap so that I don’t have to think about where it came from.”

“No,” Earl said, looking at some images of the inner city farm where children were invited to visit and find out where milk came from before it was sealed in tetrapacks and sold in the supermarket. He closed the page before Sukie could see and smiled at the small secret he had discovered. He would surprise her with it.

I think the mid-2010s,” he said. “That’ll be about right.”

“By hook or by crook, borrow the policeman's coat from Great Newport Street,” Jimmy read aloud.

“WHAT?” Vicki looked at him across the TARDIS console. “Honestly, does Lord Sweetwell make these up himself? That is SO cryptic.”

“Borrow a policeman’s coat? I’m not sure I’m up for that. I mean… ‘ borrow’ usually means ‘steal’ in these clues. Policemen don’t really go for that.”

“Yes, I’m a bit worried about that,” Vicki admitted. “At least Great Newport Street is easy enough.” She confirmed the location on the interactive maps in her TARDIS database. “It’s near Leicester Square. Ohhh, let’s go there in the 1980s. Leicester Square used to be where the London premieres of all the big films happened. It’s so atmospheric. All the lights and the crowds, and traffic, and yet thousands of starlings would be singing in the trees in the middle of the square.”

“You mean you want to go and see a film?” Jimmy wondered. “Weren’t they kind of boring in those days, before we had three-dimensional holovids.”

“Actually, I love watching old-fashioned two-dimensional films,” Vicki admitted. “Daddy took us to see the premiere of a film called Back To The Future in 1985. Sukie and I, and her two brothers went. He said it was the best way of showing us the dangers of interfering with a Fixed Point in Time without getting all serious and boring about it.”

“And was it?” Jimmy asked, his interest piqued even though this was yet another story about things Vicki had done with her ‘daddy’. Since he had never done much with his father except take blows from him when he was in a bad mood, he always found the perfect relationship she had with The Doctor just a little bit annoying. It wasn’t Vicki’s fault, and he would never let her know he felt that way, but he truly envied her all those experiences.

“Yes, it was, actually,” she admitted. “For something thought up by humans for entertainment it really did contain a lot of serious lessons about time travel. But to get back to your other question, I don’t think we have TIME to see a film. We have to crack on with the Quest. But we COULD go and soak up the atmosphere in the Square before finding out about Great Newport Street and policeman’s coats.”

“We can’t go anywhere near the premiere of that film you were talking about,” Jimmy told her.

“Yes, I know,” Vicki answered. “THAT is exactly what Daddy was telling us by going to see it. I’ll pick another premiere night.”

Earl and Sukie followed a group of teenagers from a youth club who were seeing around the working farm with the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf business centre actually in the background, visible over the stables and barns and the modern dairy where the children of the capital actually got to see milk produced by a herd of cows.

“Surely they don’t REALLY think milk comes from a factory?” Sukie remarked as she observed the astonishment on the faces of some of the teenagers. “I mean, even if they DO live in Tower Hamlets or Peckham, surely they have books and television.”

She noted just how many of the youngsters of her own age group had turned from the milking demonstration to note down the experience on their smart phones.

“Surely there is an APP for it,” she added with just a little hint of sarcasm. She had never quite understood the trend in this era of Earth’s history for walking around looking at a three inch screen. She was only surprised that more people in the early twenty-first century didn’t fall over or walk in front of traffic while they were so engrossed in the ‘social media’.

Earl laughed and pointed out that they spent quite a lot of time emailing each other when they were living in their separate centuries. Sukie insisted that was different and asked where the pigs were.

“The sties are over there,” Earl answered her. “But since you don’t like getting up close and personal with future pork chops I thought we’d get on with the task we came here for.”

He actually led her out of the farm complex and onto the footpath that ran alongside the stretch of the Thames known as ‘Rotherhithe Beach’. All along the path were surprisingly lifelike sculptures of farm animals. Sukie reached out to touch the model of a goat that strongly resembled one that had tried to eat her shoulder bag earlier. A donkey stood proudly next to the fence further on, and a family of geese were frozen in mid-waddle while an urban fox kept a furtive eye on them.

Finally they came across the pigs – a ‘mother and father’ escorting a trio of piglets, all of them with the kind of engaging expression of their snouty faces that would make the most hardened carnivore swear off sausages.

“They remind me of some of the families of humans going around the farm,” Sukie commented with a giggle. “The piglets are snuffling around and totally ignoring the parents, just like all those kids with their eyes fixed on their Twitter feeds.”

“I’m going to take the smallest of them,” Earl said, pulling his sonic screwdriver from his pocket. “Don’t get all sentimental about me breaking up the family. They’re made of cast iron, and besides, it’ll be back later with no harm done!”

He used the laser mode to cut just beneath the smallest piglet’s trotters where they were welded to the ground. For all that he had teased Sukie about being sentimental, he was very careful not to cut through the legs of the statue and to bring it away whole.

“I feel really conspicuous like this,” he admitted as he wrapped his jacket around the iron piglet to disguise his act of casual theft. “Let’s get back to the car quickly, now.”

It was early evening in December 1988. The film being given a royal premiere at the Odeon, Leicester Square, was called Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Vicki thought it looked like a fun film, but they had already decided they didn’t have time to go to the cinema, only to enjoy the atmosphere of the Square on a premiere night before going to find Great Newport Street not so very far away.

The bright heartland of London as an entertainment and shopping capitol was enchanting on this crisp, cold but not bitter evening. The streets were decorated for Christmas and even though it was rapidly getting dark there were plenty of people around.

Great Newport Street was no exception. It was busy with pedestrians and traffic. Vicki and Jimmy held tight to each other determinedly and tried to look carefully around a street where everyone else was hurrying by to get to the next shop before closing time.

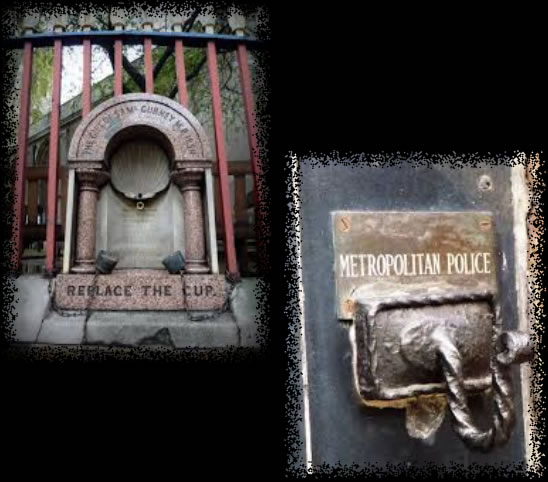

“We’ve come in the wrong time,” Jimmy said eventually. He pointed to something that might easily be missed in the crowded street. It was a quite innocuous thing nestled in the corner between a ‘trendy’ pub and an art gallery with a blue plaque declaring it to be the former home of the artist Joshua Reynalds.

It was nothing more than an iron coat hook with the words ‘Metropolitan Police’ stencilled into the metal backplate. That was where the clue had led them.

“For the policeman on traffic duty to hang up his cloak,” Vicki guessed. She looked around. “There isn’t a policeman now. There are traffic lights. Besides, I’ve been to this era a lot. Even a policeman wouldn’t dare leave a coat here without it being stolen. It’s not a terribly honest time.”

“It’s not the hook we’re here for, then?” Jimmy queried. That would have been simple enough, even in the crowded street. “We’ve got to go back in time and steal a policeman’s coat?”

“Yes,” Vicki confirmed.

“When exactly?” Jimmy asked.

“Before traffic lights but AFTER the establishment of the Metropolitan Police,” Vicki summarised. “Maybe the 1930s. Traffic would be busy enough by then to keep a policeman occupied.”

“Yes but….”

It was one of those mysteries, again. Somehow a clue would be on or in this policeman’s coat, but how many policemen, on how many days from the mid-Victorian era to the 1950s or so when the traffic lights began to be used, must have hung their coat up here?

Not when it was cold or raining, perhaps. But on a warm, spring afternoon when the cloak was superfluous?

That still left a lot of days to choose from. Jimmy didn’t know how they were supposed to find the right one. Neither did Vicki. She trusted the strange ‘magic’ of the Quest and her TARDIS’s sense of direction.

They arrived in the mid-1930s when the blue box actually fitted quite congruously at the top end of Great Newport Street. The policeman on duty at the bottom end where it was part of a complicated junction of five different roads would have thought it quite normal and unsurprising.

The art gallery that used to be the home of a great artist was just a solicitors office in this time. There was no blue plaque there, yet. That trend for marking historical sites didn’t begin until later in the century. The trendy pub was a much more discreet place called The Cranbourn. A small theatre and a large haberdashery, a bookshop and more offices for solicitors, charted accountants and surveyors completed the busy but dignified street.

The policeman was standing on a small island next to a lamppost. He was right in the middle of the traffic coming from every cardinal point of the compass, managing the cars, vans and buses and older, horse-drawn vehicles expertly with a series of hand signals and waves.

Vicki and Jimmy walked up and down the street four times trying to work out the best way to carry out their act of larceny.

“Ask him the time,” Jimmy said to his girlfriend. “Or the way to the station – something like that. Put on your sweetest smile and charm him.”

“I don’t….” Vicki began. But everybody knew that she did. It wasn’t deliberate, but she had a smile, partly from her mother, but mostly from her father’s side of the family, that could melt the hardest heart and distract men from their purpose. It mostly only worked on humans, of course. Other races that looked for other characteristics in their females weren’t quite so enchanted.

Her father always said, to the puzzlement of everyone in her twenty-third century family, that she had ‘The Baby-Spice Factor’.

She crossed over to the traffic island casually while Jimmy, equally casually, strolled along the pavement. The policeman carried on directing traffic while, at the same time, answering her question with a whole separate set of signals and waves of his arm.

Jimmy reached out and took the black cloak off the hook, folding it under his arm as he kept walking towards the TARDIS. He didn’t run, attracting attention. He didn’t try to hide the policeman’s coat under his own. He just kept walking as if he had a perfect right to be doing so.

And nobody noticed. Nobody called out or attracted the policeman’s attention.

Vicki got back to the TARDIS a few minutes later. She looked at the cloak laid across the railing and shook her head sadly.

“It seems rather mean,” she admitted. “He was so very nice. I asked him the way to the post office and he directed me without once getting his traffic signals mixed up. I hope the cloak gets put back before he misses it. I feel quite bad about it all.”

“I don’t think we need to take the whole cloak,” Jimmy told her. “I found the clue. It’s on the label inside. We could cut that off and then put the cloak back where it belongs. I don’t mind walking up the road again if you keep the door open for me coming back.”

Vicki found a small pair of scissors and cut the maker’s label and size out of the cloak, placing it safely in her purse along with the ticket from the Alexandra Trust Dining Rooms. Jimmy tucked the cloak under his arm again and walked out of the TARDIS.

Vicki watched him saunter down the road. She saw him hang the cloak back on the peg. It was only THEN, that somebody noticed what he was doing and shouted. The policeman looked around and halted all of the traffic as he ran across the road, but by then Jimmy had knocked down two pedestrians who tried to stop him and leapt in front of a double-decker London bus before he ran, head down, straight for the open door of the TARDIS. Vicki slammed it shut behind him as the very nice policeman came running up, blowing his whistle. Inside, the two young time travellers watched on the view-screen as he assured a group of onlookers that the would-be thief was trapped, and that his colleagues would be along presently to make the arrest. He told a young paper boy in a flat cap to keep a ‘weather eye’ on the box while he got back to his traffic.

“Oh, dear,” Vicki said. “This is going to upset them.” As the policeman resumed his place among the now heavy traffic she went to dematerialise the TARDIS. She could only imagine the astonishment of the onlookers and the puzzlement of the policeman and his colleagues about the thief’s peculiar escape.

“It’s not fair, really,” Jimmy said as Vicki parked the TARDIS in temporal orbit over London and they turned their thoughts to the next clue. “I WASN’T stealing it, I was putting it back.”

Earl found the next clue embossed on the underside of the piglet. How long it had been there, and why nobody else had ever seen it he couldn’t begin to guess.

“Bring the apple and serpent of sin from Petty France.” He frowned. “Little France? In London?”

“It’s a street,” Sukie answered. “But I don’t get the rest of the clue. I suppose we’ll find out when we get there. “It sounds as if we have to do some more stealing, though. I really don’t like some of the things we have to do for this quest.”

“Take a cup of pure, clean water from the first drinking fountain in London.”

“Take a cup of water?” Jimmy made an exasperated sigh. “What will they think of next? Do we lose points for spilling any?”

“I don’t know,” Vicki answed. “But I DO know that drinking fountains were very important in Victorian London. After it was discovered that cholera was caused by dirty water, a lot of old pumps were closed down and new fountains were built that took clean water from a new reservoir. They had cups attached to little chains so that anybody could get a drink when they wanted.”

“And they didn’t worry about germs on the cup?” Jimmy asked.

“I suppose not.” Vicki thought about that for a little while. “Perhaps somebody came along and washed them from time to time. Anyway, I KNOW that the very first fountain, and quite a lot of others are still around in our day, even if they don’t have water in them any more. They’re preserved as part of our history.”

That was one of the gaps in Jimmy’s knowledge.

“We went on a school trip once, in Miss Wright’s top junior class, and saw one of them in Regent’s Park.”

“I must have missed that,” he admitted.

“You were too busy trying to break the swings in the children’s playground with your gang,” Vicki answered. “It was in your not so nice days.”

“When I still lived with my dad,” Jimmy added, in defence of his behaviour when he was younger.

“Well, anyway,” Vicki added, moving on from those reminiscences. “The FIRST public drinking fountain is near Holborn Viaduct. Let’s go and see it when it was new. We can dress a bit nicer than we did for the Dining Room. Middle class people would use the fountains, too.”

The road called Petty France because Hugenot refugees from the purges of the eighteenth century had once settled there, was in the Borough of Westminster, running parallel with Birdcage Walk and St James’ Park. By the late twentieth century it was a genteel street of restaurants and specialty food shops with private accommodation above in the mostly early Victorian buildings.

Sukie and Earl found the apple and serpent easily enough. It was the symbol of a public house called The Adam and Eve. A plaque outside proclaimed it to be one of the oldest pubs in Westminster, dating from the 1660s when it was popular with members of parliament. Indeed, they spent so much time there that a bell was installed to be rung when they had to return to the House of Commons to take part in the important business of government.

“It would be easy enough to steal it,” Earl noted. “I could break the chains with the laser mode of my sonic screwdriver and catch it as it fell. We’d be gone before anybody noticed.”

“Yes,” Sukie observed.

“But I’m not sure I want to do it. First it was the weather vane from a church, then the piglet, now a pub sign. I draw the line, I really do. I’m not going to steal ANYTHING else. We’re going to have to think of some other way to complete this task.”

“I agree,” Sukie told him. “I mean, it IS just a pub sign. The weather vane was worst, because it belonged to a church, but I think you’re right. We’ve done enough vandalism.”

“So do we give up on the quest, tell Sweetwell that we’re not criminal enough for his game?”

“I don’t want to,” Sukie admitted. “I don’t like giving up on anything. We’re a family who don’t give up, after all. I don’t know. But I do know one thing. They do food in there. I can smell sausages and gravy among other things. Let’s go and eat and we’ll think about it.”

Earl was happy to comply with that suggestion. He pushed open the pub door and they entered into its warm, ambient environment.

“The fountain was built in 1859 by the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association,” Vicki explained, reading the information from the TARDIS database. Jimmy laughed. “Yes, I know it’s a fantastic name for an organisation.”

“I suppose they didn’t fancy using their initials, you know, like RSPCA.”

“MDFCTA is just as much of a mouthful. Anyway, as daddy often says, ‘it does what it says on the tin’.”

“The tin?” Jimmy was puzzled by the literal application of The Doctor’s axiom gleaned from late twentieth century culture, but Vicki just shrugged and continued to explain that the very first fountain that the grand organisation put in place was set into the railings of St. Sepulchure-without-Newgate Church in Holborn, and remained there all the way into their own twenty-third century where it was used as a planter for a floral display.

“Nobody would drink tap water in our time, of course,” Vicki admitted. “It is just as easy to get a cold drink in a hermetically sealed biodegradable bottle from the dispensers on the street corners. That’s our modern equivalent of the fountains. They’re not so pretty, though.”

“Seven thousand people a day USED the fountain?” Jimmy was astonished by the information Vicki had found. “Seven thousand? I can’t imagine that many people walking past one place in a single day. Could that be a mistake?”

“No, I don’t think so,” Vicki answered. She grabbed the cloak that went over her late Victorian dress and headed for the TARDIS door. Jimmy followed, wearing the clothes of a young gentleman of the era. He took her arm as they walked along Giltspur Street in the Holborn area of London. “You see, a lot of ordinary houses wouldn’t have a water supply of their own, and getting a drink of water in the street from what they knew was a safe source, with no cholera or other germs in it, was important. People wouldn’t just be walking past. They would come here especially for the water. Also, the Temperance Movement was encouraging people to use the fountains instead of going to pubs.”

Jimmy laughed again, but with a hollow edge to his laughter that time.

“The Temperance Movement didn’t understand about alcoholics. My dad wouldn’t have come for a drink of water rather than go to a pub.” He looked across the road to where there was, indeed, a public house doing plenty of business.

“You might be right about that,” Vicki conceded. “But look at that.”

They had come to the railings of the complexly named St Sepulchure-without-Newgate which simply meant that the church was just outside that particular city parish. The fountain was actually in use just now by a man and woman in the same sort of working clothes as the people who had eaten at the Alexander Trust Dining Rooms. A carter who had left his horse drinking from a trough further up the road waited for his own turn to drink.

Vicki and Jimmy joined the short queue and soon they had the opportunity to place the tin cups under the little tap within its cool stone alcove. They sipped the water. Jimmy noticed the different taste to the kind of water he was used to drinking in the twenty-third century. Vicki did, too, but she could also analyse the constituent parts of the water and confirm that it was as pure as anything that might be found in a great city like London.

“Replace The Cup.” Jimmy noted the message carved into the stone beneath the fountain. “But they want us to TAKE it.”

He looked at the bottom of the tin cup on a length of chain and saw letters embossed into it. The message they were looking for.

“No,” he said firmly. “I’m not going to do it. If this water is so important, I am NOT taking the cup. Vicki, you know how to do a brass rubbing. Make one of the bottom of the cup to get the message. I’m going to do something else about the water.”

Vicki did as he suggested very quickly before anyone else needed a drink, then waited until Jimmy returned from the TARDIS carrying a plastic drinking cup with a sealable top. He waited his turn again and filled the plastic cup with water from the fountain.

“THAT fulfils the Quest,” he said triumphantly. “And without stealing something important to ordinary people.”

“I agree,” Vicki told him. “And you know what else… I’m really proud of you for thinking of that.”

She would have kissed him, but that kind of thing wasn’t done in the streets in Victorian London.

Adam and Eve’s in Petty France had a long-held reputation for good pub food. The sausages that Sukie’s sensitive nose could detect among all the other smells of the pub kitchen were part of their popular ‘bangers and mash’ choice. The two young time travellers decided that was exactly what they wanted to eat and were served generous portions of creamy potatoes topped with fat, juicy sausages in gravy.

“Don’t make me think about those little pigs at Surrey Dock Farm until I’ve finished eating,” Sukie warned her boyfriend. “This looks too good to start thinking about where it came from.”

“I don’t intend to,” Earl replied. He sipped a glass of lager with his food. Sukie had lemonade shandy. They enjoyed their food after so much wandering around London doing thoroughly absurd things.

“I absolutely am NOT going to steal anything else, though,” Earl insisted again as they talked over the adventure so far. “The weather vane is sort of ‘borrowed’, but the piglet was pushing it.”

“I told you not to remind me of the pigs,” Sukie told him. She reached for a paper napkin to wipe her mouth after swallowing a particularly succulent piece of sausage and then stopped and looked at the square of absorbent paper carefully. Earl watched curiously as she held it up to the light and turned it around four times to look at each edge.

“You don’t have to steal anything else,” she said, finally. “The napkins are complimentary.”

She passed the now slightly crumpled napkin to him and he looked at it casually, trying not to look as if it was important.

The paper had the symbol of the apple and serpent as seen on the pub sign outside embossed into it, and around the very edges in very small writing was the last clue they were looking for.

He looked at his own napkin, then reached behind carefully and took one that another customer had left on his plate after finishing his meal.

“Only OUR napkins have the clue on,” he said. “HOW is it done, do you think? I don’t believe the waitress who brought our food was in on it, and we chose this table more or less at random.”

“I don’t think we’re supposed to know that,” Sukie answered. “Davie said it was probably something quantum, but he might have been teasing me, making out it was a complicated scientific thing that I’m not meant to understand when he didn’t know, either.”

“I’m not going to dispute either of your brothers,” Earl admitted. “They both scare the daylights out of me. They’re legends in my lifetime.”

Sukie giggled. Earl had won a grudging respect from Chris and Davie, but he still trod carefully in their presence.

“Anyway, what does the message say?” he added, recovering his composure as he put all thoughts of Sukie’s brothers from his mind.

“It says,” she answered. “Congratulations, you have completed the Mornington Crescent Quest. Bring your treasures to the station on the third morning, first come wins first prize.”

“So we’ve done it. We’ve just got to get back to the station.”

“Yes.”

“Good. There’s plenty of time for dessert and coffee before we have to head back there. I don’t know about you, but I like it here. Let’s enjoy it a bit longer.”

“Congratulations, you have completed the Mornington Crescent Quest. Bring your treasures to the station on the third morning, first come wins first prize.”

“That’s what was written on the bottom of the cup?” Jimmy queried.

“Yes. But it’s written in Alzerian, which just looks like random scratches to anyone who hasn’t travelled by TARDIS and can therefore translate Alzerian in their head.”

“Well, that’s good,” jimmy observed. “Otherwise people might be turning up at the station all the time. Do we go straight there, then?”

“We have an hour until the appointed time, when the gate is open,” Vicki answered. “Then it’s the first to get to the platform with all the souvenirs to present to Lord Sweetwell.”

“So it’s a sort of race to the finish?”

“Yes.”

“That could be dangerous, everyone rushing down those escalators at once. But I’m game for it.”

The TARDIS arrived at the traffic island where Richard Cobden’s statue watched over the street at the same time that Earl’s time car arrived and parked in a two hour waiting zone. The four young time travellers strolled together to the shuttered off entrance to Mornington Crescent station. Two of the other teams were waiting already. The tall blue couple were loaded down with a gold painted cast iron pineapple and a small bronze replica of St. Paul’s Cathedral among other things. Sanoop the squid and his teammate had a bronze spear taken from some classical statue in London. They had it concealed inside a long bag for carrying fishing tackle but the point of the spear was poking out and Zinoop had to keep apologising for accidentally pricking people with it.

“Hold it point down towards the floor,” Jimmy suggested. “Then you can’t hurt anyone. Did you get all of your souvenirs?”

“We did,” Zinoop announced. “Sanoop was quite helpful to me in the last quest. The clue was on a tile in the bottom of the fountain in Trafalgar Square. He held his breath long enough to prise it out and bring it to the surface while I distracted the police who might have prevented him from doing so.”

“Well done, Sanoop,” Vicki said. The grey-faced character beamed with pleasure at receiving praise instead of the usual censure. At last his only natural talent – for getting wet – had proved useful and he was a hero if only to Vicki.

The crowd was getting larger when the gate rose up slowly. The gap was only about a foot and the taller humans and humanoids were still getting ready to rush forward when Sanoop surprised everyone again by slithering under the gate. Of course, his body could flatten out like his ancestral squid race. Zinoop waited until there was another foot of space and ducked under. There were murmurs of disconcertion, but there was nothing in the rules about it, after all. The gate was open to short people first, and gained them a slight advantage.

Jimmy and Earl both grasped their girlfriends and gained a head start on the others even with some of their more cumbersome souvenirs – windvanes and piglets and all. But Sanoop and Zinoop were already ahead, riding the railing of the down escalator, carrying the spear at head height. They were clearly going to reach the platform first.

“Pipped at the post by a pair of pipsqueaks,” remarked Senata Dooli philosophically as the Questers gathered in the artificial light of the underground station platform.

“It’s the taking part that counts,” her husband acknowledged.

In fact, nobody seemed at all disappointed that Sanoop and Zinoop had clearly won. They applauded them when Lord Sweetwell emerged from his broom cupboard to present them with their prize.

“Seriously?” Jimmy queried as he watched the presentation. “Those purses contain an endless supply of money?”

“They contain whatever money is needed at any time – be it the price of a cup of tea or the deposit on a house,” Earl explained. “It is a priceless prize. It only works for the rightful owner of the purse, though. If it is stolen it will yield false coinage and get the thief into bigger trouble.”

“Still….” Jimmy sighed whistfully. “I wish….”

“Jimmy Forrester!” He was startled when Lord Sweetwell called his name. “Jimmy Forrester step forward and present your cup of water from the fountain at St. Sepulchure.”

He stepped forward in obedience to the command and presented the plastic cup with the seal preventing spillage. Lord Sweetwell took the lid off and tasted the water.

“Indeed, that is the water from the fountain placed by good men in bad times. But why did you not bring the cup that was attached to the fountain itself? Were you worried about spilling the water?”

“No,” Jimmy answered. “I was worried about people not being able to drink while it was missing. It was quite wrong to take that cup.”

“Indeed it was, my dear boy,” Lord Sweetwell answered him. “You are the first to realise that in all the years I have been setting that puzzle. The clue asked for a cup of water, not THE cup. You considered the needs of the people of London above the trivial requirements of my little game.”

“Yes, sir, I did,” Jimmy insisted.

“And in doing so, you won my special discretionary prize.” He nodded to one of his golden girls who stepped forward with a gold tray containing what looked like a very ordinary booklet with a deep mauve cover. Lord Sweetwell presented it to Jimmy who took it curiously, wondering what it could actually be.

“It’s… a bankbook,” he said, opening the cover. “From the… the Yorkshire Building Society.”

“Established in the year 1864 as a safe place for ordinary people to put their savings. in that very year two thousand pounds was deposited in an account. That two thousand pounds is yours, now, Jimmy Forrester.”

Two thousand pounds didn’t sound like a lot, but he turned to the page where the present balance was recorded and almost fainted in shock.

“Two thousand pounds deposited in 1864 and accruing compound interest until the twenty-third century,” Earl said. “That’s a nice little nest egg for you, Jimmy.”

Jimmy was temporarily speechless.

“It’s… enough to….”

It was enough to make that Bond of Intent for Vicki’s hand in marriage when the time came, enough to see him through university without needing government grants, enough to get him started on his career path and to put a deposit down on a modest but comfortable home when he and Vicki were ready to seal that Bond and settle down together

It wasn’t a bottomless purse, but it was more money than he ever expected to have in his name, and he was reeling with the news that he had been given it because of one small decision he made without any thought or expectation of any consequences for himself.

“Well done, Jimmy,” Vicki told him, grasping his hand tightly. “I’m proud of you.”

“I’m… a bit proud of myself,” he answered. “But I don’t have any money at all in my pocket right now. I think you’d better pay for coffee over the road at that café. That’ll bring me back down to Earth again with a bump.”

“They’re on me,” Earl assured him. “It’s not so long since Sukie and I had bangers and mash for supper, but I might even spring for bacon butties all round and call it breakfast.”

|

|

|