“Remind me again why we’re here,” Jimmy Forrester asked his girlfriend as the escalator descended into one of London’s underground stations in the early twenty-first century. Sukie and Earl were there, too. They were dressed in modern casual clothes for a change. The last few trips they had all taken were to times when period costume was required – meaning embarrassing ‘hose’ for the men.

“This is Mornington Crescent station,” Vicki explained. “We’re here to take part in the time traveller’s scavenger hunt named after it. We’re practically the only members of my family who haven’t done it, yet. Daddy has played at least twenty times, including once with mum and Captain Jack before I was born. Grandma Jackie and Christopher have done it. Chris and Davie have done it twice, once when they were teenagers with their first TARDIS, and last year competing against each other with Brenda and Carya as their teammates. Even Tristie and Trudi did it, with the baby along with them.”

Jimmy laughed. It was the only response to Vicki’s family tree which stretched to generations not yet born in their own time.

They reached the platform and he looked around at the assorted people waiting there. At first glance they seemed to be ordinary commuters – except that the station wasn’t actually open, yet.

On second glance, with the advantage of having travelled quite extensively by TARDIS and having thus absorbed some of the harmless background radiation from the vortex, he could see through the perception filters, invisibility cloaks and other glamours that disguised the true nature of many of the competitors in the Mornington Crescent Quest. Two couples were almost Human apart from having green skin and spikes coming out of their faces. A lone entrant was half their size and red but with the same spikes. It was Sukie who explained that the taller, green species were vinvocci and the smaller vocci, and that they hated each other.

“These individuals or their races as a whole?” Jimmy asked, noting that red and green were standing far apart and deliberately not looking at each other.

“The races,” Earl answered. “They’ve had a sort of ‘cold war’ going on for centuries. As long as they keep clear of each other it’s no problem for anyone else.”

There were some tall, slender blue people, too, and a man with two heads, side by side on very wide shoulders. Jimmy wondered if he counted as a team or an individual. Various numbers of eyes, shapes and orientation of noses and mouths also marked out some from the Human form normally seen on the platform – or, indeed, the planet.

Even some of the humans were not quite ‘normal’ as far as Jimmy knew normal to be. The tall man and short woman both wearing shocking pink pinstripe suits weren’t doing anything to be inconspicuous. Nor was the man wearing a bowler hat with a brolly attached to the top of it.

The buzz of conversation came to a sudden silence as a man wearing more diamond rings than he had fingers and a gold lamé jacket with a kipper tie of silver and gold held down by three diamond pins emerged from a door marked ‘staff only’. He was riding a solid gold invalid scooter and flanked by pretty blonde women wearing very short, very tight, gold and silver dresses and gold stars on their cheeks. They carried baskets of gold envelopes.

“He is Lord Arthur Sweetwell, the richest man in the fifty-first century,” Vicki explained to Jimmy. “He invented the Vortex Manipulator and then retired to… well goodness knows where. He seems to have lived in that cupboard for the past hundred years or so. Or maybe he lives in some kind of null space and comes out once a year to start the Quest.”

“Welcome to the 2016 Mornington Crescent Quest,” he said in a clear voice that rang around the enclosed space of the underground platform. “When I call out the team name or individual, come and get your envelope with your first clue. The winners are the first to return with all their souvenirs at five a.m., two days from now. Though time travel is the object of the exercise it must be in real time. Any cheating will be found out. You know it will, so don’t even try. Fair play between teams is expected, and no civilian is to be molested or harassed. Otherwise, anything goes.”

The left hand girl stepped close to the scooter and he took the first envelope, calling for Sen and Senata Dooli. The bright pink couple took their envelope. A dwarf with four eyes called Zinoop Gell was next, then a skinny humanoid with strangely glistening skin answered to the name of Sanoop.

“I’ve met him before,” Earl commented. “Sanoop is a really stupid squid.”

“That’s not very nice,” Sukie told him. “And very judgemental.”

“It wasn’t me who said so. It was written in three foot high letters on the side of the White Cliffs of Dover in the year 3567. His own father wrote it - a very intelligent squid who was fed up of coping with his son’s mistakes. He’ll probably mess up on his first clue and be sitting here disconsolate when we all get back.”

“Maybe he’ll surprise everyone,” Vicki remarked. “And win the competition.”

“It would surprise his father,” Earl conceded.

It surprised Jimmy that sentient squid with Human features lived in the Solent in the thirty-sixth century. Earl was explaining about the Poonish migration and their settlement in suitable salt waters around the British Isles when Team Campbell-Gregory was called. Sukie went to collect the envelope.

“I remember your brothers competing a few years ago,” said Lord Arthur Sweetwell to her with a pleasant smile that revealed two gold teeth. “Good luck, my dear.”

“Thank you,” she answered and took her envelope, wondering if a curtsey was appropriate. She made do with a handshake and stood back as Team De-Lœngbærrow-Forrester was called. Vicki and Jimmy came up to Lord Sweetwell together. He shook both their hands and asked Vicki to say hello to her father for him. She promised to do so and stood back until everyone had received their envelopes.

As Lord Sweetwell retired back into the Staff Only broom cupboard the first train of the day rushed past, not stopping at this station. The competitors began to make their way to the ‘up’ escalator – all but Sanoop, who aimed for ‘down’ and got in the way of the first ordinary commuters coming to the platform. Vicki shook her head and hoped he would get his act together before the Quest was over.

“Well, here’s where we go our separate ways,” Earl said as they emerged from the station. His time car was parked in a side street opposite. Vicki’s TARDIS was on the traffic island next to the statue of Richard Cobden that still stood over four hundred years since his important role in late-nineteenth century politics.

“Good luck,” the two young men said to each other. The girls hugged, then Earl took Sukie’s hand as they crossed the road. Vicki and Jimmy did the same. When they reached the privacy of the TARDIS console room Vicki opened the envelope.

“Enjoy three courses on Sir Thomas Lipton,” the clue said.

“Three courses of what?” Jimmy asked. “Do we have to go back to school?”

“Sir Thomas Lipton….” Vicki was thoughtful. “There used to be a brand of tea called Liptons. Grandma Jackie sometimes buys it when she visits her own century. She says they don’t do tea bags in the twenty-third century like they used to.”

“Three courses of tea?” Jimmy pondered. “No, that doesn’t make sense.”

“This does, though.” Vicki had looked up Sir Thomas Lipton on the TARDIS databank. “We need to go to the East End in 1900 or so. I’ll set the course and you keep an eye on it while I go look for some things we’ll need there.”

“Bring a wooden brick from an old street,” Earl read.

“Wooden brick?” Sukie was perplexed. “Surely bricks are made of… well… brick.”

“Bricks can be made of anything as long as they’re evenly sized and fulfil the purpose of fitting together into a structure,” Earl told her. Sukie grimaced. She really didn’t like being taught such elementary things. It was bad enough at school. “But what does it mean by an old street? Aren’t they ALL old? Most of London was built in the seventeenth century. Even the twentieth and twentieth century redevelopments didn’t alter the layout of the streets all that much. As for the post-Invasion decades….”

“There is a place CALLED Old Street in the East End,” Sukie said, taking advantage of the fact that she was a local girl and Earl came down from Lancashire to be with her, but always feeling a little out of his comfort zone in London. The balance was restored as they each supplied a piece of information to the other.

“That gives us a location, then. We really don’t know WHEN we need to be there, though.”

“Let’s have a look and see if it gives us any ideas.”

The TARDIS arrived in the not too originally named ‘City Street’ in the autumn of 1900. It was a blustery day. Jimmy pulled the dark coat that Vicki had given him close around him. Underneath he was wearing a very poor, thin cotton shirt and a pair of trousers that were just about holding together. The shoes on his feet had holes in the worn down soles. The ensemble had been completed with a cloth cap, but he stuffed it into the coat pocket to avoid it being blown off in the wind. His naturally curly red hair was blowing across his face but there was nothing to be done except to get indoors very soon.

Vicki was dressed in a plain navy blue dress that went down to her ankles where button up shoes started. She had a woollen shawl around her shoulders and a bonnet on her head. All she needed was a basket of flowers or clothes pegs to be a late Victorian street seller.

And yet they were only clothes. Underneath she was still the daughter of an aristocrat. The way she held her head, the way she walked, was like a duchess. It worked in those fifteenth and sixteenth century houses they so often visited, wearing scarlet and gold, but not so much here in the East End trying to look like a commoner.

“This is where we’re going,” she said, stopping by a large building with a white and brick-red façade. It looked like a bank or a gentleman’s club, something exclusive that wouldn’t let people dressed like them in the front door. But curiously a steady stream of people in well-worn working clothes were heading through the doors.

Jimmy looked up. Above the main entrance in a strangely elaborate font it announced itself as ‘The Alexandra Trust Dining Rooms’.

“It’s a restaurant?” he queried. “For poor people?”

“Yes, that about sums it up,” Vicki answered him. “Come on.”

They went inside where the decoration was clean and functional. At a small desk a neatly dressed woman took money and gave out tickets. Vicki produced three small silver coins from a purse – three Victorian three-pence pieces, adding up to ninepence in the currency of the time. She received two tickets for the first floor dining room.

“Three courses for four and a half pence,” she explained as they mounted the stairs. “I’m treating you to the top of the menu. The two and a half pence dinner is on the next floor up and the half penny and penny meals are on the top floor.”

“The poorest climb the highest?” Jimmy noted.

“But the kitchens are on the top floor so they get served first.”

They came into the huge room where some fifty or sixty people were already seated at clean wooden tables and joined the queue at the serving hatch. They were given a bowl of steaming vegetable soup each with a hunk of bread and chose steak pudding and vegetables for their main course and a raisin pastry for their dessert. They sat at one of the long tables to eat with cheap but serviceable cutlery.

“This is good,” Jimmy admitted as he ate his soup. “There were plenty of times when my dad was too drunk to give me any tea I’d have been glad of this much food, let alone three courses. Is four and a half pence a lot in these days?”

“It would be a treat for working people, I think,” Vicki admitted. “The half penny meal is soup, pastry and a mug of tea or a bowl of porridge with bread and jam.”

Jimmy nodded. In a century when nobody was supposed to go hungry that half pence meal would have looked like a banquet to him. He understood fully how important a cheap meal must have been to people in this age when poverty was taken for granted.

“Sir Thomas Lipton made his money with the tea,” Vicki explained. “But wanted to give something back. So he opened this place providing hot food for the poor of London. The idea was that this didn’t look or feel like charity. The meal was paid for. It was just far cheaper than a profit-making café or restaurant.”

“There must be people in this time who couldn’t even raise the half pence, though,” Jimmy commented.

“Yes, there must be,” Vicki agreed. “But Victorians, even the generous ones like Sir Thomas, generally believed that poor people had to help themselves. They provided this food for those who made the effort to earn their victuals. They had no time for those too lazy to work or who wasted their money in gin houses and gambling dens. I know that’s not quite fair. I’m sure there are people who do none of those things but still have no money for food. But that’s how it was.”

Jimmy nodded and appreciated his four pence-ha’penny luxury meal all the more.

“What does it have to do with the Quest, though,” he asked as he tucked into the steak pudding and boiled carrots.

“It’s this,” Vicki answered, showing him the ticket that had admitted them to the first floor dining room. In very small letters around the edge was the next clue.

“How does that work?” Jimmy asked. “Do ALL the tickets have the clue on or just the one you got, and if so, how did the woman at the door KNOW to give it to you?”

“I have no idea,” Vicki admitted. “If I didn’t know better I’d say it was magic. I think we just have to take these things for granted a bit and not question them.”

“I’m surprised your father put up with that,” Jimmy remarked. “He seems like somebody who would get to the bottom of mysterious things like that.”

“Ordinarily, yes,” Vicki agreed. “But I think he liked the Quest too much to worry about getting under it.” She pushed aside her main course plate and pulled the warm raisin pastry in front of her. “I wonder how Sukie and Earl are getting on?”

Sukie and Earl weren’t so very far away. Old Street was only around the corner from City Street. But they were, of course, in a different time. They stood on the pavement in their own era and looked at a section of carefully preserved wooden brick road. There was an interactive tourist information panel nearby which actually had a very shaky bit of black and white film showing a horse drawn hansom passing over the wooden bricks in the 1880s. The information panel explained that the bricks were quieter and safer than stone or traditional cobbles when horses hooves and steel rimmed wheels went over them, but the idea was never widely utilised.

They had been laid down tightly to leave no gaps, soaked in creosote to make them waterproof and prevent rotting. Four hundred years later they still looked quite good with a bit of care from the National Trust.

“I don’t think I’m going to try prising one of those up,” Earl admitted. “It’s almost certainly against the law as well as tricky.”

“I think it would be just as difficult back when they were made,” Sukie agreed. “How are we going to do this?”

Earl looked at the information panel again and then turned with a grim smile.

“I’ve got an idea. It’s a bit risky, but it’s worth a try.”

They returned to Earl’s time car, still in its default form as a twenty-first century Toyota Prius. He set a time co-ordinate and initialised the perception filter that would make it virtually invisible in the period they were aiming for.

They arrived in Old Street just after dawn on a crisp wintery morning. Sukie recognised the era at once. All of the shops and the living quarters above had their windows criss-crossed with tape and blackout curtains inside. This was the Second World War of the twentieth century.

A bomb had fallen somewhere close during the night. The smell of high explosives and burning hung in the air.

“Look,” Earl said. “The force of the explosion dislodged some of those wooden bricks. They’re just lying around, now.”

“Yes, I see that,” Sukie answered. “But….”

She watched as a man emerged from the side door of a draper’s shop and looked up and down the street before heading to the place where the bricks were loosened. He grabbed a handful of them and scurried back inside.

“Was he one of the Mornington Crescenters?”

“No, just a local taking advantage of the chance of free fuel,” Earl answered. “Creosote coated wood will warm his flat for a day or two.”

“Those bricks are antique,” Sukie protested. “He’s just going to burn them?”

But it was wartime. Everything was short. Who could worry about antique road materials when they were struggling to keep warm? It made sense. Besides, at least one section of it was left for posterity. They had seen it in their own time.

“No need for you to go out,” Earl told his girlfriend. He slipped out of the car and checked that nobody else was out and about before grabbing just one of the bricks and bringing it back. An ARP warden and a police constable both came around the corner a second after he was back inside the hidden car. He and Sukie watched as they examined the damaged road before moving on to more important matters.

“I wouldn’t have wanted to explain myself to them,” Earl admitted. “Mission accomplished, though.”

He examined the brick carefully, then examined it again in the blue light of a sonic screwdriver. Sukie breathed out in surprise as letters showed up on the underside of the brick. The same thing occurred to her as occurred to Jimmy about the dining room ticket and must have occurred to every competitor in every year of the Quest.

Just HOW did the clues get onto a randomly chosen object like a road brick?

She dismissed the question from her mind as Earl read out the next clue.

“Find St. Olav’s Longship.”

“Are we meant to go back to the Viking invasion of England?” Sukie asked. “Did the Vikings actually come to London, anyway? I thought they were mostly in the north.”

“All I remember about Vikings is a very dull lesson at primary school naming all the Lancashire towns ending in ‘ton’ or ‘ham’ which suggested Viking roots. There are ‘tons’ and ‘hams’ in London, too. Leyton, Peckham…. I’m not sure if they’re Viking settlements or not. But if we have to go and find them in the ninth or tenth century we’d better find some peasant clothes and try to look inconspicuous.”

“I still don’t see how we can bring a longboat. They’re huge. The entrance to the tube station isn’t anywhere NEAR that big.”

“Let’s find out who St. Olav is, first, and what he has to do with longboats and London.” Earl reached for his palm-held computer and tapped on the screen with the mini-stylus. Sukie leaned close to see what it had to say.

“Find Judge Jeffrey’s noose at Execution Dock,” Jimmy read on the ticket as they stepped into the TARDIS.

“I don’t like the sound of that,” Vicki replied. “Execution Dock is where they hung pirates and rebels. I don’t think I want to see that.”

“Who is Judge Jeffrey?” Jimmy asked. “Yes, I know, it was probably in our history lessons and I should have been paying attention, but… well… you know me. I never really saw the point… at least until I started going around with a girl who could actually GO to history when it was happening.”

“I’m not going to THAT history,” Vicki insisted. “I don’t want to see people being hanged, even if they are pirates or rebels or whatever.”

“You might not have to,” Jimmy told her as he looked up Execution Dock and the infamous hanging judge of the Monmouth Rebellion on the TARDIS database. “I’ve found something here. I think it’s what the clue might really mean, anyway. Take us to Wapping in the year 2012. That’s when this webpage is from.”

Vicki did as he said, landing the TARDIS on the gravel ‘beach’ of the River Thames beside a narrow stone stairway called ‘Wapping Old Stairs’.

“We’re about a half mile away from where I wanted us to go,” Jimmy confirmed, checking an interactive map provided by the TARDIS. “But we could walk off the dinner along the riverside.”

“I’m up for that,” Vicki confirmed. “As long as we’re not going to see any hangings.”

It was low tide. The green tinge to the lower part of the stairs and the wall indicated how high the water could be – far higher than the roof of the police box shape Vicki’s TARDIS was stuck in. But there was plenty of time before it would get that high. They walked along the grey-brown gravel ignoring the brackish smell of low water and damp wood, past the foundations of a tall building with the words ‘Oliver’s Wharf’ across the top - just the first of such old riverside warehouses, some converted into luxury apartments for city-living singles, others falling into dereliction. At one point they had to go under the pier of the modern River Police headquarters. Vicki didn’t like the damp, murky smell and the dim light very much, but Jimmy’s hand folded tightly around hers and she felt safe with him.

There was a slight curve in the riverbank as they reached the high wharf and floating dock at Wapping New Stairs. The ‘beach’ was narrow for a while and they both glanced at the high water mark nervously. It widened out again as they came around the curve, though, and the gravel gave way to a slightly dirty sand that was much more pleasant to walk on. They sat on a low wall near Wapping Pier, a stop on the passenger ferry route along the Thames and Jimmy surprised Vicki by pointing out that they were actually sitting on top of the Brunel Thames Tunnel.

“During the Dominator invasion, some of us kids hid in the Underground. They didn’t seem to know about them. We slept in the trains that had just stopped wherever they were when the power went out, or on the platforms. We came up at night and got food from the abandoned shops, then hid down there in the daytime. I spent most of the time down there in the old Brunel tunnel. I never really saw what it was like up here in daytime. It’s a bit strange being here now, remembering….”

“You must have been scared,” Vicki said to him.

“I’d been scared most of my life,” Jimmy admitted. “The Dominators were no worse than my dad as far as I felt. I just hid from them the way I used to hide from him when he was drunk.”

Vicki tightened her hold on his hand as he had done when she was nervous under the police pier.

“All that’s over now,” she assured him. “We’re all going to be fine.”

He shifted his other hand until his arm was around her waist, and she turned her head until he could kiss her. Far below them trains were travelling under the Thames. The width of the wharf buildings away there was traffic on Wapping High Road. In front of them one ferry went upstream and another passed it going downstream. Where they sat, though, they were in a small world of their own that nobody could reach into.

“We’d better get on before the tide DOES come in,” Jimmy reminded her after a while. He slipped off the wall and reached to lift her down before they walked on again.

“St Olav was a Norwegian saint,” Sukie explained as they walked in the former docklands area of East London, only about a half mile and five years away from where Vicki and Jimmy were. They had left the Blitz and come to the early twenty-first century because it was a relatively benign era to explore the area. “He was a king of Norway, and supposedly brought Christianity to the country, which is why he was canonised. He’s also the patron saint of Norway. But none of that is really important. It’s because Norwegian ships used to come into the Docks around here, and the sailors established their own church – St. Olav’s.”

They stopped in front of a clean, neat building of red brick and white stone with a bronze spire on top of its squat tower. A Norwegian flag flying from a pole and a sign on the gate that read ‘Sjømannskirken – The Norwegian Church in London’ made its function and origin perfectly clear.

“What about the longship then?” Earl asked.

“Up there.” Sukie pointed to the spire where a weathervane in the shape of a Viking Longship, symbol of Scandinavian sea travel through the ages, was fixed.

“Right.” Earl breathed through his teeth thoughtfully. “You realise there is no way we can get that without committing an act of vandalism and theft, as well as desecration of consecrated ground.”

“Yes,” Sukie admitted. “I know none of those things are good, but granddad says all the things that are taken get put back almost straight away. No permanent harm is done.”

“There’s also the question of how to get up there.” Earl stood back and looked carefully. There WAS a small parapet all around the base of the spire. There was probably some sort of access from within the church. He COULD get up there.

“No,” he decided. “No, I can’t do it. I won’t. Not like that. It’s just not right. We have to think of something else.”

“Let’s go inside and look around,” Sukie suggested. “Maybe we’ll get an idea from it.”

She didn’t really want Earl to steal the weathervane from the top of the church, either, but she couldn’t think of anything else just now.

The church was worth visiting even without an ulterior motive. Neither of them were especially religious, but the stained glass windows depicting Norwegian saints and martyrs were beautiful in the sunshine and the nave had a quiet serenity about it. They sat in one of the pews quietly for a while, just enjoying that peace.

“Can you imagine having a wedding ceremony in a lovely place like this,” Earl whispered. Sukie was surprised. She had been thinking the very same thing but she hadn’t expected it from Earl.

“I don’t think we could fit all of our family into this little place,” she answered. Earl laughed softly and they both thought briefly of the complicated affair getting married by the Gallifreyan tradition was going to be.

“We don’t have to think about that for a few years, yet,” Earl reminded her. “Let’s think about this immediate problem a bit more.”

At the back of the church there was a small exhibition of photographs and memorabilia about the history of the church and the Norwegian community in London. There was a particularly interesting bit about the Second World War when the Norwegian government in exile and many resistance fighters working with the Allies came to services and used the Seaman’s mission attached to the church as a meeting place.

“Courage in the face of tyranny,” Sukie noted. “That’s something my family have always believed in. My father fought the Daleks just as these people fought the Nazis, and my brother, Davie, was the first to launch an attack on the Dominators.”

Earl had been born into a time of peace when nobody had to fight for their freedom, but he had been with Sukie and her family often enough to understand fully how they felt about such things.

“I’m going back into the church to light a candle,” Sukie told him. Earl stayed to look at the photographs. Before she returned, having paid her small tribute to freedom fighters of all times and places, he had found the clue he needed to complete their quest.

“The church was built in 1929,” he said. “Let’s go.”

“This is where we’re heading,” Jimmy said as they approached another set of stone steps. “Unless my map-reading is totally wrong these are the Pelican Steps – because the inn that once stood right here was called The Pelican. This is a later one called The Prospect of Whitby.”

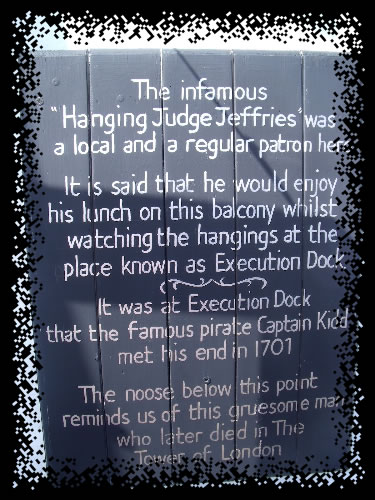

He turned from the steps through a side entrance into a cool, dimly-lit bar with a stone-flagged floor that was obviously much older than the rest of the building – a remnant of The Pelican. Jimmy looked around and then headed towards the outdoor balcony where the seats overlooked the river. A waiter followed them out and took an order for coffee before Jimmy drew Vicki’s attention to a plaque on the wall.

“The infamous ‘Hanging Judge Jeffries’ was a local and a regular patron here. It is said that he would enjoy his lunch on this balcony whilst watching the hangings at the place known as Execution Dock. – it was at Execution Dock that the famous pirate Captain Kidd met his end in 1701. The noose below this point reminds us of this gruesome man who later died in the Tower of London.”

“That’s a slightly confusing last paragraph,” Vicki pointed out. “It sounds as if it refers to Captain Kidd, not to Jeffreys. I’d have re-positioned the bit about Kidd after it to avoid ambiguity.”

“You’ve spent TOO much time in English class,” Jimmy replied. “Besides, this is what we came to see. Look over there.”

Vicki looked over the balcony parapet and there was a stout wooden structure there. The cross piece had a noose hanging from it.

“It’s not ACTUALLY one used to hang anyone,” Jimmy explained. “Just representing that time.”

“But it fulfils the quest.” Vicki nodded in understanding. “Yes, that’s better. But how are we going to get it?”

“I was thinking of your sonic screwdriver or something,” Jimmy added. “Let’s have coffee first, though. I enjoyed dinner, but I wish we’d had a drink instead of the pastry.”

The coffee was pleasant. They were alone on the balcony. It was still early in the opening hours and the few other patrons were inside. They could talk freely of things they couldn’t mention in front of other people.

“It felt good ordering the coffee,” Jimmy said. “Usually I don’t have enough money to do things like that. Is there ALWAYS cash in the TARDIS?”

“Yes,” Vicki answered. “The TARDIS can provide currency in any time zone or denomination. It comes, eventually from my bank account, the fund daddy set up for me so that I don’t get stuck without money on any planet where it is needed.”

“So really YOU paid for it, not me,” Jimmy noted.

“Does that really matter?” Vicki asked.

“It kind of does. When we were kids it didn’t matter so much. But now that we’re older… I mean, what happens when we get married?”

“We’ll have a joint account and what’s mine is yours and vice versa.”

“Yes… but… I don’t have anything. And even if I get into college and study engineering, like I want to do, it will be a long time before I can earn the sort of money you’re used to.”

“I’m not really used to a LOT of money,” Vicki reminded him. “I just know I don’t have to worry about where it comes from. But I don’t have lots of expensive clothes and jewels and stuff. I don’t really intend to have things like that. I don’t need them. I have a TARDIS and I can go anywhere in time and space and see wonders most people can’t imagine. That’s all the treasure I need. Besides, we live in the twenty-third century. Men don’t HAVE to be the ones who buy everything. We’re supposed to be equals.”

“I know. But we’re NOT equals that way and sometimes I wonder if it will be a problem.”

“Not if we don’t make it one.”

“Aren’t I supposed to give your father money to marry you?” Jimmy asked. “Isn’t that what they do in your culture? Earl was saying that he has a bank account set aside to make the bond of something or other for Sukie.”

“Bond of Intent,” Vicki said. “You can do that when I’m sixteen, and a Bond of Betrothal when I’m eighteen. “But the amount is dependent on how much you HAVE, like a percentage. So you don’t have to pay as much for me as Earl does for Sukie.”

“So you’re cheaper than Sukie?”

They both laughed at how that sounded. It was better than being offended about it.

“No, I cost just as much proportionally. But seriously, don’t worry about it. We’ll work it out when the time comes.”

That didn’t quite ease Jimmy’s mind about being a pauper who wanted to marry the daughter of a Lord, but there was nothing much he could do about it just now. He drank his coffee and looked at the noose, thinking about it carefully.

“I could jump from here and climb up that,” he said. “The noose is only looped over the crossbar. It would slip off easily.”

“Yes, but you’d be seen.”

“That’s where you come in. Can you do some kind of invisibility cloak or thing?”

“I can create a perception filter that would surround the gallows,” she suggested. “But it will be very difficult to maintain for long. You’ll have to be quick.”

Jimmy gave a wry smile.

“I’ve always been quick. Remember junior school when I always climbed the PE equipment faster than anyone else.”

“You used to push the smaller kids off,” Vicki remembered. “I’m glad you stopped being a bully when you got older.”

Communal living in a train tunnel almost certainly helped with his perspective of other people, she reflected. But it was probably better not to remind him of that again. She left her empty coffee cup and a tip for the waitress and went to the parapet. She carefully adjusted her sonic screwdriver so that it projected a perception wall around where Jimmy climbed up and swung himself onto the gallow post. He climbed as easily as he climbed the wall frame in PE class and shuffled along the cross piece. As he predicted, the loop was not tight and it could be slid off easily enough. He shoved it into his inside coat pocket and shuffled back until he reached the end of the crosspiece, then down the upright until he could reach the balcony again. He reached into his pocket and left a ten pound note under his coffee cup.

“A little compensation for loss of the noose,” he said. “Come on. Let’s beat it from here before they notice. We’ll walk up by the street route to the pub where we left the TARDIS and have another coffee there while we look up the next clue.”

Vicki agreed with that plan happily. She was the rich girl and it was her TARDIS that got them around, but she liked it when Jimmy had ideas of his own that she could go along with.

“I saw it in a picture,” Earl explained as they walked towards the building site where the new church was partially built. The tower was still to be finished, but the bronze spire had been delivered by the foundry that cast it in three large pieces. So had the weathervane. It was on a long piece of iron rod leaning against the wall of the incomplete tower.

“It’s not stealing, just borrowing,” Sukie said in justification as Earl climbed the fence and walked across the building site. He picked up the weather-vane and headed back with it. One of the builders challenged him and he spoke with a quiet, hypnotic manner, convincing the man that he was from the company that made the weather vane and he had to check it for cracks or imperfections before it was raised up above the church.

“That was a very good use of Power of Suggestion,” Sukie congratulated her boyfriend as they got into the disguised car and left 1929 very quickly. “I know it will be returned, anyway. It couldn’t be there in the future if it wasn’t. It would be a serious paradox, otherwise.”

“I’ll send them some money,” Earl decided. “The Wall Street Crash is about to have an impact on the whole world’s economy not long after the church is finished. There will be unemployed sailors in need of the Seamen’s Mission in the next few years. Something to help them out…. It would make me feel better for taking advantage of them.”

Sukie agreed. That made her feel better, too.

“Where next, I wonder?” she added. “There must be a clue on the longboat, somewhere.”

“I’m hungry. I hope the next spot has some good restaurants,” Earl answered. “If there are, then lunch is on me.”

To Be Continued....

|

|

|