Julia picked a fruit from the overhanging tree with its roots firmly buried

in the garden on the other side of the wall. They were a variety of plum

called greengage and they tasted very nice. There was a small bowl of

the stones. She looked at them and decided she had probably eaten enough

of them raw. She considered making a pie later. Or jam. Maybe both. She

had never made a pie for Chrístõ before. For that matter,

nobody had ever made a pie for him who wasn’t a servant whose job

it was to cook. It would be nice to do something like that.

Julia picked a fruit from the overhanging tree with its roots firmly buried

in the garden on the other side of the wall. They were a variety of plum

called greengage and they tasted very nice. There was a small bowl of

the stones. She looked at them and decided she had probably eaten enough

of them raw. She considered making a pie later. Or jam. Maybe both. She

had never made a pie for Chrístõ before. For that matter,

nobody had ever made a pie for him who wasn’t a servant whose job

it was to cook. It would be nice to do something like that.

For now she was content to sit there in the shade of the greengage tree and listen to the quiet sounds of a late afternoon in autumn in a small town in western France. There were children playing in a garden near by. Their game involved a little song chanted in unison. It sounded nice.

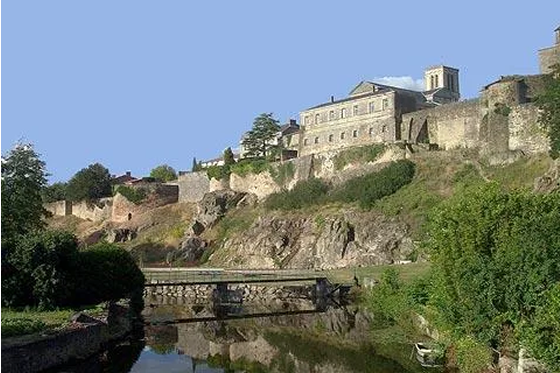

Nice seemed to be a good description of Parthenay Deux Severes generally. She had loved it from the first moment they arrived for a quiet week’s holiday away from Beta Delta. Chrístõ had brought them here in the early twenty-first century, a period he always felt comfortable with. And he had chosen late September when the sun was still warm by day and the evenings cool with spectacular sunsets to be seen from several very lovely places, including the citadel at the top of the town or from down by the river.

She looked around from her half-day dream as Chrístõ came into the garden with a fresh jug of iced lemonade. He sat and poured two glasses.

“What are you thinking about?” he asked.

“Pie-making,” she answered. “Greengage pie.”

“Aren’t you the girl who doesn’t eat puddings?” he teased.

“I was going to make it for YOU,” she responded. “But if you’re going to be silly, I won’t.”

“I would love you to make me a pie,” Chrístõ assured her. “But not tonight. There’s a special church service at Église Saint-Laurent. I thought we ought to go. It’s a thanksgiving service held every year on the anniversary of the day the Germans left the town at the end of World War II. Since we’re both supposed to be English it would be respectful even if...”

Chrístõ stopped mid-sentence. Julia knew what he was thinking. He came from a world that had been invaded by an enemy as bad as the Nazis who came to Parthenay more than sixty years ago. The idea of a service giving thanks for the end of the war appealed to him on a deeper level than the merely curious.

“It sounds like a good idea,” Julia told him.

“Afterwards we’ll eat at our favourite bistro in Rue Jean Jaurés. If the weather holds we might even sit outside under an umbrella.”

“Pie-making tomorrow, then,” Julia agreed. “Let me change into something suitable for the evening. It will be cooler when the sun goes down.”

He changed his shirt, from one black cotton one to another black cotton one under his leather jacket. Julia didn’t mind that he didn’t dress up. That was how she had known him from the first day she had met him. On Gallifrey and Adano-Ambrado he customarily wore robes – black for preference – but anywhere else he was comfortable in his leather jacket and black denim with a cotton shirt. And that was how she liked him.

They stepped out into the narrow, cobbled Rue Faubourg Saint Jacques where the shadows were already long and deep and Julia was glad of a warm cardigan over her dress. She held Chrístõ’s hand as they walked down to the castellated bridge over the river to the older part of the town where some of the houses dated back to the fifteenth century and were lovingly preserved and still lived in by modern families.

“I really do like it here,” Julia said. “I’m glad your father gave you the deeds to the house. Although I do wonder how he came to own half of a converted French coaching inn.”

“He bought the house as a place to bring my mother as a break from Gallifrey,” Chrístõ replied. “I think looking at a yellow sky got too much for her sometimes. And he found that little house for sale and bought it to please her. Now it’s mine... and yours. When we’re married and living on Gallifrey permanently, a place to get away to might be even more important than it is now.”

“Well, your father picked a wonderful place. It’s just right for us. All the neighbours think we’re on our honeymoon, you know.”

“I know,” Chrístõ noted. “I haven’t bothered correcting them. Have you?”

“No. It’s nice to pretend. Though, really... apart from I have my own bedroom, we’re living just like ordinary people do when they’re married. We buy food and keep the house tidy and do things together. I like it like that.”

“That’s what my mother must have liked,” Chrístõ said. “The chance to be Madam De Leon of Rue Faubourg Saint Jacques instead of Lady de Lœngbærrow of Gallifrey.”

He looked up at the spire of Église Saint-Laurent against a deep blue sky and thought about his mother and father standing in the same place, clutching hands lovingly. They had bought the house in the 1950s when there were less cars in the streets, no TV satellite dishes marred the look of the medieval weaver’s houses and neon lit signs on the shops were unimaginable, but their experience of Parthenay must have been much the same.

The church bells chimed as they made their way, along with many of the townspeople, into the eleventh century church. Julia put a lace veil over her head as she stepped inside and genuflected appropriately before the tabernacle. Chrístõ, who came from a race of people who were regarded as gods themselves, bowed his head respectfully before taking his place by her side. The religious devotions were not a part of his culture, but he believed in the reason they were gathered in this church on this evening and his thanksgiving for the end of the war in France was heartsfelt.

Near the end of the Mass, as he waited in his place while Julia went up to the altar for communion, he looked at the war memorial with French flags either side of it and thought about the war he himself had come through and the friends he remembered with melancholy.

Then he blinked and stared. He blinked again and wondered if he had been hallucinating. For a moment he thought he had seen a very different flag to the red white and blue tricolour of France.

He shook his head. Those were definitely tricolours. There was no mistake.

Julia returned to her place beside him. He drew a deep breath and got ready for the final part of the service. He told himself it was the dim light in that corner of the church and his imagination working overtime.

For that brief moment he was sure he saw Nazi swastika flags lining the wall!

When the service was over he walked out of the church with Julia at his side. It was starting to get dark, but the evening was calm and still. They chose to sit outside their favourite bistro in the Rue Jean Jaurés with the church bells marking the end of the Mass still pealing away. They chose from the menu and drank a non-alcoholic aperitif. The streets were busy with people enjoying the evening air. Music drifted from the pubs and bistros of the town centre, but none of it intrusive or annoying. It was a pleasant way to spend the evening and it took his mind off deeper thoughts that had pre-occupied him.

“You know, the priest said something in his sermon you ought to take notice of,” Julia told him when they were drinking coffee after their meal. “We shouldn’t forget the past. But we shouldn’t dwell upon it. I think that goes for a Time Lord who fought in the Mallus war as well as humans who fought Nazis.”

“Yes, it does,” he replied. “I quite agree. And I will try to remember it. There was something else I was thinking about. But... no, it really doesn’t matter. It was nothing. Take no notice of me. We’re on holiday. I’m not going to spoil it.”

He put everything else from his mind as he walked in the cool evening, under a velvet blanket of stars. The river Thouet was a dark ribbon through the earthly constellations of lights in house windows all over the town as they walked along its bank, delaying their return to the house in Rue Faubourg Saint Jacques a little longer. Not that returning to the house wouldn’t be a pleasant enough thing to do. They could make cocoa and sit in the kitchen by the solid fuel fire until they were tired and then go on to bed looking forward to another pleasant day in the morning, a day that included pie-making.

When they stepped up onto the Pont Saint-Jacques, though, something happened that soured the evening and worried Chrístõ very deeply.

“What’s that?” Julia asked suddenly. “That noise?”

“I don’t know,” Chrístõ answered. “It sounds like...”

Then he drew Julia close to him protectively. Both of them stared as a troop of marching soldiers literally appeared out of thin air on the far side of the bridge. They came towards them, boots sounding loudly on the stone bridge. When they reached the south side, passing under the Porte Saint Jacques, they vanished just as abruptly as they had appeared.

“Chrístõ!” Julia exclaimed. “They looked like German soldiers, from World War II. The kind that occupied this town.”

“Yes, I know,” he agreed. “But that isn’t possible. It must be...”

But there was no simple explanation. He knew in his hearts this wasn’t some kind of re-enactment group in costumes. The church service they had gone to earlier was proof enough that nobody in Parthenay was interested in re-enacting the occupation they had every cause to forget. And it wasn’t a film being made there, either.

For a few minutes, the German army had been on the bridge. Then the time anomaly snapped back into place and they vanished.

“Time anomaly?” Julia queried.

“What?”

“It’s what you just said. A ‘time anomaly’.”

“I don’t remember saying anything. But I was thinking those words. It can be the only explanation for what we just saw. I need to see if the TARDIS picked up any unusual readings.”

Julia sighed. She had hoped for no more this evening than a cosy time by the kitchen range. Now, something sinister had thrown it all into disarray.

The TARDIS was parked in the kitchen, disguised as a wooden door that went nowhere. Chrístõ left the door open as he worked. She could see him as she set to work herself at the cook-stove. When he emerged an hour later he was surprised to see two plates of caramelised greengage slices on crêpes with clotted cream.

“I’m still going to make a pie tomorrow,” she told him as he sat to eat. “Did you find anything out?”

“It was a very brief temporal rift, allowing an echo of the past to bleed through into our time,” he answered. “I didn’t know Parthenay was subject to them. Some places are. That’s where ghost stories come from. Haunted houses are usually on a temporal fault. Cardiff is on a massive one. That’s always been known. The Tower of London, any place you’ve heard of where people have sworn they saw something that shouldn’t have been there.”

“So it’s... normal... in a creepy kind of way. Natural...”

“Yes, and it’s nothing to really worry about. They looked frightening because of what they are... German soldiers in a place that they once invaded. But...”

“The swastika is only a symbol of evil because we associate it with them,” Julia said. “I read somewhere that it was originally a kind of early Christian cross that you see on old churches.”

“That’s right,” Chrístõ agreed. “So... let’s not let this spoil our holiday, or make us feel any less enchanted with this house. I’d still like to come back here again in the future, wouldn’t you?”

“Yes,” Julia agreed.

“And the crêpes are wonderful,” he added. Julia beamed happily at him. When they were married, there would be a full household of servants to cook for them, but she wanted him to know she was fully capable of fulfilling a wifely role, all the same.

The next morning, Julia baked pies and turned several pounds of greengages into jam which Chrístõ confirmed would come to absolutely no harm if it was transported in time and space back to the Beta Delta system before being eaten. After a lunch that he, himself made, proving he was capable of domestic duties, too, they walked down to the Parthenay citadel where there was an open air music concert going on. It was a pleasant way to spend the afternoon, with pavement cafés selling iced coffee when they were ready to sit down.

Then in an instant the happy mood was shattered. The music stopped as the modern square was filled with soldiers from more than sixty years ago who blocked the exits and forced the people at gunpoint to move into a small area of the square. There, they were roughly split into male and female groups. Julia screamed as she was separated from Chrístõ. She wasn’t the only one. Nobody understood why it was happening now, but they fully understood what was going on. During the Occupation it had been a common enough occurrence. If the local Resistance had been active the townspeople would be made to suffer for it. Men were taken from the crowd and shot randomly. Women would be taken and used in atrocious ways in order to complete the suppression of the local people.

Chrístõ knew that from the thoughts of some of the older people among the crowds, those who remembered it happening the first time. He reached out and held the arm of a white haired man who actually cried in fear and kept reciting the names of people who must have been killed long ago.

“Don’t be frightened, sir,” he told him. “This isn’t what it seems. It can’t be. They won’t... can’t... harm any of us.”

He wasn’t completely certain about that. These were not ghosts. They had fully corporeal form. He had felt that when Julia was pulled away and he was pushed back into the crowd of men. The temporal anomaly that had merely generated echoes last night, was now capable of pulling both times together in a terrifying way.

And it was going to end badly. The soldiers were pulling men out of the crowd, making them line up separately against the side of the town hall.

“No!” cried the old man. “No, not now. Please, not me. Anyone else but not me. Not again.”

“Leave him alone,” Chrístõ protested, putting his own body between the soldiers and the terrified old man. “He’s done you no harm. If you want to bully somebody, bully me.”

The soldiers looked at him for a long moment, then pulled him and the old man from the crowd. They thrust them both against the wall. Chrístõ tried to shield the old man, but it was all too obvious what was going to happen next. He tried to see Julia, but the women were being held back by a whole row of soldiers. He could hear their screams and sobs of terror, though.

He stared at a modern Citroen car parked illegally outside the town hall and sporting a ticket for it. It hardly seemed possible that he was about to be shot by a firing squad that belonged in the 1940s. He kept his eyes on the parking ticket fluttering in a slight breeze and wondered what his chances of survival were. If they missed his second heart, if he looked dead and they didn’t try to finish him off...

He heard the order to fire. He heard the volley. He thought he felt the air displaced by the bullets. But none of them touched him. He looked around. The soldiers were all gone. It was over.

Almost over. The old man he had tried to protect had collapsed. He made sure it was no more than a faint brought on by the shock. He did the same for several other people as the rest broke from the segregated groups and found each other again. They were all asking the same question. What just happened. Chrístõ wondered how they were going to explain what happened when the shock wore off and they realised that CCTV cameras around the square must have filmed it all.

“Chrístõ!” Julia wrapped her arms around him. He held her close for a long time, grateful for the chance to do so.

“Come on,” he said eventually. “I need my TARDIS. This isn’t just a harmless rift echo. Something is very wrong.”

Julia didn’t say anything at all. She clung to his hand as they hurried through the narrow streets of the old town and across the bridge where they had seen the first manifestation of the sinister temporal rift.

This time she didn’t bake while Chrístõ was busy in the TARDIS. She came into the console room and watched him working.

“I was wrong,” he admitted. “It isn’t a natural temporal anomaly. It’s man-made. Somebody in the area is trying to undo time. The signature is unmistakeable this time. The anomaly went on for so very long, and the TARDIS recorded it all.”

“But who would do that?” Julia asked. “Who would know HOW to do it? This is Earth in the twenty-first century, not Gallifrey.”

“The basic principles of temporal mechanics aren’t difficult. A particularly gifted Human physicist could figure it out. And if he kept plugging at it, he might be able to build a crude device. He’s got to be stopped before he draws the attention of the Time Lords.”

“He has. You’re interested.”

“I mean the not so nice ones. The ones who regard time as our exclusive domain. They’re not always kind to primitive people who try to get in on it. In our darker past we’ve destroyed races that got too close to our secret. As for this man... well, the CIA have agents out all over the galaxy ready to stamp on unauthorised time experiments.”

“Hext sends men out to hurt people who build time machines of their own?” Julia was appalled. “But he’s...”

“He’s a good friend to us both, yes. But he’s also the director of a ruthless organisation. And, yes, his agents do that sort of thing all the time. I can’t stop it. And... as a Time Lord, and as a de facto CIA man myself, it is my duty to deal with the Human who is playing such dangerous games here in Parthenay.”

“Not...” Julia’s face was pale and drawn. “You don’t mean... by assassinating him?”

“No,” Chrístõ replied. “Certainly not. But I’m not going to be kind. Look at the distress his experiments have caused. There were men and women among those crowds who thought they’d seen the last of Nazi’s with guns pointed at them. They were terrified. And if the rift had stayed open a few more seconds...”

“Oh, don’t remind me,” Julia groaned. “I really thought...”

“So did I. As it is, it’s lucky there weren’t fatal heart attacks. When I get hold of him, I’m...”

He swore in Low Gallifreyan. Julia blushed. She didn’t know what the word meant, but she could guess.

“He’s opened the time rift again!” Chrístõ exclaimed. “It’s stronger this time. But more localised. I think I can get a fix on the location of the device. Grab a handhold. We’re on our way.”

Julia just had time to grab hold of the console before the TARDIS dematerialised rapidly and shortly after dematerialised with a bump. A strange looking machine that seemed to be made of cannibalised home computers and a large, pulsating crystal at the centre materialised in the middle of the floor.

“Is that the machine causing the anomalies?” Julia asked as she watched her fiancé yank the crystal from the machine causing sparks and arcing electrical energy and then a descending whine as the machine lost its power.

“I’ll deal with that later,” he said looking at the viewscreen long enough to note that they were in the ruins of the medieval castle at the top of the fortified town of Parthenay before he opened the door and ran outside. Julia followed a little more slowly.

What she saw when she stepped out of the TARDIS was one elderly man in modern clothes and a German officer from the second world war in his black uniform. The officer was kneeling and the old man had a gun to his head.

“Stop!” Chrístõ called out to him. “Stop, now. You’re doing something so terrible you can’t even begin to know what the consequences would be.”

“The consequence will be the death of this... this...”

The man was speaking French. Julia heard his words translated to English, except for the adjective he used for the German officer. That was translated to Low Gallifreyan, so she only had the vaguest idea what it meant.

Chrístõ knew exactly what it meant. But since the subject was wearing the uniform of the Waffen-SS, the epithet was redundant.

“It doesn’t matter what he is,” Chrístõ insisted. “You can’t just kill him. Not now. Not like this. Who are you? What’s your name?”

“Yves Musson,” the elderly Frenchman replied. “From Avenue Wilson in the Faubourg Saint-Jacques.”

“And you?” Chrístõ asked the SS officer in a chilling tone.

“I am Commandant Hans Koehler. I am an SS officer and you will both be shot for this. I demand you release me at once.”

“Shut up,” Chrístõ replied, and to Julia’s surprise the officer did. He looked from him to Yves Musson, who kept the gun pointed at the officer’s head. He noted that it was a Luger, probably the officer’s own side arm. “You brought him through time from the 1940s to kill him here, now? Why? The war was over in 1945. The likes of him got what was coming to them. Why do this?”

“For what he did to my mother,” Musson replied.

“Why?” Julia asked. “What did he do to her?”

“Mademoiselle, I could not say in your presence. It is not...”

The expression on Julia’s face made it clear she was working it out for herself.

“She never even told my father. She kept the pain and the humiliation to herself. But she wrote it down in a diary. I found it when she died, forty years afterwards. And I vowed I would make him pay. Except he was already dead by then. So I used my scientific knowledge... I was a physics research professor at University of Poitiers. I set my mind to finding ways of bending time. It took me all my working life and five years of retirement, but I found a way... not for me to go back in time, alas. I could not spare her his ravishment. But I could bring him to me and make him pay. The first time, the signal was too weak. Then it was too broad. It pulled dozens of those fiends out of history. But finally I calibrated it. And now he’s mine... I intend to kill him. But not before he suffers the worst tortures a man can stomach...”

“No,” Chrístõ insisted. “I understand your reasons, but I can’t let you do that.”

“Why not?” Julia asked. “It sounds as if he deserves it.”

“No. Because... the time rift is still open. I can feel it. And I can see the consequences. If Koehler is killed out of his time, before his time, then terrible things will happen. When he is found missing, his second in command will take terrible revenge on the local people. Suspected Resistance houses will be raided and people will be killed whether they are found to be Resistance or not. When that fails, the local people will be rounded up in the square and separated into groups. They will be shot systematically for not telling the truth about where the missing SS man is. And most catastrophic of all...” Chrístõ looked at Yves Musson. He was already very close to breaking. He didn’t need the other consequence. Those he had already outlined were enough.

“He’s my prisoner,” Musson insisted. “I’m going to kill him. And then...”

“You are a filthy French peasant, not fit to lick my boots clean,” Koehler growled.

“I told you to shut up,” Chrístõ snapped. But then Koehler moved faster than he expected. In an eyeblink he was no longer a kneeling prisoner. He was on his feet, throwing Musson to the ground and taking Julia as a shield. The blade of a knife glinted in the decorative uplighting that made the ruins stand out against the night sky. He was holding it against her throat.

Chrístõ adjusted a setting on his sonic screwdriver and held it up. The powerful magnet yanked the dagger from the SS man’s grasp. Chrístõ caught it in his own hand, but Koehler tightened his hold around Julia. He didn’t need a knife to break her neck.

“Let her go or you’ll be sorry!” Chrístõ told him. And very quickly his promise was kept, though not quite how he intended it. Julia’s elbow swung back into his solar plexus while her heel jammed into his instep. The pain from both injuries was enough to make him relax his grip and she finished him off with an upwards arm movement that bloodied his nose and a final raised knee that jammed into his groin.

“I’m impressed,” Chrístõ said as Koehler crumpled to his knees in pain and Julia stepped away from him.

“They do self-defence classes in the gym after tea on Wednesdays at my college,” she replied. She reached to pick up Yves Musson’s gun and passed it to Chrístõ. He made it safe while she helped the old man to stand. Chrístõ, meanwhile bent over the disarmed SS man, brandishing the knife close to his face.

“I see this isn’t just any knife. It’s an inscribed gift for a Hitler Youth who graduated to the SS. ‘Blut und ehre’ – blood and honour. You have no idea about either. If my girlfriend wasn’t watching I’d be glad to educate you. As it is, we’ve got more important things to do right now. Julia, take Monsieur Musson inside. I’ll be right behind you with this piece of scum.”

Julia gently led the quietly sobbing Frenchman into the TARDIS. Chrístõ was far from gentle as he pushed his prisoner through the doors.

“The ache in the pit of your stomach is not just because of Julia’s self-defence,” he told Koehler. “It’s because you’re outside your proper time and the TARDIS knows it. I’m taking you back where you belong in a minute. But there’s something I need you to see, first. Julia, you know how to put us into temporary orbit?”

Julia did know. Chrístõ opened the doors again and brought the SS officer to the threshold. He held him firmly by the shoulder and made him look at the glowing orb of planet Earth slowly revolving on its axis.

“That’s the world your insane leader thinks he can rule. Look at it. Then look at the universe beyond your solar system. Your Fuehrer is an amateur compared to some of the evil things out there. The mindless cruelties your sort have committed against your fellow Human beings are insignificant in the grand scale of things. But that does not excuse you. It does not make you any less sickening. It just makes it so utterly, utterly pointless.”

Koehler stared at the Earth and its moon set against an infinite starfield. He said nothing. Chrístõ pulled him back and pushed him down to his knees. He pressed his hand against his forehead and concentrated hard. Koehler groaned with agonies transmitted straight into his brain without actually physically harming his body. He kept it up for twenty long minutes.

“Chrístõ!” Julia cried out at last. “Stop. Please. He’s...”

“I’m just showing him a fraction of the pain he has caused other people,” Chrístõ said. “It’s nothing like what he deserves. Shooting him in the head would have been too simple, Monsieur Musson. Even you have no idea of the depths of depravity he has reached. He deserves much more.”

“Maybe he does,” Julia said. “But I don’t want you to do it to him. You’re... not... You’re not Paracell Hext. You don’t do torture. You don’t... you’re kind, gentle...”

“I’m what I have to be,” Chrístõ replied. “Nothing would give me greater pleasure than handing this piece of filth over to Hext. He really would make him pay with every inch of his flesh. But I can’t do that. He has to go right back where he came from, otherwise too many innocent people would suffer.”

“You’re going to let him go?” Musson was horrified, now. “But he will probably do those things anyway... out of evil minded hatred.”

“No, he won’t,” Chrístõ replied. “Because I don’t need to touch his vile flesh to make him hurt like that. I can do it any time I want. I can invade his mind any time I choose and torture him to distraction. And I will. That is a promise. He will suffer, Monsieur Musson, for everything he has done. But he won’t hurt anyone else, ever again.”

Chrístõ left Koehler kneeling on the TARDIS floor whimpering in pain. He set the TARDIS to the time and space co-ordinates it had already extracted from the makeshift machine.

“Interesting,” Chrístõ said as he noted the date on the perpetual calendar on Koehler’s desk in the SS headquarters in Parthenay town hall.

“What is?” Julia asked. She watched him press Koehler down into his seat behind the desk where he seemed, in a dark, sinister way, to belong, surrounded by swastika flags and images of Hitler.

“The date. Very interesting.”

“It was the furthest back the machine would go,” Yves Musson explained. “I don’t know why. I tried. I wanted it to go further. I could have stopped him hurting my mother. But it wouldn’t...”

It was the day before the date they had commemorated in the church yesterday, Chrístõ noted. The day the Allies liberated Parthenay. That massacre he saw in the alternative reality that Yves Musson would have created would have happened on the very last day of the Nazi hold over those people.

As it was...

“You do know that the war is lost, don’t you?” Chrístõ said to Koehler. “Only a deluded fool would think otherwise. Your tyranny is over, anyway. But in case you have any last cruelties in mind...”

Koehler groaned as his mind was filled with imagined agonies again. While he was still incapacitated by it Chrístõ laid his gun and his knife on the table in front of him and turned away. Julia and Musson stepped into the TARDIS before him. He closed the door and it dematerialised, the displaced air disturbing the swastika flags and blowing over a pile of unread mail in the commandant’s in-tray.

“Now for you, Yves Musson,” Chrístõ said. He put the TARDIS in temporal orbit again and brought him to the threshold. “That’s your world down there. That’s France directly below. It’s a beautiful place even though it’s been through seven shades of hell too many times. So beautiful, my father, who comes from a planet so far away you can’t see it from here, bought a house there, in the Rue Faubourg Saint Jacques. He loves this planet and despairs of the terrible things that happen on it far too often. So do I.”

“You... are... not Human?” Musson asked.

“No, I’m not,” Chrístõ replied. “I’m a Lord of Time, Guardian of Causality, Protector of the Matrix. Among my many duties I prevent foolish amateurs from doing the sort of thing you were doing. I should punish you for so many infringements of the Laws of Time.”

“Laws of Time? I didn’t even know there were...”

“Of course, you didn’t. Nobody of your race in this time does. That’s why your experiments are so dangerous.”

“Chrístõ, you can’t punish him,” Julia said. “He was just angry and upset at the terrible things that man did.”

“Yes, I know. And that’s why I’m not going to punish him. But I am going to do something about that anger. Nobody should be in so much pain for so long.”

He reached and touched Yves Musson’s head the same way he had touched Hans Koehler. Yves flinched away at first, but it wasn’t pain that was being inflicted on him. Quite the reverse. Chrístõ reached into his mind, found the source of his pain and anger and soothed it gently. He didn’t take away the memories. Leaving gaps like that would only be distressing. He simply took away the anger and the guilt and the desire for revenge and left his mind calm and untroubled.

“That’s better,” he said. “Now, Yves Musson, go in peace and enjoy your retirement in this lovely French town that my mother and father adored even though neither were natives of it.” He nodded to Julia and she opened the door. It was dark of an autumn evening and they were in Avenue Wilson where Yves lived. The old man stepped out of the TARDIS and looked back just once as an unexpected wind whipped around him, then he went home.

“Could you really cause Hans Koehler pain without being near him?” Julia asked.

“Only if I wanted a migraine for a week afterwards,” Chrístõ replied. “That kind of thought projection is hard work. Usually I find the fear of what I could do is enough. But in his case it hardly matters.”

“Why? What will happen to him?”

“Not much,” Chrístõ replied. “When the Allies arrived a day later, he had shot himself in the head, at his desk, where we left him.”

Julia looked shocked. Chrístõ knew what she was thinking.

“I don’t know. The timeline was in flux. I don’t know if he would have done that anyway, before Musson dragged him out of his time. A lot of his sort did, when they knew they would be arrested and tried as war criminals. It might not have been anything to with me. Even if it was, I’m not going to lose any sleep over him. And nor should you.”

He locked off the TARDIS and put it into low power mode before he stepped out into the warm kitchen of the house he and Julia had spent such a pleasant time in. He went to the cupboard where one of the pies she had baked earlier was nicely cool. He went to the fridge and found clotted cream then put portions into two bowls.

“After all that, we’re just going to eat pie and cream?” Julia asked.

“Yes. This isn’t going to spoil our holiday. It isn’t going to spoil how we feel about this house, or this town. When we leave, we’re going to take only precious memories of what a lovely time we’ve had.”

“Can we really do that?”

“Yes, we can,” Chrístõ promised her. “And we will. This pie is delicious, by the way. None of the servants at home can do better.”

|

|

|