Marion sighed contentedly as she stood on the footbridge called Passerelle Léopold-Sédar-Senghor and looked out over the river Seinne at dusk on a warm summer evening. Kristoph had decided that they both needed a few days of pure, uncomplicated romance, and he had done so in a way that was only possible for a Time Lord with a TARDIS and a disregard for an obscure rule that forbad the use of time travel for trivial purposes.

The old, staid Time Lords who wrote that rule would probably think romance was trivial.

Kristoph pressed a small brass key into her hand. She flung it into the Seinne. It sank immediately, of course. She didn’t even really see where something so small had gone into the water. But that didn’t matter. She knew it was there, along with many more such keys.

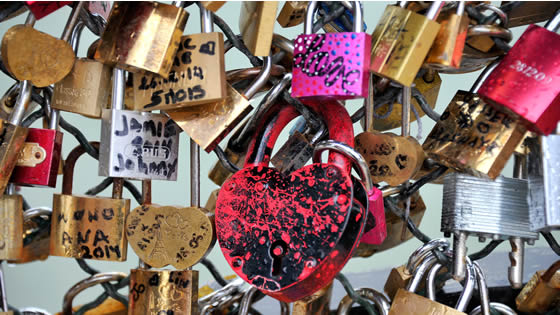

The lamps that lined the modern single span footbridge named after the first President of the former French colony of Senegal came on as she turned and looked along the length of it. The metal fence that protected promenaders and cyclists from falling into the river glittered in the warm yellow lamplight with hundreds of small objects fixed to it.

They were padlocks, ordinary padlocks sold in any hardware shop and ordinarily used for locking gates and sheds or bicycles. Instead of such mundane uses these had become lovelocks inscribed with the names or initials of sweethearts who fixed them to the bridge and then threw the keys into the water. It was a declaration of true love. Throwing away the key meant that the lock could never be unlocked and the love was sealed forever.

The one Kristoph had fixed to the bridge was unusual for two reasons. Firstly because the names had been carefully inscribed using a sonic screwdriver’s laser cutter set to the very finest point and secondly because the inscription was in Gallifreyan.

“All these people, so very much in love,” she said. “Or at least they were when they came here. Humans can be a little fickle, of course. It’s possible some of them fell out of love despite their lovelock.”

“You shouldn’t be so cynical, my dear,” Kristoph told her.

“I’m not,” she assured him. “Just realistic. It is a lovely idea, though. I had never heard of it before.”

“The tradition seems to have started in the early twenty-first century of your planet,” Kristoph explained. “After I took you away from Earth. There was something of a flurry of bridge building around the millennium and the lovelocks followed on from that.”

“That’s a strange idea to get my head around. A tradition STARTED in the few years after I left Earth. I always thought of that word meaning something that has been happening for many years before.”

Kristoph looked at her anxiously for a moment. Did that idea frighten her? Did she feel the many complications of being taken out of her proper time and place too keenly?

“It’s a nice tradition,” Marion said. “I hope it continues for hundreds of years. Though I do wonder what will happen if it does. There must be a lot of keys on the river bed already and there will surely come a time when there is no room for another padlock to be fixed to this railing. What will lovers in fifty or a hundred years think of the locks left by generations that are dead and gone?”

“They will think that love really is eternal,” Kristoph answered her. He reached out his hand to her and she took it readily. They walked back across the bridge towards the Rive Gauche where the TARDIS was disguised as a closed newspaper vendor.

Because delightful as Paris was on a summer evening was they had more to do. As the TARDIS slid easily through time and space Marion watched Kristoph inscribe another padlock with their names. Passerelle Léopold-Sédar-Senghor wasn’t the only place where love locks could be left.

After a summer evening in Paris, they stepped out into a cool spring morning in Copenhagen and walked across the still peaceful Bryggebroen – the Quay Bridge. This was not quite such a romantic spot as the river Seinne, perhaps. The footbridge linked two sides of an industrial harbour which was functional rather than aesthetic in its architecture. But a crisp blue sky was reflected in the quiet waters and Marion enjoyed choosing a spot along the length of the bridge where they could lock their love. When it was done, she threw the key in a long, curving arc that caught the morning sun and made it look like a small silver fish diving into the depths of the water.

Their next destination was the Brooklyn Bridge in New York. Here it was a little more difficult to drop the key into the Hudson. The pedestrian walkway was in the middle of the bridge with the lanes for motor traffic on a level below either side. Marion watched as Kristoph swung his arm strongly and let go of the key. It soared above the traffic and fell clear of the bridge to land in the river far below.

The Ponte Milvio in the northern suburbs of Rome was not a modern bridge built in the twenty-first century. It was actually one of the oldest bridges of all, completed in 115 BC. It had, of course, seen some renovations over the centuries, and the addition of street lamps to light it at night as well as posts at intervals along the ancient walls to which long chains were hung for no other purpose than to accommodate the love padlocks that could no longer be fitted to the lamps for fear of them collapsing.

Kristoph locked their lovelock in place and gave the key to Marion. She threw it into the Tiber and again sealed their love for each other.

“Most of these are young people,” Kristoph noted as he looked at some of the locks that had been placed there before them. “Young and hopeful, with their lives before them.”

“How do you know?” Marion asked.

“I can feel it when I touch the locks. These are emotional moments, and something of the excitement is left behind in the metal. I can sense it. “Carlo and Alessia. They are barely seventeen, full of the joy of first love, full sure that their feelings will survive school and college and looking for jobs, setting up a home together… children….”

“Will it?” Marion asked.

“That I can’t tell from such an echo of a moment as this,” he admitted. “Let’s be optimistic and think that they will. It seems a very long time since I was that young and certain about my future. Well, not THAT young, of course. Love doesn’t really enter a young Time Lord’s imagination until he is approaching a hundred and eighty.”

“And it was Lily who captured your hearts, of course.”

“If we had such a tradition as this on Gallifrey, I would certainly have inscribed a padlock with our names,” Kristoph admitted. “And I don’t think I would have been wrong to do so. We were in love. Fate intervened. She had every reason to think I was dead, and Jules offered her a quieter love, but one that was just as securely locked as any of these. And I… found my true love in the end. I wasn’t a youth by the time I came to that railway station waiting room in Leeds. I had every reason to be disillusioned with romance. But my hearts overruled my head.”

“I am so glad they did,” Marion told him. “You were definitely my first love… my only love.”

Kristoph smiled and took her hand. They walked back across the bridge to the TARDIS.

Their next stop was a warm June afternoon in Germany. The bridge they walked across was a functional yet curiously beautiful one made of strong box girders in two graceful arches. It had to be strong because the Hohenzollernbrücke carried trains from one side of the Rhine to the other twenty-four hours a day, passenger trains and long freight trains such as the one that passed noisily when they were halfway across. Marion put her hands over her ears. Kristoph hardly seemed affected by the sound or the wave of displaced air that caught them as the containers and flat beds and coal trucks passed them by.

When it was gone, Kristoph took the padlock from his pocket and found a place among the hundreds already hanging on the fence that separated the walkway from the train lines. He gave the key to Marion to throw into the river Rhine far below. She watched but it was invisible to her eyes long before it hit the water and sank down to the silt-laden river bed.

They carried on walking across the bridge. Two more trains passed them before they reached the far side. They walked a little further to the grand, beautiful, and fully restored Cologne Cathedral whose two tall spires were such an obvious landmark to the Allied airmen who bombed the city during World War II. For that reason, much of Cologne had a distinctly nineteen-fifties look to its architecture, but the Cathedral still managed to retain its earlier grace. Inside it was cool and quiet in the way that churches should be. They walked around hand in hand admiring the architectural beauty before they went back out into the noisy industrial city and crossed the river by the walkway again to get back to the TARDIS.

“One more lock to close,” Kristoph said. “Then we will have a romantic dinner for two as a perfect way to end a day like this.”

“Wonderful,” Marion agreed. She wondered where they might take their last lock. There were very many more places in Europe, indeed, all over Earth, where the tradition had blossomed – Brussels, Prague, Ucluelet on Vancouver Island in Canada, Pécs in Hungary, a bridge over a lake in Riga, the capital of Latvia, Mount Huang in China where it was thought the practice actually began.

But Kristoph had a more familiar place to bring her. As soon as she stepped out of the TARDIS she was struck by just how familiar it was, even though she didn’t recognise some of the newer buildings that had sprung up since she left her home planet in the early 1990s.

“Southport,” she said. “It feels like it. It smells like Southport. It really does. I can’t describe it, but it feels like somewhere I have known for a long time. Except it never had this before.”

She looked up at the cables of the elegant suspension bridge that carried vehicles and pedestrians across the far end of the Marine Lakes and on to the sea road. That wasn’t there in her time. Nor was the big swimming and leisure centre that she could see on the far side of it.

“I think that must be where the old open air swimming pool was,” she said. “There was a paddling pool for children, too, and a boating lake. They’ve got rid of all of that and built a big indoor place.”

It was probably better. An indoor pool could be used all year round, not just on the few really warm days of an English summer. It would have much better changing facilities and it would all be much safer and cleaner. But she felt a little nostalgia for the paddling pool her grandparents had taken her to as a little girl, where she remembered wearing a little swimming costume with a frilled skirt attachment like a ballet tutu. She had bright red water wings even though it was only a few feet deep and she couldn’t drown, and she remembered days that were scorching hot, when she had come out of the water to have her skin cooled with a pink lotion that dried with a chalky texture on her skin. For a moment she felt as if she could smell the camomile as well as the smells of the sea and the lake. She could hear the laughter of children splashing in the pool over the sounds of traffic on the new bridge and the screech of a seagull overhead.

“Yes,” she said. “This is a good place to leave out last lovelock,” she said. She took it from Kristoph and looked at their names engraved so carefully then she fastened this one to the railings of the bridge. Kristoph threw the key into the lake below. They grasped each other’s hands firmly.

“Where did you plan to take me for that romantic meal?” she asked him.

“I was thinking of going back to Paris, where we started. Some of those barges along the Rive Gauche are actually very fine floating restaurants.”

“Sounds good to me. But let’s leave it for later. I’d like to stroll along Marine Parade with fish and chips in paper.”

“I am Lord High President of Gallifrey,” Kristoph pointed out. “I don’t eat fish and chips out of paper.”

But he didn’t mean that. He gladly walked with Marion among the holiday crowds of Southport with that ordinary food in his hands. They would have the sophisticated dinner on the Seinne later.

|

|

|