“Why is your dad… I mean Mr Chandra… so worried?” Sky asked Rani. They were sitting together on the back row of seats set out in the Central Hall of the National Gallery for a slide show and lecture about art. Mr Chandra was near the front, talking to the assistant curator and glancing around him in a distinctly nervous way.

“Because the last time he took a group of students from Park Vale to an art gallery the Mona Lisa escaped from her painting and ran amok.”

“Oh.”

To anyone else Rani’s statement might have seemed odd, but Sky was created as a weapon of the Metalkind and after instantly transforming from a baby to a twelve year old girl was adopted by Sarah-Jane Smith. After that start in life as a human being nothing was odd to her.

“Mind you, that wasn’t at the National Gallery,” Rani added. “We could perhaps expect better behaviour from the paintings in here.”

Sky laughed along with her then turned to read the brochure she had been handed as they came into the Gallery. Rani looked around at the beautifully appointed hall that was, unsurprisingly given its name, the centre of the building designed at that time in the mid-nineteenth century when no expense was spared in public building projects.

She looked up past the richly gilded ceiling mouldings to the huge rectangular lantern window that let in natural light during the day.

It was evening. The sky above the gallery was a bluish-yellow-orange thanks to the light pollution of the city around it with just a hint of stars trying to be seen.

It was a magnificent room in a magnificent building. Almost too magnificent, perhaps, to play host to thirty fifth and sixth formers. Not for the first time, Rani couldn’t help wondering why, when the National Gallery decided to do special evening sessions for school groups, they hadn’t picked some expensive private school of the sort government ministers sent their children to instead of an ordinary comprehensive school.

Maybe because the children in those private schools saw art and culture all the time. It was the ones from the comprehensive school that needed the opportunity to visit the Gallery for a special after hours tour.

Why was that, she wondered. After all it was only a few pounds to travel from Ealing to the city centre by tube. The gallery with its thousands of valuable paintings was free. Why didn’t the kids of Park Vale ever come here?

Perhaps because it was just a LITTLE bit boring, she told herself. She looked around at the paintings hanging on the walls around them - a representative sample from the various collections in the sixty-three other rooms. She looked at the brochure in her hand and read some of the titles. Did even the private school students care about ‘Dido receiving Aeneas and Cupid disguised as Ascanius’ by Francesco Solimena. Did the private school students know who Francesco Solimena was without looking him up on Wikipedia? Did they know who Dido, Aeneas or Ascanius were? Was ANY sixteen to eighteen year old meant to know these things?

The Toilet of Venus DID interest some of the sixteen to eighteen year old boys, but only because Venus was a life size nude and one of the little naked child figures called putto was doing something rather strange with a feather. Some of the boys were still giggling about that one, much to her father’s embarrassment and chagrin.

She was pretty sure private school boys would giggle about that painting, too, but perhaps a little more discreetly.

One of Park Vale’s sixth formers was not giggling about a painting that didn’t actually include a toilet no matter how hard anyone looked. Instead, the boy, who Rani thought might be called Vince Noonan, was trying to talk to Sky about art.

“My favourite painting in the National Gallery is Turner’s Fighting Temeraire,” he was saying. Rani rolled her eyes. Turner’s painting was one of the highlights of the collection or British paintings, regularly voted as the nation’s favourite. But that was because it was one of the few paintings most people could name when put on the spot by a survey to find the Nation’s Favourite Painting.

“I prefer the early Dutch School,” Sky answered. “It’s hard to choose, but I think my absolute favourite is The Arnolfini Wedding by Jan Van Eyck. I like the way he paints the reflections in glass.”

Vince looked at her blankly, and Rani allowed herself a moment of smugness. The boy HAD mentioned the only painting in the building he had heard of. He couldn’t actually hold down a conversation about art for very long. Not with a girl who had most of human culture pre-programmed into her mind.

She looked again and wondered if Vince was using art as a way into a more conventional boy-girl conversation with Sky. That was an interesting idea. Sky hadn’t really had any regular kind or boyfriend in the usual sense during her time at Park Vale. She had met groups or friends at weekends to do normal things like shopping or ten pin bowling, and there were boys involved in the latter activity at least, but she hadn’t really been on a ‘date’. A certain shyness, perhaps, and a studiousness that would put off the sort of boys that giggle at the Toilet of Venus, had held her back a little.

Perhaps the time had come. Rani smiled and felt strangely old as she remembered when she and Clyde were told off by the deputy head for holding hands while wearing school uniform. It really did feel a long time ago. Now Sky was doing her A’Levels and attracting the interest of boys.

Vince was trying music as a subject when the main lights went down and the big screen for the slide show lit up. A man who introduced himself as Professor Andrew Norton-Ford stepped up to begin his lecture.

It was interesting stuff in its way. He talked about how art was a subjective thing, and that no two people would agree on their favourite picture. Rani smiled and wondered why, in that case, anyone needed to do a survey to find the Nation’s Favourite and why so many people – in spite of the professor’s assertion – chose the same painting.

But on the whole she agreed with the idea of a personal favourite. She wondered what her own answer to the question would be. She actually DID like the Fighting Temeraire, though she never would admit it. She liked Sky’s choice for much the same reasons as she had given. She liked Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus, though she wasn’t going to say so in front of either of her parents or any sixth form schoolboy.

Actually, in truth, her favourite painting was probably one of those she saw a few years ago at the Museé d’Orsay in Paris. It was probably treason to think such a thought in the National Gallery, but the impressionists and post-impressionists seemed a lot more fun than all the Renaissance artists with their obscure classical subjects that Professor Norton-Ford was showing on his screen.

She really was starting to get bored.

She wasn’t the only one. There was a distinct sound of snoring from the student on her left, a girl with a long pony tail who Rani thought might be called Josie Mattheson. On Sky's other side Vince was slumped with his eyes closed.

She looked across the rows in front of her. They were all falling asleep.

In the front row, her father was falling asleep.

“Sky....” Rani whispered.

There was no reply.

Sky was asleep.

Everyone was asleep.

Even the double-barrelled professor whose name Rani was struggling to remember as a strange weariness started to overwhelm her was slowly sinking to the polished floor beside his digital projector.

“Rani, Sky, wake up!”

The urgent voice of Clyde Langer close by woke Rani from a stupor while Sarah-Jane shook Sky and then resorted to a setting of the slimline sonic screwdriver that had superseded the sonic lipstick in her handbag. Sky stirred and woke.

“Mum, why are you here?” Sky asked. She noticed the empty chair beside her. “Where’s Vince?”

“Where’s everyone?” Rani asked, noticing how empty the Central Hall was. “Where's my dad? “

“We don’t know,” Clyde answered. “I was waiting at the Piggott entrance to meet you two after the lecture when Sarah-Jane turned up in a tearing hurry.”

“I'm double-parked,” she said. “But Mr Smith reported a surge of baratronic energy centred on the National Gallery.”

“Sarah-Jane's sonic is good for breaking into buildings,” Clyde added.

“It had to be,” Sarah-Jane continued. “There was nobody to let us in. This whole building is empty except for the four of us.”

“Which is really weird because there was definitely a man on the desk when I got here,” Clyde said. “The miserable old git wouldn’t let me wait inside. Said I was a security risk. But he’s gone now, along with whatever staff they have in here at night.”

“Where are they all?” Rani didn’t care too much about security guards, but she was worried about her father.

Very worried.

“I don’t know,” Sarah-Jane admitted. “But I intend to find out. “Come on. Let’s start with that screen. It looks pretty strange to me.”

Rani looked at the big digital screen that the images of dull Old Masters had been projected onto from the Professor’s laptop. The presentation had ended ages ago and now there was just a very strange, swirling, cloud-like pattern on the screen.

Rani turned her face away from it. Everyone did. There was something uncomfortable about those patterns – something malevolent.

Sarah-Jane moved closer, keeping her face turned away but aiming the sonic at the middle of the screen. There was a high-pitched squeal and then the screen shut off.

The difference was palpable. It was like when a supposedly silent washing machine finished its cycle and you realised there had been a really annoying noise there all the time.

“But everyone is still missing,” Sky pointed out. “Where are they?”

“They are appreciating art,” said a hollow voice. “From the other side, as it were.”

“What?”

Everyone looked around at the tall, thin man who stepped from the doorway. As he came closer Rani gasped in surprise.

“You’re Mr Lawrence Argyll, the public relations curator,” she said. “You’re the one who met my dad and arranged for this special tour and presentation.”

“What do you mean about them all appreciating art?” Clyde demanded. “What have you done?”

“All day, every day, people come to art galleries and look at paintings without ever really seeing them. The silly boys making coarse jokes about ‘toilets’, common tools who think they know art because they recognise a Madonna and Child from some Christmas card they got one year – the morons who say the Haywain is their favourite twentieth century painting or some such idiocy.”

“Yeah, so,” Clyde challenged him. “What did you do? And… how?”

“Ohhhhh!” Sky had stepped away from the sinister Mr Argyl. She had glanced at one of the paintings on the wall of the Central Hall. It was one of two rather similar pictures of fully dressed women sitting at a desk with a book- the Cumaean Sybil with a Putto and the Samian Sybil with a Putto.

The Putto in the Samian Sybil picture had Vince Noonan’s face.

“WHAT did you do?” Clyde repeated in a rather more threatening tone. Lawrence Argyll took a step back away from him and glanced at Rani and Sarah-Jane as if hoping for some glimmer of understanding from them.

Unsurprisingly he got none.

‘That screen is loaded with baratronic energy,” Sarah-Jane explained. “Baratronic energy causes matter to be transformed – in this case….”

Sarah-Jane swallowed hard. It was almost too horrible to think about, let alone express.

“Vince Noonan has been transformed from a flesh and blood boy to a painted figure on canvas?” Rani managed to say. “They’ve ALL been transformed… all the students, the professor, my DAD.”

Clyde had been contemplating the idea of thumping Mr Argyll, but was resisting because he was trying to rise above his delinquent youth and solve problems without violence.

So he really didn’t expect the powerful right hook Rani delivered square into the curator’s face.

“If people don’t appreciate art, its because art is BORING,” she said. “But seeing as this is the fourth most visited gallery in Britain, quite a lot of people must like being bored. So get Vince and everyone else BACK.”

“I don’t know how,” he protested in slightly muted tones. Rani might have broken his nose.

“I’m afraid he probably doesn’t know how to get them back,” Sarah-Jane admitted. “This is hardly human technology. He must have found it somehow. Alien technology is forever turning up on Ebay. But….”

Sky yelled again. Everyone, Including Mr Argyll, turned to look at her and gaped in astonishment.

She must have put her hand up to touch the painting of the Sybil and Putto. But instead of encountering a hard, unyielding canvas, her hand had gone straight through….

Into the painting itself.

“Vince!” she cried out and grasped the Putto’s chubby, pale, baby hand. She pulled, and her own hand came back into the real world still grasping the hand. For a strange moment the Putto appeared to be reaching out of the painting, then Sky fell backwards and Vince Noonan tumbled after her. They landed in a heap on the floor.

“What happened?” Vince asked in a wobbly voice. “I feel funny.”

“Carbon monoxide gas,” Sarah-Jane answered. “You’ve all been affected. Sit there a minute. If you’ve got any chocolate in your pocket, eat it. Don’t throw the wrapper on the floor. Stay where you are until we come back.”

“Come back from where?” Vince asked, but nobody answered. Clyde grasped Mr Argyll by the arm and twisted it behind his back.

“We don’t need to bring him,” Sarah-Jane said. She adjusted the sonic and aimed it at Mr Argyll. A silvery blue aura enveloped him and he became very still. “Temporary stasis cell. Lasts about two hours. If we’re not done by then, we’ll have a bigger problem.”

“What sort of problem?” Rani asked, catching the distinctly worried tone in Sarah-Jane’s voice.

“The transformation isn’t permanent, yet,” she explained. “That’s why Sky was able to get Vince back. But eventually…. Like paint drying, a jelly setting…. Look, we haven’t much time. We have to find all the missing people in pictures somewhere in this building.”

“We were here two hours before the lecture wnd didn’t even see everything,” Rani pointed out. “We’ll never do it in time.”

“We’ve got to split up," Clyde said. “I'll take the Sainsbury Wing. Sarah-Jane, you take the red section of the main gallery, Rani, the orange. Sky, the green."

Sky wasn't sure she wanted to walk around the Gallery on her own, looking for her school friends trapped in paintings, but there was no other answer. She headed through the right side of the hall.

“Hey… wait…” she stopped and turned to see Vince Noonan running after her. He stopped a few feet away and blushed feverishly. “Look… I… I mean… I don’t know what’s going on. But I don’t think it has anything to do with carbon monoxide and I don’t see why I should be left behind eating chocolate. Whatever you’re doing, I’ll help you.”

“I’m looking for students of Park Vale school who are… trapped in paintings,” Sky answered.

Vince looked at her, then looked past her at a large painting on the wall behind her.

“You mean… like them.”

Sky turned and saw that he had been looking at a family portrait called The Graham Children by William Hogarth. She remembered reading when she had been in this gallery dedicated to works from Great Britain 1750-1850 before the lecture that the baby on the left of the composition had died before it was finished. She felt glad that only the two girls and the older boy now had the faces of Park Vale students.

“You grab Toby Shanklin. I’ll get Rosa and Marie Russell out of it,” Sky said, reaching out to the picture. Vince hesitated only a moment before copying her.

The three youngsters popped back through to the real world, their mid-eighteenth century clothing instantly turning back to Park Vale uniforms. There was a certain amount of confusion before Vince explained slightly inaccurately what was going on.

“Come on,” Sky said as the three newly rescued students scoffed at what they had been told. “We have to find the others. There isn’t time not to believe that something weird has happened.”

“Weird stuff is always happening to us at Park Vale,” Marie Russell admitted. “Remember the Valentine chocolates a few years ago.”

“Right, so let’s go,” Sky insisted.

Sarah-Jane walked carefully around the section of the gallery with a silky red wall covering providing a neutral background for the art. She looked at each painting carefully but found no sign of Park Vale students in any of them.

Then, in the furthest room from the Central Hall, just before the corridor to the Sainsbury Wing, she looked very closely at a larg canvas by an artist she had never heard of, despite a good sound education – Jacopo Bassano. He was a sixteenth century Venetian and all his work - at least those on display in the National Gallery, - had Biblical themes. This one, The Purification of the Temple, had a lot of figures in it, including money lenders, women of ill-repute, a very large cow in the forefront of the image….

As well as six National Gallery security guards, still wearing their ID tags on their biblical robes and a woman with a striped apron and a four litre plastic milk bottle in her hand.

Sarah-Jane reached in and took the woman by the hand, first, noticing the faint tingle of crossing from one dimension to another. She had not felt it since the last time she stepped into The Doctor’s TARDIS, but she recognised it all right.

She reached again for the guards, each one emerging startled and confused.

“How did I get here?” demanded one of them. “Is it a security breach? I was on the desk… there was a cheeky lad trying to get in. Was he….”

“I was meant to be keeping the café open for a school group who are here, late,” said the lady with the milk carton. “I was offered overtime pay to stay on.”

“There’s no security breach,” Sarah-Jane assured the guards. “Go on down to the café, all of you. Have some tea and biscuits. Everything is just fine.”

Sarah-Jane wondered where she learnt to speak convincingly to people who really ought to have been asking her who she was and why she was there. She suspected it had a lot to do with knowing The Doctor, who never answered either of those questions unless a weapon was actually pointed at him or her – and not always then.

Anyway, the still slightly confused guards followed the tea lady towards the stairs to the lower level where the café was situated. Sarah-Jane checked for any more adults trapped in biblical scenes.

Clyde had hurried past the Venetian biblical painters to get to the Sainsbury Wing, the late twentieth century addition to the gallery that had been controversial at the time its architectural plans were revealed, but which looked almost sedate compared to some of the ultra-modern buildings like the Gherkin and the Shard.

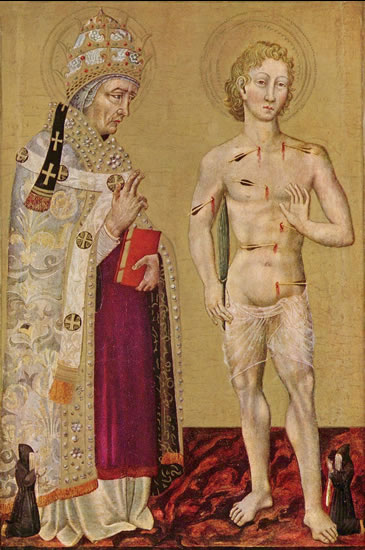

Clyde actually knew the National Gallery very well. As an art student he had visited more often than any of the former Park Vale students he was still friends with in adulthood. He knew that most of the paintings in the Sainsbury Wing would be uninspiring to most people. Nearly all of them were Medieval religious subjects, heavy on gilding, a lot of them portraying saints being killed in unusual ways. There were at least three Saint Sebastians pierced all over his naked body with arrows. Not having paid very much attention to RE classes, Clyde had no idea why Sebastian was killed in such an extreme way, but if the question ever came up in a pub quiz he would definitely know it.

One of the Sebastians caught his eye. The unlucky Saint was pictured in Giovanni di Paolo’s version with Saint Fabian who was looking much healthier in a bishop’s clothing.

But Sebastian’s face looked wrong for an early Christian martyr. For one thing he was wearing spectacles….

Clyde noticed the tingle, too, but having only been in the TARDIS a couple of times he didn’t recognise it the way Sarah-Jane did. All he knew was a hand grasping his and a cry of ‘oof’ as a man in tweeds fell forwards out of the picture. As Clyde helped him to stand upright something metallic fell onto the floor.

It was an arrow.

“Who are you, then?” Clyde asked.

“Professor Andrew Norton-Wood,” the man answered. “I was giving a lecture about art appreciation. There was something funny about the screen… I kept weeing shapes behind my slides…. Then… I don’t know…. It was like a dream. I could see the gallery, but I couldn’t reach it.”

“Did Mr Argyll provide the screen, by any chance?” Clyde asked.

“Yes, he did,” the Professor answered. “He said I just had to bring my laptop. It even connected remotely by the gallery’s WiFi.”

“Well, that explains that,” Clyde said, though obviously it explained nothing to Professor Norton.

Rani hadn’t found anything much in the first three rooms except some Dutch landscapes that she would have liked to have admired quietly and unhurriedly without a crisis to deal with. She was very worried about her father not only because she had to find him and get him out of a painting, somewhere, but also the aftermath of his rescue. She really didn’t want to be the one to explain to him what had happened to everyone, and she wasn’t sure which would be worse… him believing the incredible truth and never organising another school trip again, or him not believing a word of it and being angry with everyone.

In room Twenty-Seven, dedicated to the art of the newly independent Netherlands of the seventeenth century, her eye was drawn to a portrait by a man called Frans van Mieris the Elder. It was a rather nice picture with a title that explained everything – A Woman in a Red Jacket Feeding a Parrot.

Except the woman had the face of Josie Mattheson, the sixth former who had been sitting next to her at the lecture.

She hesitated for a moment, wondering what it would feel like to put her arm into a painting, then she plunged in, grasping the woman’s hand.

Josie Mattheson fell out of the painting, followed by a parrot that flew up to the ceiling and then came back down to her shoulder. She looked at it and gave it the rest of the biscuit she was holding for no obvious reason.

“Are you all right?” Rani asked her.

“I think so,” she answered. “I feel… odd… but OK.”

“We’d better….” Rani began. Then she heard a voice calling to her. It was Clyde and he sounded urgent.

“Go back to the Central Hall,” she said to Josie. “You’ll be OK there.”

Then she ran.

She reached room Sixty-Three in the Sainsbury Wing a little out of breath. It was quite a run through interconnecting rooms.

Clyde was there. So was the Professor and Sarah-Jane, who had obviously heard the call.

“It’s your dad,” Clyde told her. “We found him. But…."

She turned to the painting he was pointing to. It was Van Eyck's Arnolfino Wedding. She stared at the round mirror in the background between the two figures. It was widely regarded as a mark of Van Eyck's genius in creating the effect of reflecting glass with strokes of a paintbrush.

There was even a theory that he painted himself in the reflection.

But now, Haresh Chandra was reflected in the mirror, his mouth open in astonishment.

Rani tried to reach into him, but she just touched the hard, cold, mirror glass. She pulled her arm back and looked around at Clyde, Sarah-Jane, even the Professor for ideas.

"The thing is," Clyde explained. "Your dad is reflected in the mirror. That means he's standing in front of the Arnolfinis, looking at them… from our point of view."

Rani thought of all that. The answer was frightening, but obvious.

"I've got to go in all the way and get him," she said. "Then you can pull us both out."

"It's too dangerous," Clyde protested, "I'll go."

"It's dangerous for you, too," Rani pointed out. "But he's MY dad. I'll do it."

That was the only argument to be made. She took a deep breath, then two steps back, then ran at the painting.

She experienced the crossing of dimensions as a sharp tug in her stomach, and a brief sense of disorientation. Then she stood looking at two familiar people wearing rich Flemish wool garments who looked at her in some surprise.

"Excuse me, just passing through," she said, then turned around. "Dad… come on."

She grasped his hand and urged him forward, then reached out to the disembodied hand that appeared in front of her. She felt again the tug in her stomach and hoped she would never feel anything like that again.

She slipped out into the National Gallery and her father fell out after her. He blinked several times and stared around him.

"Rani, what is going on?" he asked. "Clyde… Miss Smith… why are you here?"

"I'll explain it over a cup of tea," Sarah-Jane told him. "I know for a fact that the café is open."

As they headed that way they met Sky with a large crowd of students. Mr Chandra did a quick headcount and declared that everyone was there except Josie Matheson. They went, en masse, to the Central Hall where Rani had sent her.

"We have a problem," Sarah-Jane said, looking around the Hall. "Mr Argyll is missing. The stasis cell mustn't have lasted as long as I hoped.

"He isn't a problem," Sky contradicted. "At least, I don’t think so. You know the painting called the Rokeby Venus.. by… I forget… A Spanish painter… Anyway… you know how it’s a nude woman with her back to us and her face in a mirror held up by Puttos…."

Everyone was visualising the very famous painting as she described it. Sone of the boys within hearing giggled as they remembered the lady's bottom featuring so prominently in the composition."

"Well…." Sky continued. "The face in the mirror looks like Mr Argyll, now. I think… anyone who isn't expecting it will still see the girl… but after the night we've all had, I think we'll know its him. And…."

Sarah-Jane looked at her watch. It was more than two hours since the crisis had begun. She looked at the readout on her sonic device to confirm. Only a very tiny, fast dwindling remnant of baratronic energy remained, possibly where the Rokeby Venus was displayed.

"Even if we run it'll be too late," she said. "I'm afraid he will have to stay here with his art. Come on. I think we all deserve a cuppa."

|

|

|