Jean dialled a familiar number on her mobile phone. The universal roaming card that The Doctor had inserted into it meant that she could call home from any place and any time and it wouldn’t cost her anything.

Or so he said.

If he got it wrong she was going to have a huge bill when she got back to Earth.

“Uncle Iain!” she exclaimed joyfully when the call connected. She heard his voice as clearly as if she was calling the Isle of Bute from Inverness. “Is Aunt Sheelagh there? Oh, I’m sorry I missed her. No, nothing’s wrong. I just wanted to let you all know I’m fine…. I’m on a planet called Ocean Blue – that’s the name of it, and the reason is that it is entirely covered with the bluest ocean you could imagine. It’s the colour of sapphires. And there’s a moon… well, it’s a planet, really – a twin planet. That looks blue, too. It’s setting in the sky, there’s only half of it to be seen now and the reflection of the planet in the water stretches for miles and miles so that it looks as if the blue is being poured out from the planet to the water. It’s unbelievably beautiful. We’re sitting on a raft. The Doctor landed the TARDIS on an old raft that was just drifting and we’ve been travelling with this whole group of people who live on rafts for a week now. It’s like a gypsy camp on water. They have houses on the rafts made of dried reeds and they just let themselves move on the current, not caring which direction they go. Yes, I’m having a terrific time. I REALLY wish you could see it. Working for U.N.I.T. you only see the worst of extra-terrestrial life, the ones trying to invade Earth. But this is something else.”

The Doctor smiled as he listened to Jean’s conversation with her uncle. Her description of planet-set on Ocean Blue was spot on. It really was one of the wonders of the twelve galaxies. He never tired of seeing it. He had visited this planet many times. It was a good place to relax a little and enjoy congenial company.

Well, as long as he didn’t tire of seafood suppers, anyway. A cheerful call came from the raft nearest to the one the TARDIS was parked upon. The brazier glowed and the supper was cooking. He stood up from the cushion where he was sitting with his back up against the doorframe of the TARDIS. Jean finished her call and stood, too. She was used to ocean raft life now and easily stepped over the foot wide gap between rafts. Two comfortable mats made of woven water reeds were waiting for them at the supper table made of three thick layers of matting woven together.

Once they were seated, Sal, the raftman, passed them both cups made of large conical sea shells filled with a fermented drink made from the juice of the same reeds the mats were made from. It was stronger than wine but not as strong as brandy. They were both developing a liking for it as an aperitif. Sal’s wife, Dill, was preparing guma, which was boiled shoots of the SAME water reed, and looked and tasted like pasta flavoured with lettuce. Canice was the fruit of another sea-borne plant that was deep red and sliced up like a tomato but with the seeds on the outside like a strawberry. It didn’t taste like either, but its unique flavour was delightful. Dill put slices of canice on top of the platter full of guma and placed it on the table. They helped themselves to generous portions that they ate from plates made from the curved bones of a large fish and forks carved from the bones of a smaller one. After the ‘salad’ was finished everyone was served with a huge boiled crustacean rather like a lobster but with not so many legs. This was eaten with the fingers, cracking open the shell and enjoying the white meat inside.

Desert was sweetened canice on pancakes made from a rough flour ground from dried sea reeds, and there was both the heady fermented reed juice and a cool, sweetened, unfermented version to sip afterwards as they relaxed with full stomachs and contented minds in the dusk of a fine, warm evening.

After a week, Jean had stopped worrying about the fact that Sal and Dill were a race of humanoids who were pale blue, completely hairless and with webbed hands and feet as well as gills behind their ears that allowed them to swim underwater to gather the fruits of the ocean that they made into supper.

They didn’t seem to mind at all the two visitors who didn’t look anything like them and who needed to put on skin-hugging suits of rubbery fabric and strange metal contraptions on their backs in order to join them in the depths. The raft people wore ‘shifts’ made of cloth made from a sea plant that could be spun into thin, soft lengths of thread when dried. When they swam they discarded them, apparently having no concern about nudity when under water.

The reason they were not worried by their presence, Jean discovered, was that The Doctor was an old friend to the people of Ocean Blue. Sal had already mentioned meeting him and his friends when he was a small boy, and his father, Sol, had known him when he was in his youth. The impossibility of that didn’t bother them, nor the fact that The Doctor had looked different every time he visited this world.

After supper was a time for friends to gather. A half a dozen other couples crossed the closely gathered rafts from their peripatetic homes and settled by Sal’s brazier to drink fermented reed juice and talk.

One of the oldest of the group was Ido. He was father to strong sons and daughters and grandfather to a generation that were almost old enough to have children of their own. He was also the chief storyteller of this little community. After family gossip had been shared they looked to him for entertainment. He knew any number of fables about sea monsters that had been fought by raft dwellers of the past and love stories complicated by rivalry between one raft community and another.

The story tonight wasn’t a fable. It was a true story of what had happened when Ido was just a small boy, some eighty years ago. Jean listened in fascination to a tale about a stranger who came in a blue box, The Doctor with two young companions, a woman named Victoria and a boy named Jamie – her ancestor who had fought at the battle of Culloden. It had happened at this same time of year, autumn, when the people of the raft communities followed the strong currents directly towards the setting moon. The currents brought them to the warmer climate for the cold season when ice froze on the top of the sea.

But that year the current had been very strong. It was hard to keep the rafts together and there was disquiet among the people. Then The Doctor had discovered that they were all being dragged along with an artificial current created by a machine that was pumping water out of their ocean in order to fill the dried up seas of what had then been a red desert planet that reflected a deep orange coloured path to the horizon.

“But it is blue now,” Jean pointed out. “There must be water there?”

“Now, there is,” The Doctor answered before Ido completed the story of how he had saved the way of life of the raft dwellers of Ocean Blue as WELL as restoring the seas of its sister planet.

“And my ancestor, Jamie, helped you to do that?” Jean was impressed, and a little proud.

“He did,” The Doctor confirmed. “Jamie was a loyal friend. I wish you could have known him.”

The raft folk around the fire smiled warmly. They had all obviously heard the story more than once before. Jean wondered how much of it was literally true and how much was embellished by Ido, the born storyteller. The Doctor was giving nothing away on that count. His only contribution to the telling had been an impression of Jamie’s broad Highland accent that had been so startling to Ido’s young imagination.

He told another story before everyone started to feel sleepy – one that didn’t involve The Doctor. Jean let the story wash over her as she relaxed, mellowed by fermented reed juice and a seafood supper and the huge planet-moon in a star-filled sky. She was almost sleep-walking when they went back to the TARDIS raft and settled down for the night on their own sleep mats under that beautiful sky.

In the morning Jean woke to a very different sky and a heightened sense of excitement in the voices of the raft-people. The sky was pearly white and seemed lower than usual. It had been perfect blue from dawn to dusk every day since they arrived on the planet and she had taken it completely for granted, remembering only to cover her exposed pale Celtic skin with a high factor sunscreen every morning.

“It’s cloudy,” she said, sitting up and noticing The Doctor standing at the front of the raft looking towards a horizon obscured by white.

“It’s foggy,” he amended. “And interestingly I don’t think that’s JUST fog ahead of us.”

“You mean….” Jean recalled the last story that Ido had told last night. It was about a mythical landmass that was occasionally sighted by the raft people. It was said to be the birthplace of the birds that flew in the sky and perhaps the raft people themselves long ago, before they took to the ocean life. Jean had been too sleepy to give it much thought, but it had made a kind of sense. Dill and Sal had laughed, though, swearing that they had never seen the island in the mists and nor had anyone they knew. It had to be no more than a story.

“Yes,” The Doctor answered with a delighted smile. “I looked on the TARDIS monitor. There is land out there – at least fifteen square miles of it – an island.” He pointed to a place where the white fog was darker – a humped shape of something more solid than water vapour.

“An island in the middle of a fog bank,” Jean said, standing and coming to join The Doctor. “If there’s a great big wall there, and natives who worship some kind of huge beast kept behind it, let’s do ourselves a favour and leave it alone.”

The Doctor laughed. He had spent enough time on planet Earth to get the literary allusion.

“I thought of that,” he told her. “I already checked the levels of carbon-dioxide in the fog. It’s not the respiration of a giant ape.”

“Ok, then. Mysterious island here we come, then? I suppose we ARE going there?” She looked around at the other rafts. The strongest men were getting huge oars out and steering into the fastest part of the current that led them directly to the island.

“The people call it Oganuza,” The Doctor said nonchalantly. “Which, as you will have gathered listening to them talk, is one of the longest words in their vocabulary, and basically means ‘Shell Island.’”

“Because there are beaches covered in beautiful shells of long dead crustaceans or because a well known petroleum company copyrighted it?” Jean asked.

“Possibly because it is the shape of a huge shell,” The Doctor suggested. “If you use your imagination, as the raft people do, having very little else to think about on a mostly empty ocean.”

The island was becoming more clearly defined every minute as they moved towards it on the current. Jean started to notice a strange noise and realised it was waves breaking on a beach. Far more birds than had been seen before filled the air above the raft community.

Soon they could make out trees growing right down to the water’s edge and waterfalls tumbling down cliffs.

“It’s beautiful,” Jean said. “A little paradise island.”

“Yes,” The Doctor agreed. “Although I have never found a place called Paradise that lived up to its name. I’d be quite happy if this was an exception to that rule.”

Their raft was aided in its journey by the TARDIS which was agitating the current magnetically. It was inevitable that they would make landfall first. Jean knelt and looked down at the water, noting that it was still very deep even close to the island. It wasn’t like a coral atoll with fantastic shallows full of exciting marine life. The deep water ran nearly all the way to where the land started.

“It looks as if there is only the one low point with a beach,” The Doctor noted. “Everywhere else is steep cliff sides. But that’s all right. We can pull the rafts up into the safe harbour and some of us can explore.”

“As long as I’m included in the ‘some of us’,” Jean conceded. “None of the ‘man the hunter’ going off to explore while the women stay by the campfire minding the babies and cooking water reed soup.”

In fact there were a number of the younger women among the exploratory group that went ashore. The older men and the women with children to care for stayed on the moored rafts. The more adventurous youngsters were already discovering the joy of sandcastle building when the explorers set off up the one gentle slope to the top of the cliffs that rose up on either side.

At the top they looked out to sea. The mists were thinning as the sun rose. They could see a few lone rafts heading towards the island, joining the group on the beach. Then they got ready to push inland through the tangled jungle of trees and creeping vines. The Doctor had brought a collection of edged tools from the TARDIS, including a gleaming pair of curved blades that looked like they might have once belonged to Genghis Khan or one of his relatives. These were far better than sharpened fish bones for cutting through the vines and for opening up the thick rinds of glorious coloured fruits that they picked from the trees.

The new tastes delighted the raft-dwelling people. Jean enjoyed eating something that hadn’t been harvested from the bottom of the sea for once, too. They planned to bring up baskets later and collect more of these fruits. They would be a treat for everyone.

“Those look like Birds of Paradise,” Jean commented as their slashing and cutting disturbed a group of brightly coloured birds from their roosts among trees that grew fruits something like small watermelons. “Not that I’ve seen one close up, but I’ve watched all David Attenborough’s programmes. It’s more or less compulsory on Bute.”

“A very similar species, yes,” The Doctor agreed. “They must be more or less confined to the island.” He turned to Sal and Dill who walked just behind him, fascinated by all the new things they were seeing. “Did you ever catch anything other than gulls in your nets?”

Roast birds made a change from fish and they were caught in nets flown above the rafts like kites. Their feathers made pillows and cushions to sit on. They were mostly of the grey-white sort. Dill confirmed that they had never seen birds with iridescent red, blue, green and yellow feathers before.

“A micro-ecology,” The Doctor said, with just a touch of showing off about him. “Countless varieties of fruit, birds adapted to eating them, insect life not seen on the Ocean. There will surely be some kind of small mammals and possibly reptilian life, as well. I doubt there will be any larger mammals on such a small island. There would be paths through the jungle from their foraging.”

“You mean like this?” Dill asked, pointing to a very distinct path where something had regularly moved through the jungle, trampling the leaf litter and breaking the tops of saplings. It was something about shoulder height to the raft people, The Doctor judged.

“Perhaps a boar or….”

“The biggest bore around here is about six-foot-one and wearing a bow tie and braces in defiance of all sense of jungle dress,” Jean commented. But she didn’t mean it. The Doctor made David Attenborough look like an amateur. He had never set foot on this island before, but he understood everything about it.

Well, except for the nature of the mammals that had made that path through the jungle. When they came face to face with one of them everyone was startled. He was distinctly shorter than the raft people, as he had guessed, but he was the same pale blue colour and obviously related to them in some way.

The chief difference was that this land-living man didn’t have webbed hands. His feet may have been unwebbed, too, but they were covered in strips of grubby but hard-wearing animal skin to protect them on the forest floor. His unwebbed hands held a spear made of a length of wood and a flint head.

He wore a kind of robe or jerkin made of fur. Jean thought it looked exactly like the sort of thing Fred Flintstone and his friends wore in the cartoons – with one shoulder bare and the ragged ‘hem’ just below his knees.

He was as startled by the visitors as they were of him, but he lowered his spear and nodded to them. He turned and walked back a few steps, then looked back and beckoned.

“Well, it seems like he wants to welcome us,” The Doctor said. “All the same….”

He took the lead. If it was a trap and spears were thrown instead of lowered he would be ready to dodge them himself.

He was right about the camp. They emerged into a natural clearing where a half a dozen rough dwellings made of sticks, skins stretched across them for walls and boughs of a tree something like the banana loosely woven into a roof. Four small men with unwebbed hands stood watching the path while a group of women and children hunkered in the dwellings.

The Doctor stepped forward, urging his party to remain under cover for the moment. He held his arms out and his palms spread to show he had no weapons.

“I come in peace,” he promised in a soft, reassuring voice. “Do not be afraid. I am The Doctor. The… Doc…tor….” He pointed to himself as he spoke then waved towards the man they had startled.

“Arregg,” the man answered. The Doctor assumed that was his name, not an order to attack or an attempt to clear his throat.

“Pleased to meet you Arregg,” he said. “I’d like you to meet my friend, Jean.” He beckoned subtly to her. Jean stepped forward. As he hoped, the sight of her fascinated the natives. On his first visit to Ocean Blue Victoria had been the centre of attention among the raft-people. They had wanted to stroke her long blonde hair. These bald, blue jungle-dwellers did the same. Jean stood patiently as they reached and stroked her red-tinted tresses.

“This would make a really good advert for Wash and Go,” she whispered. “They’re fascinated.”

“Hair is unknown to them. But I think they understand we’re not a threat. Move further into the camp. Everyone else, leave your spears behind and come unarmed. We’re all going to be friends.”

The raft people did as he said. The jungle dwellers watched them almost as curiously as they watched The Doctor and Jean. Their differences were as startling as their similarities. Arregg and his friends touched the thin woven shifts worn by the raft people and put their hands over theirs, curious about the webbing between their fingers.

“Gibloo,” Arregg said eventually.

“Gibloo?” Sal responded curiously. “Wait… I think… Doctor… that sounds very similar to ‘gibling’ – an old word of ours meaning either ‘brother or sister’. I think he’s trying to say that we’re kin.”

The Doctor nodded. He tried a few other words of the raft people’s language. Arregg and his friends responded with a word that was similar. Then he began to use whole sentences to which they responded.

“Arregg’s language is simpler, with less grammatical structure,” he told Jean, who was wondering why she could understand the raft people but not the jungle tribe. “The TARDIS translator is having trouble accepting it as a variation, but I’m getting it now.”

So were the raft people, who began to talk more easily with their land-dwelling ‘kin’. Jean slowly started to understand it, too. She suspected it was something to do with that TARDIS translator starting to work subliminally on her mind.

They were talking about something the jungle tribe called ‘The River of Life’. They said it lay a little way from their camp. They gathered water for drinking from it. They offered the raft people water from jugs made of fired clay. They were surprised by the taste. They were used to distilling seawater and extracting the salt from it. The resulting liquid was flat and somewhat tasteless. This was cool and clear and fresh in a way they had never experienced. Jean tried some, too, and after a week of the distilled water and an even longer time drinking the water manufactured from hydrogen and oxygen that came out of the TARDIS taps, she thoroughly appreciated it.

“They should bottle it and sell it at five quid a litre,” she said. “It’s better than Evian.”

“I agree,” The Doctor added, tasting a sip in his mouth. “There are some interesting minerals in it.”

He returned the jar with a thank you in the tribal dialect and listened to what Arregg was telling Sal and Dill about the river. The tribe had never gone very far upriver. There was another tribe that were less friendly. His people avoided them whenever possible.

“Maybe we ought to turn back?” Jean suggested. “We don’t need to run into trouble.”

The Doctor bit his bottom lip thoughtfully. Of course he was intrigued by the island. He was also curious about the ‘River of Life.’ He especially wanted to know WHY it was called the ‘River of Life’.

But leading Sal and Dill and the others into danger wouldn’t be right. He couldn’t do that to satisfy his own curiosity.

“Doctor,” Sal said to him while he was struggling with his own inner voice telling him to curb his curiosity. “Arregg wishes to see our rafts and learn more about how we live on the sea. I think it is enough for us to have made contact with these people with whom we have common ancestry. If you wish to see more of the island, we will return to the beach with our new friends and wait for you.”

“That is an excellent idea,” The Doctor answered. “I will press on alone.”

Jean gave him a stern look. Even though she had been the first to suggest turning back, she had said that for the sake of Sal and Dill’s people. If he was determined to go on, she would share the risk.

“You must beware the Nea’s,” Arregg told them when their intentions became clear. “Stay away from their camp.”

“That’s the other tribe?” Jean asked. “Are they very fierce?”

Arregg was a little vague about it. All he could really say was that the Nea’s had always lived upriver and that they didn’t have anything to do with them.

“We’ll take them as we find them,” The Doctor said as he bid farewell to his friends. Jean walked at his side until they both ducked under a low branch at the entrance to another jungle path. This one soon widened out again at the edge of the river. It was obviously the one that ended in a waterfall at the cliffs. Downriver they could hear it rushing swiftly. But here it formed a wide, placid meander over a yellowish silt-laden bed.

The Doctor looked at the fish that swam in the water and confirmed they were something like a trout or salmon from Earth freshwater rivers – the sort that could also survive in salt water if they went too far downstream and tumbled over the falls.

“They probably do something impressive at spawning time,” he said. “Leaping back up the falls to get upriver.”

“Yeah, I’ve seen that sort of thing on the adverts for John West,” Jean answered. “Er… Doctor….”

She saw a reflected movement in the water and turned to look at the blue-skinned native who raised his spear towards them. The Doctor did the same as he had done with Arregg’s people, showing that he was unarmed and speaking in the older dialect. The native threw the spear at him. He dodged it easily and it landed in the river. Without his weapon the native turned and ran back into the jungle. The sounds of his feet crashing along the path could be heard for a while before the birds resumed their song.

“Did you notice the difference between that one and Arregg’s lot?” The Doctor asked Jean.

“I wasn’t really playing ‘comparisons’,” she pointed out. “Not when we were targets in the native javelin trials. But he was a lot grubbier. And his….” She paused. “I wasn’t exactly looking, you understand. Men who run around jungles in primitive underwear aren’t my thing. But it really wasn’t much more than a ‘flap’ covering his modesty.”

“Modesty wouldn’t be the issue,” The Doctor said. “Protecting vulnerable body parts from the stingy, spiky, thorny parts of plants that grow about waist high would be the object of the exercise.”

“He probably has mates,” Jean pointed out. “Shall we get moving before they come back?”

“Let’s do that,” The Doctor agreed. He followed the river upstream, Jean following him. They heard sounds of men coming through the jungle behind them. The Doctor looked around quickly then leaped agilely at a rough-barked tree with thick, overhanging branches. He reached down to help Jean join him in the tree and they waited, keeping very still and quiet. It wasn’t long before a half dozen men dressed in animal skin ‘flaps’ passed underneath them. They were obviously on the look-out for them, but fortunately they didn’t expect to see them in the trees.

“There’s something sitting on my head,” Jean whispered.

“It’s a sort of squirrel,” The Doctor answered her. “Or a possum, a racoon.... Just keep still. It won’t be interested in eating you. It will be a vegetarian.”

“It’s looking for vegetables in my hair,” Jean said.

“Hush, I think the hunting party is coming back.”

Jean kept very still and quiet, trying not to worry about the small paws with needle-sharp claws that were scrabbling around her skull. She watched the natives pass under the tree again, this time with a creature something like a wild boar suspended from two spears.

“They’ve got food. They won’t be worried about us, now,” The Doctor said once the sound of their shuffling feet on the jungle floor had receded. “We’re ok to carry on, now.”

Jean shook her head slowly and the squirrel-possum-racoon leapt further up the tree. She swung down from the branch and did her best to re-arrange her hair while The Doctor again took the lead in their trek.

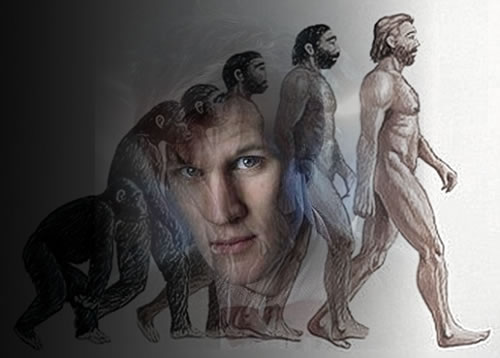

“Nea,” The Doctor said as they walked. “That’s what Arreg called them. I wonder… something like Neanderthal? They had much more pronounced foreheads than Arreg’s lot. They were a less advanced species.”

“Is that possible?” Jean asked. “I mean, didn’t Neanderthals exist BEFORE what we think of as ‘modern man’ on Earth?”

“More likely the two co-existed for a long time,” The Doctor replied. “Overlapping. But the more advanced evolutionary form was better adapted to survive. His communication skills, use of tools and so on allowed him to prosper.”

“Obviously Arregg’s lot avoid them. They’re not going to mix the genes.”

“Quite so,” The Doctor agreed.

They walked on, seeing one of the boar-like creatures running away into the jungle and smaller animals scampering along the ground or along tree branches. The Doctor spent a lot of time looking into the river.

“Haven’t you had enough of fish this week?” Jean asked him.

“I wasn’t considering these for lunch,” The Doctor answered. “I was more interested in their evolutionary development. These ones have less well developed fins than the trout-like ones lower down the river. They would NEVER be able to leap back up the falls for spawning. Their eyes are less well-developed, too. I should think they’re almost completely blind.”

“Ok,” Jean said, accepting that as a fact but not connecting it to anything important. They went on walking until they came to another clearing by the river side. It was narrower but deeper and faster here. The Doctor halted at the edge of the undergrowth and hunkered down. Jean did the same as they watched another group of blue people by the riverbank.

They were catching fish in much the same way that bears in the wilds of Canada and North America were known to catch them, thrusting their arms into the water and throwing the fish up onto the river bank. There, the fish were killed by a blow with a rock and eaten.

“They’re eating them raw,” Jean pointed out, trying not to be squeamish about it. “They’re….”

“Even less advanced than the Nea,” The Doctor said. “They’re all quite naked, male and female.”

“I was trying not to notice that,” Jean pointed out.

“It wouldn’t bother them. They don’t know that nakedness is unfashionable. Their language is… non-existent. They’re several levels of intellectual development behind out raft-dwelling friends or Arregg’s hunter-gatherer tribe.”

After they had eaten their fill of the fish the group of primitives scampered away into the jungle again. Scampered was the most accurate description of their gait when they moved. Jean was reminded of chimpanzees, and she realised they were about the same height as a chimp, too. Without the other tribes to compare them with she hadn’t really thought about it.

“Sal’s lot were taller than Arregg’s tribe, and much more straight-backed. Arregg’s group were taller than the boar-hunters. They didn’t bend down as much on the paths. This lot are even shorter.”

“Evolutionary progression,” The Doctor said. “Look.”

He was examining the remains of the fish left behind on the river bank. Jean preferred not to. It was a rather gory mess.

“These have no fins at all. They’re more like eels. Blind eels at that.”

“Doctor, are you saying that the fish are at different evolutionary levels as they go downriver?” Jean asked.

“Yes, I am,” The Doctor replied. “And so are the mammals. Your friendly squirrel has given way to something much smaller and less well adapted as we’ve progressed. They don’t have the dexterity of their front paws or the front teeth that can crack nutshells. They would be dependent on softer fruits grown closer to the ground, and they wouldn’t have the ability to gather and store food for winter.”

“So….”

“So, what was it you were saying earlier about David Attenborough?”

“His brother – you know, Richard, the acting one - owns a house and a huge chunk of land on Bute,” Jean answered. “David regularly comes up to look at our bird colonies. They’re both regarded as local celebs.”

“David would REALLY love this island,” The Doctor said.

“Yeah, he would,” Jean agreed. “It’s like one of his series’ all rolled into one afternoon ramble.” Something by the riverside caught her eye as she thought about all the natural history she had ever watched on TV and then thought about all of the planets she had visited where the rules were all rewritten. “What’s that?”

The Doctor scrambled down the river bank and pulled the pearly grey object closer. It looked, at first glance, like a really large half coconut shell. Then she realised it was something like a coracle – a primitive man-made boat constructed from woven twigs. He pulled something out of it. Jean realised with a sinking heart that it was a body.

“One of Arregg’s people,” he said. “I didn’t know they’d started exploring the river by boat.”

“What killed him?” Jean asked. “Did the primitives attack him?”

“No,” The Doctor answered after examining the body carefully with the sonic screwdriver. “It was natural causes. He died of acute appendicitis. Poor man. He must have been in such pain. He couldn’t even row himself back downstream to be with his own kind at the end.”

As he spoke, he was piling dry leaves and twigs around the body, then larger boughs of wood. When it was covered, he used the sonic screwdriver to create sparks that set the dry leaves alight. Soon the funeral pyre was thoroughly burning.

“Come on,” he said. “The smoke will attract the primitives. We’ll take the coracle.”

“We will?” He was already settling himself down in the curious little craft and experimenting with the crude but effective paddle. Jean stepped aboard and tried to make herself comfortable. The Doctor pushed off from the bank and paddled strongly against the current. They moved at a surprising pace away from the smoke that rose up into the sky and the sounds of the raw fish eaters coming to find out what had happened.

The river narrowed and quickened as it reached its ‘younger’ phase. The Doctor still managed to paddle against the flow. Jean wasn’t surprised by that. Beneath his rather absurd physical appearance was a strength that could be under-estimated by those who didn’t know him. Jean thought that nobody would ever really fully know The Doctor, but she was one of the few who had been allowed to glimpse into his depths. The fact that he could paddle a primitive coracle upriver didn’t surprise her one little bit.

The river, however, offered plenty of surprises of their own. Jean looked into the water and noticed that the fish were becoming more and more simple, unevolved. Even the eels gave way to a sort of completely blind worm-like creature that wriggled along in the undercurrent. Then even they disappeared and she saw something that, at first glance, looked like over-cooked pasta shells before she recalled seeing images of the creatures that were found around hot water geysers in volcanic parts of the Pacific Ocean bed. They were very much like those very basic lifeforms that evolved in that very specific ecosystem.

And a little further upstream there didn’t seem to be anything living in the water at all.

“Not to the naked eye,” The Doctor explained. “There is life there, but microscopic zooplankton and single cell amoebae.”

Then he pushed the coracle to the edge and climbed out, reaching for Jean’s hand. They were in very different territory now. The jungle was below them and they were walking on a dry grass that grew to around ankle height. Clearly there were no animals large enough to graze upon it. There didn’t seem to be any animals at all, not even birds. There were insects buzzing around in the grass, but nothing bigger.

“Where are we going?” Jean asked.

“There,” The Doctor answered, pointing to a curious feature in what had to be the centre of the plain. It looked very much like the geysers that she had been thinking of earlier, except much bigger. The water that spurted up out of the ground every few minutes rose as much as a hundred metres into the air, most of it falling back and feeding the river that flowed down through the jungle, passing those three distinct tribes of people and eventually tumbling over the cliff into the ocean.

Some of it evaporated and formed the clouds that sometimes lay so low that it covered the island with mist. That mystery was solved, at least.

“It wasn’t the respiration of a great big monkey,” Jean acknowledged as they drew close to the edge of the geyser. It wasn’t hot water, she noted, just slightly warm. It was slightly cloudy, unlike the crystal clear, cool water further downriver. “It must have a lot of minerals dissolved in it?”

The Doctor didn’t answer. He just smiled. He put his hand in the water then touched his finger with his tongue. For a moment he was thoughtful. Then he used the sonic screwdriver to analyse the water more thoroughly. When the spout of water subsided He knelt and looked down into the shaft. “Yes, of course. I understand it all, now.”

“Understand what?” Jean asked. The Doctor’s smile broadened to a familiar grin.

“The River of Life – it really is exactly that. Life begins here… as a soup of amino acids, the building blocks of carbon-based organisms. You saw the progression as we came upriver – amoeba to zooplankton, to complex organisms, to blindworms, eels, to fish as you know them. On land, the animals develop in much the same way. Your squirrel-racoon is part of the progression. So is the wild boar. So are the fish-eating primitives and the Nea, and Arregg’s tribe of tool-using hunter-gathers. And so are Sal and Dill and all their friends whose ancestors left the landmass and set off to sea.”

“Wow,” Jean said. She felt she had to. It was an incredible concept – all those stages of evolutionary development in one place at the same time. It deserved a ‘wow’.

But The Doctor wasn’t finished.

“I’ll explain what else I’ve found out when we get back to the beach,” he said. “I think the others will want to know what I know.” He grinned again and headed back to where he left the coracle. “It’ll be easier going back – paddling with the stream.”

Actually, he didn’t really need to paddle very much. It was really just a matter of steering. The current was strong enough, even in the slow, meandering part where they kept their heads down and did their best not to be noticed by the Nea’s. Fortunately the tribe were too busy enjoying their wild boar roast to watch the river.

Further on the current picked up speed again. Jean pointed out the place where they had first picked up the path along the river bank, but they were going too fast to stop.

“Doctor… the WATERFALL!”

It was too late to do anything about that, either. Jean screamed as the coracle tipped over the edge and they fell with it. She closed her mouth and stopped screaming just before she plunged into the sea.

When she came up to the surface again she gasped for air and then struck out for the beach. Sal and his friends, as well as Arregg and some of his tribe were there. They had a brazier lit and were cooking fish and steaks – a feast for the land and sea tribes. They had all witnessed The Doctor and Jean’s unexpected return and were ready to greet them as they emerged from the sea.

“Next time….” Jean said to him through chattering teeth as she sat by the fire and warmed herself. “Next time…. No, forget it. There won’t BE a next time. I am NEVER getting into any form of boat with YOU,” she told The Doctor.

“You loved it,” he answered. “You know you did.” Then he accepted a cup of something hot that tasted a little like nettle tea. So did Jean. By the time they had drunk it the food was cooked. The two tribes gathered as one to eat and to talk, and afterwards, in the fast approaching dusk, they were ready to tell stories to each other.

“I have one that will interest you all,” The Doctor said. “About a mysterious island that the people of the ocean didn’t believe existed - the reason being that it could not be fixed in any location. And the reason for that is that the island is as peripatetic as they are. It isn’t, in fact, an island. It isn’t a land mass rising up from the sea bed, or a coral reef that has grown above the surface of the water. It is actually floating – in fact, it’s swimming on the top of the ocean.”

“Swimming?”

“This island – Shell Island, is named so because it actually is the shell of a great sea turtle – a living creature.”

“WHAT?” Jean couldn’t help her exclamation. The sea people were surprised, too. The land tribe less so.

“You knew, didn’t you?” The Doctor said to Arregg. “Your people have always known. Perhaps at night, when all is quiet, you can even hear the creature’s heartbeat, sense its sluggish reptile blood pumping around its body. You know that your floating island doesn’t just drift on the tides. It moves with the seasons, always keeping within the warm climate. Turtles don’t care for the cold. You live in a tropical paradise all year round because of it.”

“Yes,” Arregg confirmed. “We have always known of it.”

“A turtle fifteen miles wide?” Jean queried.

“Fifteen square miles in surface area,” The Doctor corrected her. “Yes. Even on Earth specimens of the superfamily group Testudinoidea are known to live long lives and some grow to immense sizes. This is an extreme example.”

“Wow,” Jean said, deciding that this was a ‘wow’ kind of moment once again. Considering that she had spent a week on an ocean planet with a tribe of pale blue people with webbed feet it had to be quite a special day to produce two ‘wow’ moments.

It was only later, when the night had fallen gently and the two tribes and their friends were settling to sleep together on the beach, that Jean remembered another question she needed to ask in the wake of those revelations about Shell Island.

“What about the geyser, then?”

“That’s unusual,” The Doctor admitted. “It seems that the species of really gigantic turtles of Ocean Blue have a blowhole in the middle of their shells much like cetaceans with which to expel excess liquid from their bodies.”

“You mean whales?” Jean thought about it. Then she listened to the sound of the waterfall above the gentle sound of the waves on the shore. “Doctor, are you telling me that that river is – basically – turtle wee?”

“I wouldn’t have put it exactly in those terms. But, yes.”

Jean wondered what she could actually say in response to that. Only one thought came to her mind.

“David Attenborough REALLY ought to know about this place.”

|

|

|