Rodan walked between Marion and Kristoph along the wide pavement of Lime Street. She insisted on walking rather than being carried. She wanted to show off her new cloak that covered her velvet and lace dress and her new shoes. Marion wore a similar cloak that kept her warm on what was a bitingly cold evening in December. The pavement was free of snow. So was the road itself, but dirty drifts of it piled up in the gutters. They kept close to the front façade of Lime Street station as a carriage went by, its wheels making some of that grubby snow fly up. Marion smiled nostalgically at the sight of the elegant lady and gentleman in the Brougham. She was quite used to travelling in horse drawn carriages herself when they visited Ventura IV where they were the popular means of transport even though it was a technologically advanced society.

Liverpool in 1896 wasn’t technologically advanced, but the journey from the railway station where they had left the TARDIS to the Empire Theatre was hardly worth the bother of a cab. They walked, taking in a different view of Liverpool than she was used to. St. George’s Hall, of course, hadn’t changed a bit. Nor had the front of the railway station itself. But all the modern buildings she knew, like the Radio City Tower or Queens Street bus station and St. John’s shopping centre were about seventy years away in the future. The lamps that lit Lime Street were some of the earliest electric street lights in Britain, but they were obviously converted from the old wrought iron gas lamps and it was a darker street than she knew in her own day.

The newly opened Empire Theatre, formerly the Royal Alexandra Theatre and Opera House, had the new-fangled electricity, too, and looked bright and welcoming. Marion noticed that the couple in the Brougham had alighted there and were entering the foyer in front of them.

“Pretty,” Rodan commented. She didn’t mean the plush velvet curtains and gilded mouldings and the glittering chandelier overhead. She was used to all of that in Mount Lœng House. She meant the ladies in dresses with wide, flowing skirts who stood chatting with the men in evening dresses. There were children, too, dressed in smaller and simpler versions of the adult clothes. There were a few people of high quality, of course, the ones who arrived in the broughams and landaus. There were also the affluent middle classes who lived in the comfortable villas in the new suburbs of Liverpool and came into the city in their finery. The difference in class was obvious not only because they walked from the railway station but in the less glittering jewellery and less finely tailored suits on the men.

Some of the theatre goers were clearly better off working class people in clothes that tried to emulate the higher born ladies and gents in cheaper fabrics, muslin rather than silk or satin, cotton rather than velvet brocade. They shone a little less in the chandelier light but they were happy and excited to be enjoying an evening at the theatre.

Nothing had changed, really, Marion thought as she noted these social demarcations. There were the high fashions and designer labels, there was Marks and Spensers and there was Primark!

There were some even less well dressed than that. A whole group of young girls and boys, aged between nine and twelve who put Marion in mind of that line from A Christmas Carol “a twice-turned gown, but brave in ribbons, which are cheap and make a goodly show for sixpence.” She noticed that the ladies of quality shuffled out of the way as the ‘orphans’ and their housemaster and mistress passed through the foyer and through the door to the cheaper stall seats. They were rushed past the little kiosk where boxes of sweets and chocolates were sold to the theatre patrons, but Marion noticed that each child was holding a shiny red apple and what looked like a piece of gingerbread. They had their own little sweet treats for the performance and when Kristoph purchased a big box of expensive hand made chocolates for her and Rodan to share she didn’t feel too guilty.

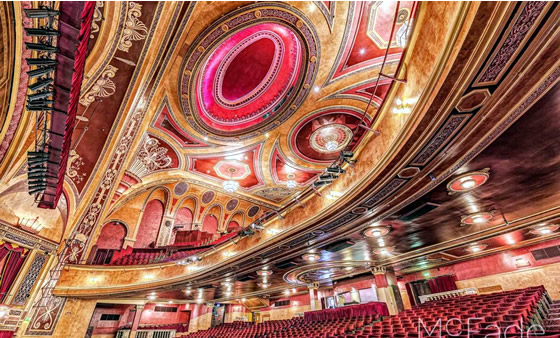

This wasn’t the Empire Theatre she knew from the 1990s, of course. That was only built in the 1920s. This one dated from 1866, and had been newly refurbished this year in time for the Christmas Pantomime. In addition to the stalls where the less affluent could sit there was a curving dress circle balcony and also a number of boxes with gilding and moulded plaster decorations and plush curtains.

Kristoph, of course, had made sure they had a box. And it was one of the best ones, too, overlooking the orchestra pit and with the very best view of the stage. The box opposite, in fact, was occupied by the Lord Mayor of Liverpool and his family.

“We’re causing a bit of gossip,” Kristoph told Marion as she opened the box of chocolates and let Rodan take one for herself. “Everyone is wondering who we are – people of quality in the finest clothes and the best of the boxes.”

“Lord and Lady de Lœngbærrow of southern Gallifrey!” Marion said with a laugh. “Or Lady Marion of Birkenhead!”

“Lord Kristoph and Lady Marion of Birkenhead,” Kristoph told her. “And the honourable Rodan!”

Rodan didn’t look very honourable with chocolate all over her face. Marion found a packet of anachronistic but very handy moist wipes and cleaned her up. Since she gave her another chocolate straight after it was a wasted effort, of course.

The house lights went down and the orchestra began the overture to what was a very noted stage adaptation of the story of Cinderella, produced by one Mr Oscar Barrett, a famous theatre impresario. Some of the actors on the stage were celebrities of the time, especially the lady playing Cinderella herself. The production was quite a coup for the new management and the newly refurbished theatre. It was the equivalent of…

Marion smiled as she remembered her local history. The new Empire Theatre that replaced this one in the 1920s was the venue, in 1965, for the last Liverpool gig by the Beatles, when they had become famous enough to need a bigger venue than the Cavern. This was the same sort of big night for 1896.

The performance was exciting for young and old. Rodan forgot about the chocolates as she watched the colourful, bright action on stage and listened to the singing accompanied by the orchestra. Marion forgot about the chocolates, too, as she became engrossed in the performance. It was before the era of microphones and surround sound theatre, of course. The actors had to project themselves to the very back seats and up to the Circle and the upper level of boxes. There was, therefore, not much in the way of subtlety in the acting. But then, it was pantomime. Subtlety had never been called for. Bold gestures, loud acclamations, knockabout comedy, were what the audience wanted and just what they got. The ballroom scene with Cinderella capturing the prince’s heart was a spectacle of big, flouncy dresses.

Marion smiled her own smile as she watched the familiar story unfold. Her own story had been a bit of a Cinderella one, after all. She had come from a poor home, struggling to make her way in life, and she had met her own prince charming. He hadn’t exactly looked like a prince when she saw him in that waiting room on Leeds station in his tweed suit that made him look such an archetypical teacher. He looked more the part now in his evening suit of fine silk and an embroidered waistcoat beneath. Those who surmised that he was some titled gentleman patronising the Empire were not far wrong. He just wasn’t mentioned in the peerages of the British Empire. He was a prince of the universe, and there was nothing higher than that.

She glanced at Rodan as she watched the pantomime from her own seat, between her foster parents. She was enjoying the colourful pageantry, but she also seemed to be taking in the story.

Marion wondered if Rodan would ever meet her own handsome prince? What was her future? She was, after all, a Caretaker child. When she went to live with her grandfather, she would live a Caretaker life, receiving the education of one born to serve the aristocrats of Gallifrey. She could end up returning to Mount Lœng House as a servant. That was a sad prospect for her. And what chance would she have then to wear velvet dresses and be treated as she ought to be treated.

On stage, Cinderella was dancing with the prince and the chorus was getting ready for the finale. In fiction, at least, happy endings were given to the deserving, and just desserts to the undeserving. Marion allowed the fun of it to carry her along until the last curtain call. But the thoughts she had harboured for a while came back to her as the house lights went up and they prepared to leave their seats. Kristoph picked Rodan up and carried her in his arms. She was sleepy now and didn’t want to walk. Marion brought the remains of the box of chocolates and the souvenir programme and walked at his side.

“Marion,” Kristoph said quietly. “Rodan will never be a house servant for us – or for any family on Gallifrey. That much I will make certain. There ARE other careers for Caretaker girls, and whatever she proves to have a talent for when she is older, I will make sure she has the opportunity to pursue it, whether it be dressmaking like Rosanda, or ice skating, piano playing, or if she has what it takes to succeed in the civil service or some other office of the government. But she will be raised as a Caretaker, by her grandfather. That is the right and proper thing.”

“I understand,” Marion said. “But…”

“Whether she will meet a prince charming….” Kristoph smiled as he caught her thoughts. “Fairy tales do come true sometimes. My dear mother is an example. She certainly won her prince’s heart. So did Rika when my brother fell in love with her. And you, my dear Cinderella of Birkenhead.”

“But that doesn’t usually happen on Gallifrey,” Marion pointed out.

“It happens even less on planet Earth,” Kristoph countered. “How many women of low birth have you heard of who married princes?”

“Anne Boleyn, Grace Kelly and Lady Diana,” Marion admitted after a moment’s thought.

“And it hardly turned out a happy ending for two of those,” Kristoph pointed out. “But it doesn’t have to be a fairy tale for it to be true love. Ask Rosanda next time the two of you are talking about dressmaking fabrics. Do you think she felt any less happy than you when she married Caolin? Did he seem any less a prince charming to her as I did to you? He is the man she loves and she is as happy as you or Rika or my mother, or as Calliope was when she married Jarod. And as long as our little fosterling meets a man as honourable as our family butler I shall certainly bless their union.”

“I just want the best for her,” Marion told him.

“And she will get what’s best for her. And best for her could turn out to be a good man of her own class and a circle of friends who will always treat her as an equal, rather than struggling to be accepted by the snobs of Gallifreyan high society.”

He was right, of course. And Marion wondered if she, herself, was being snobbish in wanted more than that for Rodan. After all, she always told people that she loved Kristoph before she knew he was a lord, that it was not his position and wealth that mattered to her.

“After we’ve put our little fosterling to rest in the TARDIS, I think a little light supper for the two of us. Then I will programme our journey home while we sleep. Tomorrow, of course, you will be up at dawn preparing for our ‘traditional’ Christmas banquet and putting presents around the tree for Rodan to open. If there is a single toy in the universe she doesn’t have already.”

“She will by the day after tomorrow when she opens them all. I can’t wait to see her face when she sets eyes on the puppet theatre and the dolls house.”

“That is worth looking forward to. But… before then…” Kristoph smiled grimly. “Those youngsters who came to the pantomime with their apples and gingerbread. They’re from what was called in these times an Industrial School. An orphanage, but also a place where they work long hours, training them for domestic service or, at best, a shop apprenticeship. They have clean clothes and a bed, and food of a sort. It’s not a workhouse of the dreadful sort you would think of. But love is in short supply, and so are treats such as better off youngsters might take for granted. I think we should spread some Christmas cheer among them. Suppose I arrange for some hampers of festive food to be delivered to the School, from a ‘benefactor’?”

“Yes, please do that,” Marion said. “And… thank you, Kristoph. For being such a kind, generous man. That’s what I love about you most. Not that you’re a lord, and enormously rich. Because you’re so kind. That’s what I have always loved about you.”

They stepped out of the foyer of the Liverpool Empire Theatre and their well-shoed feet crunched on a fresh, clean fall of snow. Marion looked around at the familiar and yet unfamiliar Lime Street. It looked like a scene from a traditional Christmas card, the sort she never believed could be entirely true. She sighed happily.

“Merry Christmas,” she whispered to her husband.

“Merry Christmas to you, my dear,” he answered.

|

|

|