On the day the exam results came out Kristoph drove Marion up to Edgehill College, on the outskirts of Ormskirk. He waited while she went into the office to get the envelope she had set so much store by. He was surprised when she returned to find the envelope unopened.

“Not yet,” she said. “Let’s go and meet Li.”

They met Li at his favourite Chinatown restaurant, where respect for him as a venerable old person of their community meant that he got the best table. He WAS, of course, a very venerable and very old member of the Chinese community. Having lived there for more than 4,000 years before Communism disgusted him so much he abandoned it for the exile community, he certainly qualified as a Chinaman, even if he was not actually born there.

They drank rice wine while waiting for their food and at last Marion opened the envelope. She tried to be cool about it and reveal the result to the two men slowly, but the smile on her face gave her away.

“I passed!” she said. “I’m…. I’m a TEACHER.”

“You passed with a final result of ninety-six per cent,” Kristoph said, reading the slip of typed paper. “Congratulations, my dear. You are going to be an EXCEPTIONAL teacher.”

“A noble career,” Li told her. “And I applaud your aim to teach the less favoured of my own race. A noble career, indeed.”

“You know,” Kristoph pointed out. “You didn’t NEED to be qualified to do that. My family OWN the school.”

“I needed it for me, so that I knew I WAS qualified and capable. And I HAVE learnt a lot this past year that will help me to be the sort of teacher they deserve.”

“I know that,” Kristoph conceded. “And I AM proud of you.”

“It means you will leave, soon,” Li pointed out. “I will miss you, both. My dearest friends.”

“Next week,” Marion said. “We have made all the arrangements. We’re giving the house to Mrs Flannery. She has been Kristoph’s housekeeper ever since he came to Liverpool. And we think it might be hard for her to get a new position at her age. The house will set her up. She can sell it or live in it if she likes.”

“A generous offer,” Li agreed.

“We haven’t told her yet,” Kristoph added. “We expect her to need oxygen when we give her the deeds.”

“I’m glad the house is going to somebody who deserves it,” Marion said. “It’s strange when we come this close to leaving, how little we are taking with us. Only some books and music and personal things. And yet there is nothing much that I feel I am leaving behind.

Except the planet, she thought to herself. Except everything she knew and was familiar with. In the past weeks as the day of their departure grew closer she had become so aware of little things that she took for granted, that she knew she would not have any more.

Yesterday had been an example of the strange panic that took her. She had been at Tescos, buying food for the week that was left. She had looked at things like Kellogs cornflakes and McVities chocolate digestives and Heinz baked beans and her heart seemed to flutter. She had the sudden urge to buy as many of the branded foods she knew so well as possible. Nescafe and PG Tips tea went into the trolley along with those other things. Packets of toothpaste, chocolate, custard powder, all sorts of things that she felt she would never see again after next week. She brought them out to the car where Kristoph was waiting, and then went back in and bought another trolley full. When she wanted to go again Kristoph had put his foot down firmly.

“Enough,” he had insisted. “You’ll have the staff thinking you’re trying to open a corner shop with their stock. And what will Mrs Flannery think?”

“She’ll think I’m taking some home comforts to Rumania, so I won’t be homesick,” Marion answered. “And it will almost be true. Only we’re going much further than Rumania.”

“You really think that on Gallifrey you will need plate of spaghetti hoops to make you feel less homesick?” Kristoph asked her when he related the story to Li and both gently laughed at her.

“Yes,” Marion insisted. “I think I might, sometimes. And don’t tease me, either of you. It’s not fair.”

“No, it isn’t,” Li agreed. “Let her have her comforts, my friend. You and I both know the wrench of exile. If we had some equivalent to spaghetti hoops and cornflakes and tea bags to comfort either of us we would have been happier men.”

“Wasn’t there anything you wanted to bring?” Marion asked them both.

“I left in something of a hurry,” Li reminded her. “But I did have one thing. A cutting from Lady Lily’s rose garden. It grew in my TARDIS when I was fleeing across the universe and when I settled in China, I planted it there. A descendent of it is growing in my garden here in Liverpool now. a rose that began on our home planet.”

“I just brought the memory of home,” Kristoph said. “I found the better part of me here on this planet. My Earth Child.”

Marion smiled at the sweet compliment. For her, home was where Kristoph was. And he needed to go home to Gallifrey. So she would be at his side. Nothing else mattered.

Still, the leaving was hard. Much of her last week on Earth was spent in places she wanted to see one more time.

One of them was on the other side of the Mersey. She travelled there not by TARDIS or by car, but by the ferry. Kristoph and Li both came with her.

“All the years I’ve lived here I never took this trip,” Kristoph admitted as they waited at Pierhead to board the little boat. Marion talked about how she loved it as a child, feeling when the ferry was in the middle of the wide river estuary as if she was out at sea on a real voyage, even when it was just a 50p triangle trip Between Seacombe and Woodside and Pierhead on the other side.

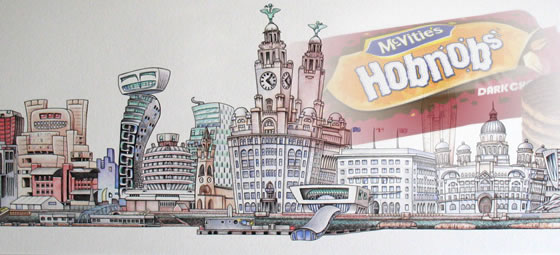

Soon she was going on the longest and greatest voyage of her life. But for now she was content to sit on the top deck of the ferryboat and savour the salty air of the Mersey blowing her hair back as she looked at the familiar skyline of Liverpool on one side and Birkenhead and Wallasey on the other, her home for all of her life so far.

The original plan had been to get off the ferry at Woodside and go and look at the place where she was born and grew up. But when the ferry reached the Woodside landing point she hesitated.

“I don’t need to see it,” she said. “There’s nothing left there but empty memories. I don’t even have a grave to visit. Mum and my grandparents were all cremated over on the other side at Anfield Crematorium. There’s nothing but a house that belongs to somebody else now.” She sighed and leaned on the rail and looked at Birkenhead. “There IS nothing for me here. I may as well go to another planet. Nobody will miss me.”

“I will miss you,” Li told her. “I shall look forward to you coming back to visit me and treasure the moments.”

“I wish you could visit me,” she answered. “Perhaps they will relent and let you come home.”

“Perhaps,” he said. “But if not, I have made this planet my home and made my own happiness. Just as you will make yours on Gallifrey.”

Li and Kristoph both held her hands tightly as the ferry set off again, back across the Mersey to Liverpool. She had needed to come on this trip, just for the afternoon, just to see, to say goodbye. And she had done that. She felt a lump in her throat as the ferry boat came back towards Pierhead and the song “Ferry Across The Mersey” was played over the PA system that had relayed a historical commentary throughout the journey. But it was only a moment of emotionalism and it passed as they stepped off the ferry. They walked up to the promenade above and stood for a moment looking out over the river to the place they had just been.

“This is where immigrants used to set off from, leaving Liverpool for America and Canada, and for Australia,” Marion said. “People have been leaving Liverpool for a long time. I’m not the first. I won’t be the last. But I will be the first to leave it for Gallifrey.”

There were some other places she wanted to visit. They took the transpennine train one day all the way to Whitby and watched the sun go down in the place where they first kissed and kept on kissing until the sun came up again. On the way back they stopped off in Knaresborough and made a new wish at the well.

And that was about it. The morning after their trip to North Yorkshire Kristoph called Mrs Flannery into his study and presented her with the deeds to the house. She didn’t quite need oxygen, but she did burst into tears and used half a box of tissues before going to make tea for her former employers now her overnight tenants, who spent a quiet evening listening to music on the stereo before taking an early night.

The next morning, early, they got up and dressed and ate breakfast and tidied the dishes away afterwards. Then Kristoph picked up the two last bags of luggage and brought them to the TARDIS. Marion’s bag included a fresh packet of tea to be used as soon as she got to Gallifrey.

“Shall we take it slow for the first lap?” Kristoph said as she sat on the sofa and he went to the console. “Gently through the solar system.”

“Yes,” she said. “Please. He pressed the dematerialisation switch. Moments later they were in space. Marion watched with only a little sadness on her heart as they slowly moved away from Earth, the planet of her birth and towards an uncertain but exciting future. Kristoph stayed at the console until they were through the asteroid belt and then came to sit by her. The rest of the course was preset.

After they had left the solar system behind the TARDIS would enter the vortex and they would cross the galaxy in a day. They would reach Gallifrey in time for breakfast tomorrow.

|

|

|