The TARDIS was in its usual place beside the recreation ground with a block of unprepossessing council flats for a background. The three people who sometimes allowed themselves to be called Team TARDIS all grinned and stepped forward as the door of the 1960s Police Box swung inwards to reveal a much bigger space than the human imagination should have encompassed.

“Hey, Doc, what are you wearing?” Ryan asked. The eclectic mix of jumper, culottes, braces and boots had been replaced by a light khaki coloured blouse and ankle length skirt with a wide-brimmed pith helmet.

She looked like a lady archaeologist from a 1930s desert expedition.

“The Wardrobe will have stuff for all of you, too,” The Doctor said as she reached for the door mechanism and then initiated a dematerialisation. “We’re joining a 1930s archaeological expedition in Mesopotamia.”

It took a little over half an hour for the three of them to choose and change into clothing to match The Doctor’s attire. Ryan wore a grey linen suit with open necked shirt and a homburg hat. Graham was in a similar suit but with a necktie and a narrow-brimmed pith hat. Yasmin chose something like The Doctor’s outfit but with breeches instead of a skirt and a mosquito net that came over her eyes fixed to the brim of the hat.

In little less than an hour since leaving drizzly Sheffield, they had parked the TARDIS in the freight yard of Mosul railway station in the dry heat of a late afternoon. They had been collected in a soft-topped truck of indeterminate make by a Frenchman called Jean-Claude Lefauvre who was, The Doctor explained, chief driver and quartermaster of Max Devine’s expedition.

The front passenger seat which might have been relatively comfortable, given that the ‘road’ was a single lane of ruts and potholes, was occupied by a box of carefully packed bottles of liquor which was getting the VIP treatment because it was more fragile than people, and apparently more valuable. Team TARDIS were wedged in the back seat by a collection of parcels, a bag of letters and a sack of flour. The latter, Graham thought, might just do the work of an airbag in the event of an accident.

“When you said Mesopotamia, I had forgotten that was an old name for part of Iraq,” Yasmin commented as they left the city behind them for the desert. “That’s a country I never thought I’d visit. Mosul… I’ve only seen it on the news… as piles of rubble and devastation. Driving through it just now… It looked quite… nice. The markets and the big mosque, and the river….”

“It’s a shame,” Graham agreed, recalling that trains went from the station to Basra and Bagdad, two more places they had only ever associated with war. “The place is quiet enough now, though, isn’t it, Boss?”

“The Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq was founded three years ago when yet another British diplomat drew pencil lines on a map,” The Doctor said. “Eventually that will be the cause of problems, but at this time things are steady enough for the desert to be knee deep in European archaeologists digging up the past.”

“Like this Max pal of yours?” Ryan asked.

“Just like Max. I joined the dig at Nineveh last season. I said I would bring some friends to help at the new site. Max thinks it might be a previously unknown Akkadian Empire settlement. It’s about eight miles north of Mosul by road, twelve by river. Tel Kayifa is, apparently, rather a nice spot by the Tigris, all fig trees and shady places to rest between the hard work.”

The view either side of the road was of featureless reddish-brown sand and rock, a portion of the Arabian desert that covered most of the Middle East regardless of border lines on a map. This made all three of The Doctor’s companions sceptical about that description of something rather inviting to look forward to.

But their worries were unfounded. The shining river and a copse of fig trees came into view after a half an hour more of jolting along increasingly narrow and more rutted roads. Soon a white walled, flat roofed house surrounded by a tent village came into view. As the truck stopped in front of the house a woman in sand-coloured breeches and a blue blouse came out to wave at the new arrivals. She looked about forty, with fine features and an authoritative set to her expression.

“Doctor!” she cried happily as they spilled out of the truck, bringing with them the postal items and the flour, leaving Jean-Claude to carry the liquor into the house. The Doctor cried back delightedly.

“Max!”

Her friends did some mental adjusting. They had assumed that Max Devine was a man. After all, it was the nineteen-thirties. Men tended to be the ones in charge of interesting stuff like this.

But, OK, Max, short for Maxine, was a woman in a man’s world. That was the sort of person The Doctor WOULD be friends with.

What still puzzled them was how they had become acquainted.

“Well, what do you think I do for the weekend when you lot all go home for a bit of ‘normality’?” The Doctor answered when Yasmin asked. The two of them had been showed a clean but basically furnished room with two beds, cupboards and a stand where a jug of hot water had been delivered for them to wash before dinner. Graham and Ryan had a similar room next door.

“So… we’re in Sheffield for three days and you’re in Iraq for months getting to know a whole load more people.”

It obviously made perfect sense to The Doctor. The more she thought about it, Yasmin realised that it made sense to her, too. She just hadn’t considered the idea before.

Anyway, here they were, with the sun setting behind the fig trees outside the window and somebody banging a gong and calling them to dinner.

The long table in the dining room quickly filled with the men and women who made up the expedition staff. Max quickly introduced The Doctor’s friends to the established group. First there were the two archaeologists attached to the University of Liverpool, Paul Newton and Gregory Anderson, both rugged, tanned men in their late thirties. Professor Anderson had his wife with him. Mrs Deborah Anderson was the only person who didn’t look as if she belonged in a house full of archaeologists in a desert. Unlike Max with her face tanned from daily work in the sunshine, Deborah had the peaches and cream complexion of an English woman and manicured hands that obviously didn’t do much housekeeping. It was hard to see what her role was in a place where everybody else was pulling together in one cause.

Harry Bailey, mid-twenties, sandy haired and smiling at everyone, was the official photographer, keeping the visual record of the dig.

Of course, they had already met Jean-Claude, but they had not yet talked to him properly because the truck engine was so noisy any conversation had been impossible. He was sitting beside Yasmin at the table and exchanged small talk with her as he passed butter or salt as required. Yasmin thought she might get to talk to him in more depth as they got to know each other better, and she found she wanted to do so.

“Now we have you all to complete our ‘Happy band’,” Harry said, still smiling. “We’ve been in need of an epigraphist. The chap we had last season at Nineveh has joined the Mallowan dig at Ur.”

It was a second or two before Ryan realised that Harry was looking at him.

Ryan was the new epigraphist.

Which would be fine if he knew what an epigraphist was.

“We’re certainly going to need you soon,” Max told him with a warm and encouraging smile. “The Akkadians wrote EVERYTHING on clay tablets and we’re bound to find plenty of them. You’ll be busy translating all day. As for you, Yasmin, the unwritten record through the pottery fragments will give you plenty of work in your own line of research.”

Yasmin began a vague response but was cut off, rudely, she thought, by Professor Newton.

“Isn’t Epigraphy an unusual career for somebody like you?” he asked Ryan. “Where did you study?”

“University of Sheffield,” Ryan answered, knowing from an inscription on the front of the original red brick building in the city centre that it actually went back to the 1900s.

“Really?” Newton remarked with raised eyebrows. “I didn’t know that establishment was noted for its ancient language researches.”

“Well, now you do,” Ryan answered. He had strong suspicions that ‘somebody like you’ referred to his colour, not his northern working class roots, and he didn’t like the implications. It hadn’t escaped his notice that everyone around the table except himself and Yasmin was white. They were served by native girls in maid uniforms. The food was probably cooked by natives, and he was aware that the tents outside were occupied by native workers who were eating around a camp fire.

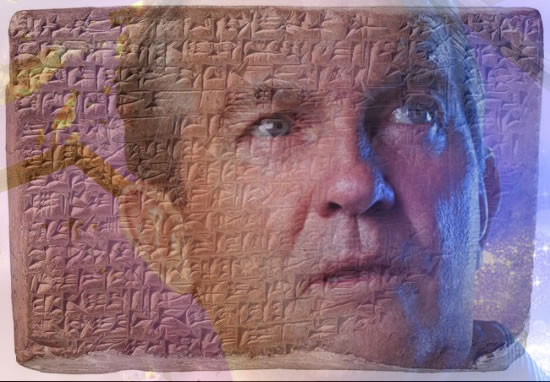

“Can you read the inscriptions on that picture up there?” Harry asked, pointing to a framed enlargement of a photograph on the otherwise bare wall. Ryan stood and went to look at it. He noticed that Akkadian, if that was what he was looking at, was one of those languages made up of very simplified pictures, drawn on wet clay with a stick or stylus.

Then, because he had travelled in the TARDIS and languages, written and spoken, were a gift of Time Lord technology, he read the words.

“It’s… written by a child, a girl, writing about her dolls,” he said. “It’s a little girl’s school essay.”

Everyone except Professor Newton smiled and clapped softly.

“That was one of my first efforts at archaeological photography,” Harry said with an even wider grin of proud enthusiasm. “Two seasons ago at Nineveh. I loved that it was such an ordinary, normal thing just like a modern child might write with pen and paper, but it was as much as ten thousand years old. It was what made the past real to me.”

Everyone else around the table, except for Mrs Anderson, agreed that it was things like that, connecting the past with the present, that made them love their jobs. The Doctor smiled enigmatically and thought that her reasons for exploring time and space were not dissimilar.

“Sit back down and eat,” Max told Ryan. “And don’t worry. That wasn’t any sort of test. The Doctor told me already about all of you and the skills you can bring to our expedition. We know Professor O’Brien is a distinguished paleo-anthropologist, but we didn’t dig up a skeleton for him to examine over dinner.”

Since Graham was the only one who DIDN’T know that he was a distinguished paleo anything he was glad when Mrs Anderson sighed rather theatrically and asked if they might talk about something other than archaeology now. They worked on dingy bits of broken pots all day. Could there not be something else to discuss at dinner?

Unfortunately, that led to a political discussion, one in which Professor Newton was fulsome in praise of the new regime in Germany and his colleague Professor Anderson was vehemently opposed. Mrs Anderson tried to talk to the other women at the table about fashion, and was not entirely successful since neither Max nor The Doctor were especially interested in fashion and Yasmin’s ideas of fashion were ninety years too late.

Ryan and Graham talked about photography with Harry – an easy topic since Harry happily talked about the subject without noticing he was the only one doing any of the talking.

Yasmin continued the small talk with Jean-Claude which she found a pleasant enough distraction from Professor Newton’s disturbing fascist obsession. She thought his accent charming and was a tiny bit surprised when he told her she spoke French beautifully. She hadn’t even realised that they had both been speaking French. The TARDIS gift again!

She was quite pleased after dinner when Jean-Claude invited her to walk outside with him. Ryan and Graham had been invited to Harry’s dark room to continue their talk. The Doctor and Max had catching up to do, still. Nobody really noticed them slip out past the tents where the native workers were lounging about at their leisure, talking in Arabic about nothing in particular.

“We shall stay away from archaeology, still,” Jean-Claude said after pointing out the ‘Tel’ or ‘hill’ that was being excavated. He brought her, instead, through a stand of trees to the river. There was a moon up and the air was still warm. There was the pleasant sound of night birds in the trees.

“I hope you will enjoy being here,” Jean-Claude said to her. She noticed that he said ‘you’, using the French singular pronoun not the plural to mean ‘you and your friends’. The difference was important.

“I think I will,” she answered. “Most people have been nice, so far. Well, except….’

“Professor Newton?” Jean-Claude sighed. “This interest in fascism is new. It is something he has picked up since last season… or perhaps he has only now felt emboldened to show his sympathies. I find his views unpleasant hearing. I have many Jewish friends at home.”

“Not just him. When we were going along to the dining room, Mrs Anderson was complaining about getting too much sun on her arms and face. She looked at me and said ‘some people don’t have to worry about their complexions’. Apart from being racist, it isn’t even true. Brown skin can burn, too.”

“Mrs Anderson isn’t really a racist,” Jean-Claude assured her. “That requires thought even if it is wrong thought. She is just empty-headed. Her mind fills with whatever she hears without any consideration of what then comes out of her mouth.”

Yasmin thought that might be a fair description of Mrs Anderson, but even so, the next air-head comment of that sort from her would be challenged.

She steered the conversation to Jean-Claude, asking him about his life before he became part of an archaeological expedition. He talked about growing up in a village near Lyon, of not entirely successful university studies and being uncertain about what he wanted from life. He had come to the Middle East partly as a holiday and partly to see if he could make himself useful in some way. He had joined Max’s Nineveh dig two years ago and although he was far from an expert in antiquities he had enjoyed the work and the camaraderie. He drove the truck, collected mail and groceries, made sure all the necessary supplies were obtained for Harry’s photography or Max’s very detailed drawings of the sites, even the rolls of felt for wrapping delicate finds and the tubs of plasticine used to make impressions of the tablets they hoped to find. And as long as those things needed organising he was happy to be of service.

“One day, perhaps, I will go home and be a clerk in a Lyonnaise solicitors office and be bored out of my head, but for now I am happy.”

“Perhaps something will come up so you don’t have to be bored,” Yasmin told him, thinking that she was so lucky to have her own life raised above the commonplace by meeting The Doctor.

Jean-Claude smiled and agreed that anything was possible.

Then Yasmin remembered that there would be a war in four years’ time. France would be invaded. She really didn’t want to talk about what might happen in Jean-Claude’s future any more than she wanted to think about this country’s far future.

She had inadvertently stepped away from Jean-Claude. He moved closer and reached for her hand. It wasn’t any kind of ‘come on’. She recognised that and let him take it gently. But he had sensed a change in her tone of voice and perhaps her body language and wondered why.

“I’m sorry,” she managed to say. “It has been a long day, travelling, you know. The tiredness just hit me. I think I’d better go back to the house. I should get an early night… lots to do tomorrow.”

All that was true, of course, and she thought Jean-Claude understood. He walked back to the expedition house talking about tomorrow’s work on the dig. He didn’t notice that Yasmin wasn’t talking bac - or was kind enough to pretend he didn’t notice.

The Doctor also studiously didn’t ‘notice’ that Yasmin was quiet when they settled to sleep. She was grateful for the forbearance.

The next morning, after a hearty breakfast, there was plenty of interesting work to do. Under a canvas canopy, Yasmin was aided by two native boys in cleaning and sorting pottery that was being brought out of the exploratory trenches. Many of them were broken into dozens of pieces, some were incomplete. Just occasionally there was something nearly intact. And despite knowing nothing about Akkadian pottery, Yasmin found herself drawn into the work of cataloguing the finds and putting them carefully into crates to be taken back to the house where she would get to reassemble some of them with copious amounts of glue.

Ryan had his own pair of native boys washing clay tablets before he packed them in crates, carefully separated by layers of fig tree leaves, the nineteen-thirties equivalent of bubble wrap.

He wasn’t sure how he felt about the native boys, most of them too young even to legally do a paper round in modern Sheffield, working for him that way. He talked to them and found that their fathers were working on the dig, too. They were the men in long shirts and cloth headdresses who got on with spades digging down into the Tell before the archaeologists took over with the careful, systematic work involving trowels and handbrushes. He asked about school, but the boys just laughed. There were no schools in their village.

It didn’t seem right. But there was nothing he could do except speak to them decently and ask, rather than demand, their services.

When it got too hot for outdoor work in the blistering afternoon, Yasmin and Ryan had joint share of a cool, shaded workroom where they unpacked the morning’s finds and got to work with tools they thought they had left behind at primary school. Yasmin worked on her three-dimensional pottery jigsaws with a glue pot while Ryan rolled out slabs of grey plasticine and used it to make ‘negative’ imprints of his clay tablets. From these, much like Harry in his dark room making prints of the dozens of photographs he had taken, Ryan made plaster of Paris copies from the plasticine moulds while his boys repacked the originals in more fig leaves for safety. Translating the copies was less nerve-wracking for a man with dyspraxia.

Day after day fell into a pattern like that. The day’s work was followed by relaxing and sociable evenings. Yasmin avoided conversations with the empty-headed Mrs Anderson who only cared about clothes and make up and getting back to her social life at the end of the dig. Yasmin knew enough people like her at home and didn’t talk to them, either.

Ryan avoided Professor Newton in any situation. He didn’t like him at all. In the evenings he and Graham gravitated towards Harry and the fruits of his darkroom. The young man’s infectious enthusiasm made him easy to like.

The Doctor and Max spent their evenings poring over the partially drawn map of the unnamed and long lost Akkadian city, trying to fill in the blank sections.

Trying, above all, to find the ancient Akkadian cemetery. Until they did, Graham’s job as ‘paleo-anthropologist’ was unfulfilled. Graham wasn’t too worried about that, since he still wasn’t sure what he was meant to do and was happy enough joining in with the less sensational work with the trowels and brushes. He was rather proud of a small earthenware jar, still sealed with wax and still containing an ointment something like the biblical myrrh, that he had dug up all by himself. He could happily carry on finding that sort of thing and leave skeletons alone.

For Yasmin, the warm evenings under fig tree copses with the sound of the Tigris waters slipping by and night birds whose sounds were becoming comfortably familiar were centred on her strictly non-romantic association with Jean-Claude. She avoided thinking about the future in any form and the past in any context except the strictly archaeological and concentrated for a few hours each evening on a very pleasant and untroubled ‘now’.

She knew that such a status quo wasn’t likely to last, but at least it lasted three very peaceful weeks.

The beginning of the end of Yasmin’s tranquillity came with a discovery at the dig that Max and The Doctor had been hoping for and Graham secretly NOT hoping for.

It was a grave site.

Not a whole cemetery as expected. They were still puzzled about where that was.

But a grave that was possibly worth all those ordinary burials put together.

It had been Graham, along with two industrious native workers, who had found it in the far end of the long trench. Even without any qualifications in paleo-anthropology he had recognised the shape and texture of a skull before other parts of a skeleton he could name less easily.

He also saw a telltale glint of buried treasure.

“Boss!” he called out. The Doctor and Max both answered to that title around the dig, and both came at a run. Both exclaimed in excitement and got down on hands and knees to join in the work of uncovering the body.

“It has to be royalty,” Max commented as more bones and more glittering precious metals were carefully uncovered, each stage diligently photographed by Harry for the official record.

“She must be,” Graham agreed. His identification of the skeleton as a ‘she’ was based on modern concepts of jewellery wearing rather than any understanding of male and female pelvises and other such anatomical clues, but as it happened, he was correct.

“She’s a tall girl,” The Doctor remarked.

“She seems to be,” Max agreed. “We’ll be able to make accurate measurements later.”

Graham was surprised that the lady’s height was such a concern to The Doctor and Max. For him, the fact that she was ‘blinged up’ from head to foot with headdress, earrings, multiple neck decorations, bracelets, armlets, anklets, belts or girdles of gold and precious and semi-precious stones, was what struck him the most forcefully.

Then it occurred to him that they were very deliberately playing down the find. The diggers and the boys were honest, but they had friends and families in villages within walking distance. Talk – especially talk about treasure - easily spread.

“Go carefully,” Max said. “Don’t try to rush anything. But there is no question of leaving her in the ground overnight. We must get her into the antika room before sundown.”

That was such a priority that all of the senior archaeologists took a hand in the work of freeing the skeleton from the three thousand year old soil around her.

Which was why Ryan was on hand when the clay tablets were discovered.

There were twelve of them, stacked underneath her head, almost like a pillow. They were in what Ryan had come to recognise as very excellent condition. Despite not being a real, qualified epigraphist, he was excited.

“We’ll find out who she was from them,” he said as he helped pack them in fig leaf layers. “This will be really something.”

Graham smiled as he watched his step grandson at work. As he had often noticed, when he was absorbed in something important, Ryan forgot all about his dyspraxia, which meant he didn’t drop any of the precious tablets or step on anything else of importance.

It took most of the day to get the bones of the lady onto a stretcher which was borne by two of the most trusted of the native workers. Max was at their side as they made their way to the expedition house. Graham walked with The Doctor a few feet behind.

“A stretcher…” Graham chuckled. “I’m afraid it’s a little late for paramedics.”

The Doctor smiled at his joke. She knew it was his way of getting over his feeling, inherited from a long line of church-going Englishmen, that exhuming a body was a little bit indecent. Since that was exactly what paleo-anthropologists did, it was a feeling he needed to keep to himself.

“She must be some kind of royalty,” he added in more serious tones.

“Yes,” The Doctor agreed. “But WHO’s royalty, I’m not sure. There’s something… in the back of my mind… something I can’t quite pin down….”

“It’s not the sort of bling she’s wearing?” Graham asked. “The blue pieces… I recognise that from programmes on Yesterday. Lapis Lazuli… it comes from Afghanistan, nowhere else. Always Afghanistan… which is a long way from here.”

The Doctor nodded.

“The brilliant red jewels are carnelians. The closest place they come from is Russia. But that’s not it. Akkadian trade links with far flung places are perfectly understood. Professor Anderson has studied that sort of thing for a long time. Ask him… or ask his wife. She is all too accustomed to taking second place to bronze age people.”

“Ah… that’s why she always has a long face,” Graham noted. “But she married an archaeologist, what did she expect? It’s like one time Grace thought I was looking at… something I shouldn’t be looking at… online. When she found it was a website about Routemasters through the years she laughed and said she could live with me having one of those as my mistress.”

“She was a one in a million,” The Doctor agreed. “But Mrs Anderson is….”

They were close to the house and a lot of angry shouting was coming from the workroom. The Doctor and Max exchanged anxious glances.

“You get the body to the Antika room,” The Doctor said. “Graham and I will handle this.”

The party split that way. Graham hurried after The Doctor and the two arrived at the workroom to see a near frozen tableau of figures.

Least important of them, but noticed first by The Doctor, was one of the native boys who was crying to himself under the table. Professor Newton and Ryan were facing each other at a distance once described as two sword lengths. Newton was holding his nose which was bleeding.

Between them was Yasmin, exercising her most fundamental police officer skills.

“What happened here?” The Doctor asked Yasmin, ignoring both men for the moment.

“I was here sorting pottery fragments. Suffi, Mr Sinclair’s errand boy, came in with a packing box which he placed on the table.” She indicated the box Ryan had sent down from the dig site. “Professor Newton came in and accused Suffi of dropping the box outside. When Suffi denied doing so, Professor Newton assaulted him – assaulted Suffi - with a stick – several times. When I protested he swore offensively and used derogatory language. Ryan… that is… Mr Sinclair… came in at that moment. He grabbed the stick and threw it over by the sink.”

Everyone looked around to see a thick piece of wood that could certainly break the limbs of a defenceless boy. Feelings of contempt for Professor Newton were spreading as Yasmin continued her verbal report.

“Professor Newton again swore and used derogatory language, this time towards Mr Sinclair, and then raised his right arm to punch Mr Sinclair in the face. Mr Sinclair dodged the blow, then was heard to say ‘I kept quiet in bloody Montgomery, bloody Alabama, but I’m not taking that right here, right now, from an outright bully like you.’ He then punched Professor Newton in the face. Before any further altercation could occur you and Mr O’Brien arrived.”

“Very clearly expressed,” The Doctor told her in the even tones of a superior police officer. “Does anyone have anything to add?”

“I want him dismissed,” Professor Newton replied, pointing at Ryan with a slightly shaking but accusatory finger. “I want him prosecuted tor common assault. I’m not going to stand for that from a common….”

The three citizens of Sheffield all registered their disgust at a word they had not heard even in some of the most disreputable of that city’s late night streets. The Doctor glared at Newton with the full force of her alien but aristocratic ancestry and succeeded in making him blush slightly.

“You’re dismissed,” said Max, coming into the workroom at that moment.

“I am glad you’ve seen sense,” Professor Newton said to her. “Treating these people as equals is always a mistake. I….”

“No,” Max interrupted. “YOU are dismissed, Professor Newton.” She nodded to Yasmin who bent to Suffi, still crying under the table as well as listening intently to what was happening. She took him to the sink and set to washing away his tears with a cloth and ensuring that he was not injured. “This is THEIR country,” Max continued, looking not at anyone else in the room, but at Suffi. “WE are their guests. If you cannot treat them with respect you have no place here. Pack your belongings. Jean-Claude will drive you to a hotel in Mosul. Be grateful his father is not pressing charges for assault and battery.”

Professor Newton was astonished. He expressed his astonishment with several disconnected words, but Max had turned away, back to the important work of securing a three thousand year old skeleton and her jewels. Professor Newton walked past five people, including Suffi, who stood between Yasmin and Ryan and watched him go.

“Well….” The Doctor said. Yasmin and Ryan looked at her, expecting something more, but she just smiled at him and went after Max.

“I didn’t drop the box,” Suffi insisted when the room was quiet.

“I’m sure you didn’t,” Ryan assured him. But when he opened the crate he was astonished. Yasmin looked over his shoulder and gasped in horror.

There wasn’t a single tablet that wasn’t broken into at least a dozen pieces. By the sound when Yasmin rocked the crate slightly, some of the bottom tablets might have been reduced to dust.

“It wasn’t me,” Suffi insisted again.

“We believe you, sunshine,” Ryan assured him. “I don’t know what happened.”

“Maybe Newton did it just to make trouble,” Yasmin suggested. “Look… it’s not a complete disaster. I’ve put together worse messes than these… real three-d jigsaws. Look at that vase over there. And that huge blue plate. Let’s get cracking… or some other word for it. Suffi, you know how to mix up the glue. Let’s get the first one laid out on the table and see where the joins are.”

Ryan had never done a jigsaw in his life. He had never worked out how to make more than two pieces lock together at once. This was not the puzzle he would have chosen to have a go at when it really mattered.

But Yasmin was there to help, as well as Suffi, standing by with the glue pot. The work was slow and he worried constantly that something might go wrong – two tablets might be stuck together, or an important set of texts put in upside down.

But before the sun went down they managed to salvage the first four tablets.

“I’m not going to attempt to do the thing with the plasticine until morning,” Ryan admitted as he looked at the fruit of their labour. “Let’s go to dinner. Suffi, good lad, you go and tell your dad we’re well pleased with you and you should have second helpings of whatever you’re all having.”

Suffi smiled widely and ran off to where his father and the other workers were already gathering around their campfire. Jean-Claude was arriving back from his distasteful errand to Mosul as Yasmin and Ryan made a quick ‘toilette’ to wash away the stickiness and the smell of the glue and headed to dinner.

The subject of Professor Newton was avoided at dinner. The subject of the Akkadian Royal Lady, as they had come to call her, was thoroughly chewed over, with Ryan and Yasmin getting to talk at length about their efforts to repair the tablets and identify the Lady.

It was a triumph for Ryan, especially. He enjoyed the fact that such well qualified people as Max Devine and Professor Anderson were listening to him with genuine interest, as if he were an intellectual equal to them.

He had said all he could say on the subject when Mrs Anderson, for the first time ever, took an interest in archaeology.

“Is it really true that she is completely covered in gold and jewels?” she asked.

“Not completely covered,” her husband answered. “I must say that my first impressions are mixed. The designs are not typically Akkadian. There seems some suggestion of mixed culture. Not Sumerian or Babylonian, or anything I might have expected….”

“But it is all gold,” Mrs Anderson cut in before he had been able to make what was almost certainly an important point. “Could I try some of it on? I could be like Frau Schliemann. Harry could photograph me in all the finery.”

“He will do nothing of the sort,” Professor Anderson responded. “This is a respectable, British expedition. We do not play dress up with important artefacts.”

Max nodded her agreement. Everyone did, even Yasmin and Ryan who had never heard of the German discoverer of ancient Minoan treasures who, some fifty years before had allowed his wife to be photographed wearing ‘Priam’s Treasure’. They didn’t know that Schliemann had been criticised for allowing important work to be trivialised and sensationalised. But even without such knowledge they saw the empty-headed folly in Mrs Anderson’s words.

Her nonsense spoiled the discussion of the Lady, but the meal was almost over and everyone went their separate ways.

Yasmin went for a walk with Jean-Claude as she had done every night since she arrived at Tel Kayifa.

It was around about then that something started to feel wrong. Though the night was as warm and fragrant as ever, Yasmin felt an unidentifiable uneasiness that spoilt the walk tor her.

Jean-Claude sensed something, too, and tried to explain it away.

“Don’t worry about Newton. He hates the French, too,” he said. “He called me some names when I left him in Mosul.”

“Oh, I’m not bothered about Newton,” she assured him. “I’ve seen worse than him. I don’t know what it is. Something… is wrong. But the only thing I can think of is the tablets. Suffi DIDN’T drop them. It was as if something malevolent was involved. Something not quite natural. But… that’s not the way clever people like us are supposed to talk. We don’t believe in ghosts, poltergeists, jinns, whatever. So it makes no sense to think that way let alone say it.”

“As England’s great playwright said, ‘There are more things in heaven and earth….’ Perhaps there is something we modern, educated people easily dismiss. Or perhaps there is a purely human devilment at work. Some jealousy or pettiness of that sort.”

“You could be right,” Yasmin agreed with a resigned sigh. “We’d better get in now. I should get an early night and be ready to help Ryan tomorrow.”

But tomorrow brought new reasons to feel uneasy.

|

|

|