The four oldest Chrysalids were talking excitedly among themselves both out loud and telepathically as the interplanetary shuttle came in sight of Beta Delta III. They were all talking and thinking about what lay ahead of them on the planet they were landing on in a few hours.

All last week they had sat the public examinations that proved their academic ability. Now, with their results in hand, they were going for interviews to see if they were the right material for the prestigious University of Nova Castria, the best in the Beta Delta system. Even the Chrysalids couldn’t be sure that they would be accepted. Nova Castria didn’t just ask for academic excellence, but much more, besides. They knew they had just a half hour each with the selection committee to prove they had the character to be Nova Castrians.

They all wanted to be. Nova Castria was the university with the best reputation. It was the one the Space Programme, the Diplomatic Corps, the Government ministries, and all of the top industries looked to for their graduate programmes. And it had the best post-graduate research facilities. Marle and Laurence both had their hearts set on a future in academia. Pieter was hoping for a career in politics. Angela wanted to design space craft for the Aeronautics Division. They all wanted to be the best. And they had to prove they were the best by the end of this afternoon.

Chrístõ listened idly to the general buzz of their conversations and just felt very old. It seemed so long since he had been to a similar interview at the Prydonian Academy. It WAS a long time. He had been twenty years old. He took his final exams at the age of one hundred and eighty. He had been a student since before Nova Castria University was founded.

Even so, he remembered it all so well. He remembered that interview, the cold faces of the four Lords of Faculty as they looked at him. He felt small and insignificant. They spoke with cold, hard voices. They tried all kinds of mind games to remind him that, as a half blood, he would have only a slim chance of success. He remembered Lord Artexian asking him why they should waste the resources of education on his watered blood. There were four Caretakers with excellent Academic results, full blooded Gallifreyans, who deserved the place more than he did. All he had was his father’s name to commend him.

His father’s name. That was why he had fought to get into the Prydonian Academy. The school his father, grandfather and countless male ancestors had all excelled in. That was why he had wanted to be a Prydonian. Not that he expected much more sympathy for his half blood from any other of the Academies. If anything, Prydonia was more amenable to him than the others. But he knew he would be a Prydonian or nothing.

He won his place. And not at the expense of any Caretaker with equally good qualifications. He was sure of that. He arrived on the first day, proud to wear the uniform of a Tyro, the scarlet tunic over the loose trousers in pale gold. One day, he knew, he would wear the deep gold and scarlet of a Senior. One day he would be a Prydonian Graduate and, more importantly, a Time Lord.

He had no illusions even on that first day about whether he was going to be happy there. He had been fairly sure he wouldn’t be. Even among his fellow Tyros there were whisperings about him. Those self assured Seniors sneered and turned their heads away. The Masters looked at him as if he was some kind of worm.

“Was it really like that for you, sir?” He heard Angela’s voice in his head. He hadn’t realised that his thoughts had been so open to them. He ought to practice some of those blocking techniques he had taught to them.

“You don’t have to call me sir,” he told her. “I’m only officially your teacher for another three weeks.”

“Chrístõ,” she said with a slight blush and a smile. “But truly, did you really feel so small and alone on your first day at college?”

“I felt small and alone on so many days,” he answered. “But you don’t want to know about my school life.”

“Yes, we do,” Marle said. “Yes, please, we would like to know. Your life is so very different from ours. Really… you were twenty years old when you first went to school?”

“Yes,” he answered. “That’s how it works on my world. I was privately educated for the first two decades of my life. I loved learning. I wanted to learn everything I could, about everything. Astronomy, temporal physics, biology, chemistry, thermodynamics, history, poetry, comparative religions of the galaxy, philosophy, anthropology, I drank in the lot. And I really wanted to get to the Academy. Because there I would have so many new things to learn. So many opportunities. The great library, the planetarium. The science labs, and when I was older, the chance to learn to pilot a TARDIS. I wanted all that. I just… didn’t want to be hurt every day in order to do it all.”

“You were hurt?” He felt a gentle empathy from the two girls, but the boys were listening, too, and they, also, understood about school bullies. They had all been taunted for being the brainy ones in their classes, and Pieter, before puberty shot him up to six foot and the climbing he did as a hobby gave him a better physique, had been picked on by boys whose bodies had developed faster than his own. He tried not to think it, but he did. They were all rather shocked to learn that their sufferings were tiny compared to his own experiences. But they still asked him to tell them.

His cousin had been allocated the same dormitory as him. Of the eight Tyros in the room, their beds separated by thin partition panels, he was the only one he knew. Rõgæn was the only other one from the Southern Continent. The others all lived on the Northern Continent, mostly in the Capitol itself. Rõgæn had been teased already for his southern accent as they were unpacking their personal belongings and putting them in the bedside cupboards and drawers. Chrístõ hadn’t been, simply because he hadn’t spoken to anyone yet and they hadn’t had cause to criticise his rolling r’s and his long vowels.

The Chrysalids were puzzled by that. Different accents were a part of life as colonists. Almost all of them spoke with a hint of their Earth ethnic origins. They all accepted that as part of their diversity along with hair and eye and skin colour, and nobody would think of picking on anyone else about it. Angela sounded like a Californian, after all. Marle and Laurence were what Chrístõ would call Home Counties England. Pieter’s Swiss/Austrian cadence was pleasant to listen to, and Chrístõ often chose him to read aloud in the English classes for that reason.

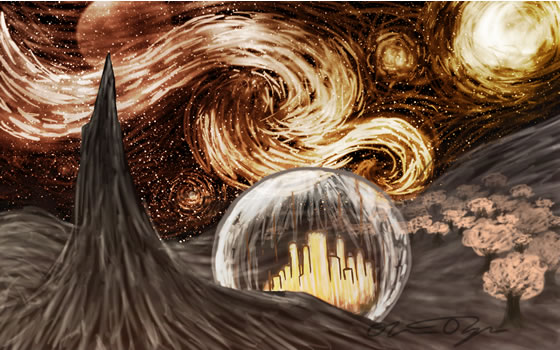

“It was a stupid kind of snobbery,” Chrístõ said. “Rõgæn and I came from huge country estates, a far superior lifestyle than city living with an artificial climate under a protective dome. They got at us because we were the minority. That’s the way it is, just about anywhere I’ve ever been.”

It might not have been so bad if they had stuck together. But as the laughter died from another joke about Rõgæn’s accent, he heard his cousin say something that ensured his own acceptance and Chrístõ’s isolation.

“I may be from the south,” he said. “But at least I’m a pure blood. Not like that mongrel, Lœngbærrow.”

Chrístõ’s hearts had sunk as he heard that. It was mean and shabby of Rõgæn. He knew, of course, that he would be picked on for that sooner or later, but it burned him that the one person who might have stood by him, with whom he had a loose blood connection, had instigated it.

Rõgæn took no further part in the petty comments about half bloods that followed. That was the curious thing about it. After setting him up, he just continued unpacking in his bedspace opposite.

“Why did you do that?” Chrístõ asked his cousin as they went to their induction lecture. “You didn’t have to tell them that.”

“Tell them what?” Rõgæn answered. “That your mother was a weak-blooded foreigner who dirtied the bloodline of your House?”

“If my father heard you say words like that…” Chrístõ began. But Rõgæn laughed nastily.

“Your father can’t hear me,” he answered. “We’re a long way from home, both of us. You can’t run to your precious father. And you can’t go telling him at the weekend, either, because a sneak is even lower than a mongrel or a Caretaker.”

“And that’s your cousin who said that?” Pieter asked with a disgusted tone in his voice.

“My cousin.” Chrístõ shook his head and smiled wryly. “Technically, actually, he is much further removed than that. But I was taught to call him that for the sake of simplicity.”

The induction had not been so bad. All he had to do was sit and listen as the Master of Tyros went through what was expected of them all. He took note of the rules, of what he was not allowed to do. He looked at his time table of classes. When he saw the subjects he was going to be learning from tomorrow morning he felt excited. He couldn’t wait to get started.

If lessons were the only part of it he would have been fine.

After that it was lunch. He walked along with the other Tyros into the huge refectory where they would have all their meals except supper which would be served in the common room on the ground floor of the dormitory house. It was a huge, beautiful room, lit by great chandeliers hanging from the white ceiling adorned with relief carvings of heroic Gallifreyans of more exotic days. The walls, too, had friezes and reliefs on them and it looked simply magnificent.

But the room terrified Chrístõ. The noise of thousands of voices all talking at once, the clatter of cutlery and china, the whole cacophony was too much. He had never seen so many people in one place before, and he felt lost amongst them all.

He looked at the table where he was expected to sit, four Tyros and a mixture of older students with one of the Masters at the head of the table. He couldn’t bring himself to take his seat. He saw a basket of fruit and nuts placed in the centre. He grabbed a moon fruit and a handful of cúl nuts, shoved them in the pocket of his tunic and turned away. He fought his way through the mass of people trying to come in and found himself, at last, in the space and cool air of the quadrangle. He sat by the fountain in the middle and ate the fruit and nuts. Cúl nuts were highly nutritious and he liked the taste. They would sustain him for the afternoon session in which they were actually shown around the Academy and were able to familiarise themselves with the different departments – so there was no excuse for getting lost the next day when classes began.

Again, that wasn’t too bad. All he had to do was follow the others. Nobody could do or say anything nasty to him while a Master might overhear. And he was as impressed by the Academy buildings as he ever expected to be. The planetarium was wonderful. The music department, the science labs, filled him with longing to start his formal education. The library blew his mind. It was a huge rotunda with a high, domed, glass roof through which natural light came in and was augmented with carefully placed crystal arrangements that stored the light and gave it back in diffused, glare free quantities. A huge mosaic floor was underneath the dome. Desks and chairs, comfortable leather chairs for more relaxed studies, and banks of computer terminals were occupied by students hard at their quiet studies. There was no talking, not even telepathically, within the rotunda. There were dampeners on the building to prevent psychic chatter. Chrístõ felt it like a sort of cotton wool cloud around his mind. But he liked the feeling. It was peaceful.

He loved the library. He looked up at the galleries, ten, fifteen, twenty of them, all around. Tens of thousands of books. He wondered how many he could read in his years here as a student. He wanted to read them all. And he wanted to start now.

He hung back as the Tyros were ushered back out of the library having been issued the passes that entitled them to withdraw books for study elsewhere. Chrístõ didn’t want to take a book out, yet. But he longed to climb the steps, to walk through the stacks and find something to learn. Nobody noticed that he was missing as they went on. He slipped between the almost silently humming server units that maintained the printed newspaper archive and the index for all the volumes in the library. He found one of the spiral staircases that led up through the galleries and climbed it quietly, hoping nobody would look up and realise that his scarlet tunic marked him as one who had no business being here, yet. He kept on going, all the way up to the top gallery. It was empty. He looked through the books and found one among the thousands that might occupy his mind for a while. It was an astronomy book about the stars and planets of the Kasterborus system. He looked at the flyleaf and smiled. It was written by the foremost astronomer of present day Gallifrey, Chrístõ de Lún de Lœngbærrow – his own grandfather. There probably wouldn’t be a lot that he didn’t know in it. He had spent plenty of evenings on the roof of the house with the old man, looking at the stars through his telescope. But he was prepared to find some nugget of knowledge he didn’t have already.

He looked for a place where he could read quietly. There were chairs and tables on this floor, but there was always the possibility that he would be told to leave. Then he spotted a small door at the back of the stacks. It led to a narrow staircase that went up, not down. He climbed it and came out into a small room. Indeed, almost too small to be a room. It was simply a space behind one of the ornamental spires that surrounded the dome. It had a slit of a window that let in light and air. He looked out of it and was delighted to see the whole of the Academy grounds below. He could see the refectory, the science block, the drama department with its ionic columns, and gardens and fountains between each elegant building. He felt a moment of joy, knowing that he belonged to this gracious complex of buildings. He WAS a Prydonian.

But he was glad, right now, to be a Prydonian who had found a place where he had peace and quiet. He put his cloak on the floor and sat on it, his back against the wall, his knees drawn up. He opened the book. He lost himself for several hours in the beautiful, full colour prints of the planets in their orbits around their respective stars. Demos, Gallifrey, Karn, Polarfrey, Kasterborus and The Fibster were the planets that orbited the sun that lit his hideaway. It never had an official name. It was THE sun, after all. In his grandfather’s book it was marked as Pazithi. The other five major stars of the Kasterborus constellation were known as Arina, Quintus, Orn, Ghun and Tao. This he knew as easily as he knew his own name. The planets that orbited those stars….

His brain absorbed the technical details, the geographic, the astronomical information. His mind was enchanted by the beauty of the planets, each unique and amazing. He longed even more for the time when he might have his own TARDIS and be able to explore them by himself.

He didn’t even dare, yet, to dream of the freedom to leave his home system and travel across the galaxy to the other planet that meant so much to him.

Earth.

He would look some time, but he very much doubted whether the library contained any books about Earth. He knew only a very little about it. He knew that it had as much as ten times as many people on it as Gallifrey though it was actually about the same size. He knew what it looked like. He remembered when he was a little boy, in his bedroom in the Ambassador’s residence of Ventura IV, the first planet he knew as a child. He remembered the mobile over his bed. Two planets, lit from inside, one blue and green, one red and brown, orbited each other as he drifted to sleep. He knew the red and brown one was Gallifrey, the world of his birth, home. The other was Earth, and his mother came from there. He slept soundly when he was that young, and dreamt of planets he had never seen.

When he went home, at the weekend, he decided he would ask his father to tell him more about Earth. He wondered why they had never visited there. He had travelled with his father to many places, but not there. He would ask him to memory visit with him, show him what it looked like properly. That was something to look forward to.

Meanwhile he reached into his tunic pocket and found something his father had given to him as a reward twelve years ago now, when he had gone through the first rite of passage of a Gallifreyan child, the Untempered Schism. Having looked time and space square in the face, he was given a watch. A silver fob watch. Time Lords never needed to look at watches, of course. They knew, in their very souls, what time it was. They felt each moment pass instinctively.

He felt several moments go by now as he looked at the watch case. This one was useless on Gallifrey. It was of Earth make. It only had twelve hours, not thirteen. It had a symbol engraved on the front that nobody else on Gallifrey knew unless they had ever visited Mount Lœng House, his country home. It was a bird, with wings outstretched and some kind of plant, perhaps an olive branch, in its long beak. It was the symbol, he was told, of the Earth city his mother came from. The same pattern was on the big rug in the front hall of Mount Lœng House, and in the drawing room and large dining room, picked out there in deep red and gold. He had first seen it when he came home to Gallifrey at the age of six, after his mother had died at the Ambassador’s residence. The rooms where he later began to have his private lessons also had the symbol on the carpet. These rooms had been his mother’s private suite, her drawing room, library and dining room, and they still had a lot of memories of her. The walls were adorned with pictures of that city she grew up in. It had a lot of big, tall buildings and a wide river running through it. Chrístõ longed to visit it. And London, New York, Paris. He wanted those places to be more than just names he had heard of.

He opened the watch. Of course, he didn’t use it to tell the time. But it was wound up and he listened to its tick and steadied his two hearts to match its rhythm. He looked at the miniature painting of a lady that was painted on the inside of the lid in bright enamel paints that had never faded. His mother, when she was young. She had grey eyes and soft brown hair and a soft mouth. She was dressed in a gown of russet red and she looked happy.

That was not really how he remembered her in the few memories he had of her. She was older when he was born. Still beautiful, but in a worn, frayed kind of way as if she might easily blow away on the wind. But in those fragmented memories, she was always happy. She must have been sad sometimes, but when he was near her she was happy. She smiled when she picked him up in her arms and introduced him to the joy of books as opposed to information wafers on a computer by reading to him while he nestled in her lap. She smiled at him. When he tired of being held he would play in the garden of the Ambassador’s residence and she would watch through the French door to the drawing room, or sitting under a shade among the roses. She watched him and smiled, and when she slept, as she so often did, she slept with a smile on her lips.

Or so he remembered, anyway. Perhaps it wasn’t always the case, but what he remembered was of her smiling and happy.

She was only in her early twenties in this picture. Many years before he was born. But she was his mother, and he loved to look at her in the watch.

“Mama,” he whispered. “I will try hard to do well. I want you to be proud of me, I want you and father both to be proud of me when I’m a Time Lord.”

He closed the watch and put it back in his pocket. He opened the book of astronomy again and lost himself for a few more hours in the accumulation of knowledge, dreaming of flying his own space capsule around the planets he read of, until his Time Lord awareness of time told him he could go down to the afternoon meal.

Tea was optional. It was a traditional meal that was out of favour with the more fashion conscious citizens of the Capitol, but for those who wanted it, food was provided. Chrístõ was hungry, having not eaten much for lunch. He filled a plate from the buffet counter and found a table in the corner where he might not be noticed. He ate his food and then went to his dormitory long enough to pick up his outdoor cloak rather than the lightweight silk one that went with the uniform and was merely ornamental. It was black, and covered the distinctive red and gold, allowing him to be a little more inconspicuous.

Students were allowed to leave the Academy for a few hours in the late afternoon, as long as they signed themselves out and were back in time for roll call. He walked the streets of the Capitol without thinking too much about where he was going, as long as he headed more or less away from the Academy. The Capitol was not his favourite part of Gallifrey, but it was interesting. It was not as crowded as a city might be. There was no ground traffic. Everything hovered up above at about the twentieth floor of the tall, graceful towers, parking on rooftop spaces. Only occasionally did a car descend to drop people off at ground level, usually chauffeured limousines that would return when called for. The streets were paved and fountains and sculpture adorned the plazas. It was the premier city of Gallifrey, and it was beautiful and elegant and imposing.

Right now, he would have preferred to be less imposed upon, but he was at least unmolested as he found himself at the bottom of the wide steps leading up to the entrance to the Citadel. It was the most imposing, the most elegant building in the Capitol, and yet the one he was most familiar with. It contained, among other things, the Panopticon, the chamber where the government sat.

The Council were in session this afternoon. He looked up once and then walked up the steps and inside. In the airy foyer he checked the list of debates and the Councillors present. None of the debates were of any special interest to a twenty year old boy, but it was a way of passing a couple of hours. He went up the stairs to the public gallery. He signed himself in and submitted himself to the electronic weapons check and was given a personal perception filter – a medallion on a length of ribbon that was imbued with some interesting properties. When he wore it, he became virtually invisible. He was unnoticed as he sat right at the front of the gallery, overlooking the Panopticon, and would continue to be so unless he did something really silly like shouting or jumping up and down to attract attention and break the ‘spell’ the filter projected.

His uncle Remonte was there. He wasn’t speaking right now, but he was listening to the Councillor who was, and he made notes on his electronic slate with his stylus. He would have plenty to say when it was his turn. Chrístõ had seen his uncle in debate before. His father, too. He was not a member of the council at present. He had taken up the post of Magister of the Southern Continent for a time, the job he held when he and his mother were first married. He had done that so that Chrístõ could be a weekly boarder at the Academy and be able to spend the weekends at home with him.

He didn’t really pay much attention to the debates. He let his mind wander. He imagined what it would be like when he was a Time Lord, and perhaps he, too, would be a Councillor. Maybe even a High Councillor, perhaps Chancellor. Four generations of his family had been Lord High President in their time. Was that an ambition too far for a boy who was still trying to get through his first day of school? He looked at the current President. He was a tall, stately, venerable man with wise eyes in his lined, aged face. He was nearly five thousand years old and on his last regeneration. He sat in the central, raised seat with the Chancellor and Premier Cardinal below him. The other High Councillors were arrayed either side, facing the ordinary Councillors, below the gallery Chrístõ was sitting in.

The debate ended just after his uncle spoke. Then the vote was called. The President’s yay or nay was taken first. Then the Chancellor and Premier Cardinal. If they were unanimous, then it was unlikely that any of the High Council would vote differently. The ordinary Councillors had a secret ballot, so it was sometimes known for them to go against the president’s decision, safe in the knowledge that fingers could not be pointed, but the High Council’s choices were always public knowledge.

Chrístõ often thought there was something not quite right about the way it was done. The opinion of the President and Senior High Councillors seemed to have too much weight. Chrístõ had read of a principle called primus inter pares – first among equals, by which even the leader of a government was not allowed to influence a decision any more than any other member. A word ‘democracy’ was used with it. And as he understood the word to be applied on other planets, Gallifrey’s system wasn’t entirely democratic. He was sure things could be done differently. Gallifrey could be a more equal society where there was no real distinction between Oldblood, Newblood and Caretaker, where every man and woman, regardless of class, had a full say in who was elected to the government.

He stopped himself. Those thoughts were almost treason. And he was sitting there in the Panopticon, thinking them. It was silly. Besides, Gallifrey was a good society. Even the Caretakers had no real problems. Everyone was as happy as they could be, more or less. Except the odd half blood who was still finding his feet.

But one day, perhaps, he would wear the regalia of a High Councillor and be one of those who ensured that the people remained happy and content.

The debates were over now. The President, followed by the Chancellor and Premier Cardinal left the Panopticon, followed by the other High Councillors. The chamber began to empty. Chrístõ filed out of the gallery along with the press and other members of the public. He signed himself out, but he put the perception filter in his pocket. He had an idea how he might use that. It wasn’t theft, exactly, he reasoned. Just a loan. He could drop it back another time.

He spotted his uncle in the foyer and ran to say hello to him.

“Chrístõ,” Remonte de Lœngbærrow said with a smile. “Are you playing truant already?”

“I’m signed out until roll call,” he answered.

“How is it?” Remonte asked him. “Are you all right?”

“It’s… I think I'm going to miss home a lot. And I don’t think I’m going to make many friends. But I am looking forward to the classes starting.”

“You’ll be all right, Chrístõ,” his uncle assured him. “Work hard and obey the Masters. Do your best. Would you like me to walk back to the gate with you?”

“Yes, sir,” he answered gratefully, and he enjoyed that walk back to the Academy, talking of familiar things. He said goodbye and signed himself in at the gate manned by an old Caretaker named Brynn.

“Evening, young sir,” said the old man. “You’ll need to hurry. Roll Call is in two minutes.”

“Yes,” he said and waved to his uncle before running across the quadrangle to the Tyro Hall. He was almost there when he accidentally bumped into a Senior who, being a Senior, wasn’t required to be at Roll Call. He lost his balance and fell, painfully. The Senior looked down at him as he sprawled stupidly on the ground and turned and walked away without a word. He was a Tyro and not worth the breath. But Chrístõ heard a sad crunching noise and when he looked he saw his fob watch on the ground. It had fallen from his pocket and the Senior had stood on it. He didn’t think it was deliberate. His watch was of as little consequence as he was. But it felt like a blow that he didn’t need. He picked it up and saw that the lid was broken off and the glass was cracked over the watch face. The portrait of his mother was intact, at least. He put the pieces into his pocket and ran to reach the Roll Call. He was there just in time not to have his tardiness remarked upon. He was glad of that. His survival through these first weeks depended on not standing out in any way, certainly not as somebody who was late or did things wrong.

After Roll Call was supper. He followed the others to the refectory, but again he found the room too full, too noisy. He took the bread rolls from his place and some cheese, as well as more fruit and cúl nuts and escaped again. He ate the food by the fountain in the now darkening quadrangle and then went up to the dormitory.

In future, of course, this time after supper would be study time. The common room would be susurrating with scribbling styluses and the bleeps of calculating machines. Tonight there was no prep to be done so it was quiet. He found one of his new text books in the cupboard by his bed and sat in the common room, with the perception filter around his neck. As he hoped, when the room filled up later with Tyros making the most of the last hours before bed none of them noticed him. Not even Rõgæn, who already seemed to have a group around him. None of them especially noticed his absence. And that was fine by him.

He waited until everyone else had been to the shower and was getting ready for bed before he did so. He got the bathroom to himself at least. When he was dried, he put on the regulation night attire, a long flannelette gown of deep red that covered him from neck to toe. It was actually more comfortable than the tunic and trousers he wore all day, but he wasn’t really used to wearing anything at night. He usually slept or meditated naked. That was the custom in the countryside of Southern Gallifrey, but obviously not something he was going to do in a room full of people who didn’t think much of southern customs, and even less of him.

He gathered his discarded uniform to put in the laundry basket – new clothes were issued daily to all students. He found the perception filter among the folds, but when he searched his pockets he couldn’t find his watch. He searched carefully, then frantically. He looked under the bench where he had left his clothes in the changing room. He looked all around the floor. But it wasn’t there.

He sat down on the bench, clutching the bundle of clothing and tried not to cry. He knew he didn’t want to do that where he might be seen. But it was his first day and he had lost the one thing that might have helped him get through the week.

Lost? Or was it stolen? But if it was, what could he do? Nobody particularly wanted to be his friend as it was. If he accused them of petty theft, where would that leave him?

The injustice of it stayed with him, though. Why would any of them take something so useless and worthless to them except as an act of meanness to him? Was he really hated so much already?

He dumped his clothes in the laundry and went into the dormitory. It was almost lights out. Everyone was getting into bed. He didn’t say anything to anyone. Nobody said anything to him. He got into his own bed and laid his head on the pillow. He waited for the lights to go out and the room to go quiet.

He smothered a scream as he felt his skin start to itch and then burn. There was something in the bed - a fine powder all over the sheets and the pillow. It irritated his flesh. It was even in his hair. He gritted his teeth. He didn’t dare say anything. He knew that one of the others must have done this to him, just as they had stolen his watch. He knew if he uttered a sound, he would be ridiculed.

He lay there for several hours, hurting, both physically and mentally, humiliated by the stupid, childish trick he had blundered into, hating those around him who attacked him so insidiously. He kept his breathing steady and blinked back the tears that would get him bullied even more. And he waited. He waited until he was sure everyone else was asleep. Then he stood up and walked out of the dormitory. He didn’t bother to go to the bathroom. He went through to the common room and looked in a mirror there. He saw his face, swollen and red, his arms covered in a burning rash. He knew a cold shower would soothe his skin, but if somebody woke and heard him in the shower, they would have their satisfaction.

He went from the common room to the stairwell across which was another common room, another bathroom and another dormitory exactly like the one he was in. They were on the top floor of the building. When it came to allocating sleeping space, it was in inverse proportion to seniority. The Tyros were at the top, out of sight and mind. The Seniors were on the first floor with their smoking room and stewards to attend to their demands for food or drink until they chose their own bedtime. That meant that the narrow staircase that carried on up must lead to….

Yes, he thought as he unfastened the door and stepped out onto the narrow, flat part around the sloping roof of the dormitory. There was a low, ornamental parapet and he looked down over it. It was a long way down if he fell. He would almost certainly die. But that didn’t worry him. He had a head for heights and he was in no way that miserable to want to jump, even though he felt quite low.

It started to rain. It was cool and refreshing, the controlled rainfall that came every night in the Capitol. It would go on for about three hours. Good enough, he thought. He pulled off his nightgown and cast it aside and stood there, naked, in the rain, feeling the cool drops of water on his burning skin. He was soon soaked through, but he didn’t feel the cold. He regulated his internal temperature while the rain soothed his pain.

If anyone could see him, he would have been a pathetic sight, his hair wet, his body dripping wet. At twenty he looked more like a skinny, underdeveloped fourteen year old of Earth Human measure. He was six foot tall, a man’s height, but his body seemed all legs, arm, and ribs. His arms were thin and his muscles pathetic. His legs hardly seemed capable of holding him up, sometimes. He was wretched. Of course he was not the only one. None of his fellow Tyros were much better, yet. It would take another ten years or so for any of them to begin to look like anything worth a second glance, and a century and half before they could claim to be the majestic sons of Rassilon who would inherit the universe.

Right now, he was pathetic, and he knew it. And he finally did what he had tried not to do all day. He cried, his tears mingling with the cool rain as he leaned against the tiles of the roof. He cried, feeling sorry for himself, knowing he was useless, weak, a friendless half blood with a funny accent, who nobody liked. He cried miserably until he ran out of tears.

He stopped crying, though he still felt miserable. He knew his body was starting to mend. At twenty, he couldn’t instantly repair wounds and hurts as he would later in life, but given the chance, his cooled, refreshed skin slowly began to mend. He stopped hurting physically, and that helped his mind to recover. He began to enjoy the rain, he enjoyed the loneliness of his rooftop place.

The rain stopped after three hours. By then, it was almost dawn. He crouched behind the parapet and waited. Sunrise over the Capitol, even with the protective dome between him and the sky, was spectacular. He liked sunrises almost as much as he liked sunsets, and this one was pleasant.

By the time the sun was high enough to cast its warming rays onto the roof of the dormitory, there was only another hour until the wake up bell. Chrístõ went down to the bathroom and took an early shower and was one of the first to be dressed in clean clothes. He crept back into the dormitory to pick up his perception filter. He intended to sit in the common room and read again until it was time for breakfast. He was surprised to see his watch lying on his bedside table. It was still in pieces, but no worse than before. He put it in his pocket and put the perception filter over his head and made the most of the calm before the storm. At least, later, he would be in classes, learning, as he wanted to be.

“Chrístõ?” He heard a soft, feminine voice and was surprised to feel the vibration and hear the hum of the shuttle engines. It was Angela who had called his name. He looked at her and realised his eyes were wet. He had been crying.

“Daft thing to do,” he said. “Good job I’m not going to be your teacher for much longer, cracking up like that.”

“Was it really like that? Your first day?”

“Yes, it was,” he said. “And it got worse before it got better. I think I spent every night for the first year on that parapet instead of in my bed.”

“They put stuff in your sheets every night?” Laurence asked.

“No,” he answered. “Turns out that wasn’t any of the Tyros. It was a stupid trick that the Seniors do every year. My bed was chosen randomly before I was even allocated it. The next night, they got my cousin, Rõgæn. He screamed the place down. Two of the others had to take him to the sanatorium.” Chrístõ tried not to smile. His students couldn’t help it.

“That’s called schadenfreude, and it’s not nice,” he said.

“Neither was your cousin,” Pieter said. “Was it he who took your watch?”

“Doubt it,” Chrístõ answered. “Rõgæn wouldn’t have given it back. Whoever did that had a guilty conscience. Rõgæn never even had a conscience, let alone a guilty one. Anyway, I took the watch home at the weekend. My father promised to get it fixed. But he told me it might be better if I didn’t take it to school. He said it would be better for me if I tried more to be Gallifreyan and didn’t think about Earth. That was why he had never taken me there. He wanted me to be a Time Lord, to be a Gallifreyan, to be proud of my heritage. He didn’t want me to forget my mother, or what she was, or to be any less proud of her, but he knew I needed to do all I could to fit into the Prydonian Academy, and it was enough of a struggle without setting myself apart from the others. So… I did as he said. I did my best to be a true Gallifreyan, and when I was called a half blood and a mongrel I turned the other cheek, I rolled with the punches. I tried to do my crying at night, in the rain, where nobody saw me.”

An illuminated sign came on in the cabin. It was time to put on seatbelts and prepare for the landing at the space port of Beta Delta III. The Chrysalids had lots of questions they still wanted to ask him about his Academy life, but now the butterflies returned as they contemplated their own futures.

Later, while his students were being interviewed by the panel of Nova Castria university, Chrístõ sat in a rather nice, airy, student café and drank latte coffee. He reached in his pocket and took out a silver fob watch he had owned for a long time. It wasn’t any use on this planet, either. Here there were only eleven hours in the day.

But he didn’t need it to tell the time. He was a Time Lord. He knew when time was passing. He let a few seconds pass now as he looked at the picture of his mother. He knew, now, a lot more about it. His mother had given his father the watch as a gift for their first wedding anniversary. When the portrait was painted she had good reason to smile a sweet, secret smile. She was pregnant. She was happy. Chrístõ knew that the happiness turned to tragedy not long after that. She lost the baby. It took a long time before she managed to give her husband the one gift he longed for – a son and heir.

He looked up from those musings as his students came into the café. They were all smiling as they came to the table with their certificates of acceptance.

“You see,” he told them as he hugged the girls and shook hands with the boys. “Nothing to worry about. And I promise you all, whatever happens, your first day at university will be much easier than mine.”

|

|

|