Madame Vastra stepped elegantly down the stone steps to the curious, almost hidden, room at the base of Tower Bridge. Her wife, Jenny, was less elegant but far more sure-footed. Not that Madame wasn’t agile and sure-footed when it was needed. But today she was the Veiled Lady, the aristocratic detective who was as fascinating to the readers of the Strand Magazine as Sherlock Holmes had been in recent decades. Her emphasis just now was on the ‘Lady’. Detective would come soon enough.

At the bottom of the steps was a plain wooden door, quite out of keeping with the elegant design of the bridge that was opened in glorious pomp only a year ago.

Standing beside the door was a uniformed policeman, and beside him was Detective Sergeant Michael Dowling. He was the unofficial connection between Scotland Yard and Paternoster Row as well as Millie the housekeeper’s ‘intended’.

Jenny wondered when Millie would be ready to move on from ‘intended’ to a more definite position. After all, the fact that Michael was actually an alien posing as a Scotland Yard detective was only a minor consideration in a household already occupied by a lizard woman from the dawn of time, her wife and a retired Sontaran Warrior.

“Good morning, Madame... and Madame.” Michael nodded respectfully to them both. “Doctor Braxton Hicks is waiting inside.”

Madame nodded at this news. Jenny was thoroughly impressed. Doctor Athelstan Braxton Hicks was a senior coroner, and one with a fierce reputation for apportioning blame for the unnecessary death of children, especially upon mismanaged public authorities. He was outspoken about the diseases of poverty that disproportionately affected the young of the East End. He also took issue with the number of young girls drawn into the ugly world of prostitution, too many of which ended up on his mortuary table as murder victims.

But those were all ordinary hazards of London life. If Madame’s presence was requested, this must be something more.

The fact that they were meeting at the Tower Bridge mortuary was another curious thing. The small room beneath one of the great towers was usually used to keep drownees pulled from the Thames until they could be identified and given Christian burial. Again, that was normal enough. It didn’t need Doctor Braxton Hicks’ expertise, let alone Madame’s.

The good Doctor was in his early forties, but pattern baldness and greyness in his mutton chop whiskers made him seem older. Jenny thought his deep brown eyes looked kind. His expression as he greeted his ‘guests’ was solemn, aware that they all had a difficult duty to perform.

Jenny looked around the mortuary, noting the easy to clean white ceramic tiles. She was aware of several linen covered bodies on tables, and an antiseptic smell that almost masked the corruption of the dead. Actually, it was slightly less nauseating than the smell around Smithfield meat market.

And she had seen dead bodies before. These occupants of the Dead Man’s Hole didn’t worry her too much.

Braxton Hicks pulled the cover from one of the tables. The body revealed appeared to be a child, which was sad, but again not unusual. Childhood was a dangerous time in Victoria’s London.

Then Jenny, along with Madame and Michael, looked closely.

It wasn’t a child. It was child-sized, but the shape of the body was that of a woman.

Not one afflicted by dwarfism, either. That would be very different proportions again. This was a normally formed female in miniature. Her face was elfin, the word came easily to Jenny. Her chin was pointed, the face almond shaped with brown eyes rather larger than expected. Her hair was dark brown and long. She had small breasts and as far as Jenny could see of the naked body, normal female genitalia.

“Is she a... pygmy?” Jenny asked. “Those African tribes that we hear about from missionary travellers?”

“She doesn’t have African skin pigmentation,” Braxton Hicks pointed out. “In fact, she is pale skinned enough to be albino, except her eyes and hair colourings contradict that hypothesis. The poor creature defies any racial or any other categorisation.”

“How did she die?” Jenny asked, glancing around the mortuary built with that prime purpose of storing victims of drowning. This unusual cadaver wasn’t bloated and blotched like a drownee would be even after a very short time in the Thames.

“Suffocation,” Madame said before Braxton Hicks could comment. “See the tiny pinpoint signs of broken blood vessels on her face. Doubtless when you perform the autopsy you will find congested lungs and an engorged right hand side of her heart.”

“I am sure you are absolutely correct, Madame,” Braxton Hicks said admiringly. “The examination of her internal organs will only corroborate that conclusion.”

“People CAN accidentally suffocate,” Jenny said, carefully. “But are we right in suspecting murder?”

“I believe so,” Braxton Hicks answered. “But a strange one. In my initial examination, I found this substance in her throat and nostrils. Enough to prevent her breathing.”

He pointed to a kidney dish containing what looked rather like half-chewed spinach leaves.

“An unusual murder method,” Madame commented. “I presume the unusual aspects of the case persuaded you to perform the autopsy in this unusual venue. Where was she actually found?”

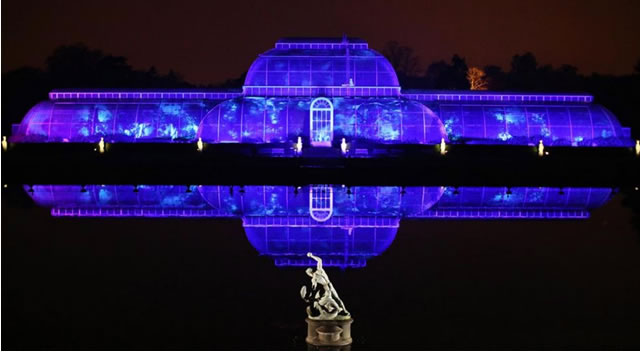

“In one of the greenhouses in the Botanical Gardens at Kew,” Michael answered. “One of the gardeners found her very early this morning. My superiors heard enough about the nature of the body to arrange this level of secrecy and put me on the case. Unusual deaths are my speciality, these days.”

He smiled as he said that. Madame nodded.

“I will observe the autopsy,” Madame decided. “But neither of you need to be present. Why don’t you go to Kew and see what you might find.’

Jenny was not squeamish, but not having to watch Braxton Hicks cutting into the poor creature to examine her lungs and heart was a relief. Michael thought so, too.

They travelled to Kew by water. Hansom cabs were always available to those who could afford the expense and horse drawn omnibuses travelled all the main roads of London. The underground trains had a station at Kew. But the quickest way to reach anything on the banks of the Thames was a rowboat handled by a sturdy waterman just as they had done since before William Shakespeare used them to reach his Globe Theatre.

It meant that they arrived at the back end of the Botanical Gardens, but that seemed to suit the middle aged man who met them, introducing himself as professor Alexander Curtis, junior specialist in exotic and tropical horticulture.

It struck Jenny that he was the least exotic person she had ever met: average height, brown haired, small moustache. His appearance was in total contrast to his job description.

He seemed just a little non-plussed by Jenny’s presence. Women were not, after all, employed by the Metropolitan police force, not even as stenographers.

“Miss Flint belongs to a charity concerned with the welfare of women and children,” Michael explained, though not until they were sitting in a small office with walls covered in drawings of plants where they were offered tea in a civilised way.

“The murder of a young woman within the Botanical Gardens is of great importance to my superior,” Jenny explained, handing the man a small, cream-coloured business card with the Paternoster Row address printed on it. He was disconcerted to see the name of the famous Veiled Lady.

“Well... An esteemed name indeed. I did not know that the Lady was especially interested in women and children. But that is... even so...” Curtis stumbled awkwardly over his words.

“Madame is especially concerned about the murder of the most vulnerable Human beings,” Jenny insisted. It was true, too. In the past, Vastra had been convinced that the whole ape-descendant race should be eradicated, but she had mellowed quite a bit.

“But... it wasn’t murder, surely?” Curtis finally answered with what seemed like genuine surprise and concern. “It was a tragic accident, I am sure. We are all quite distraught about her death within these grounds, but it must have been an accident.”

Did he seem too anxious to insist on an accidental death?

“We are treating it as murder,” Michael insisted. “The unusual location of her body only makes it more suspicious than a death in the dark streets of Whitechapel. Does anybody working here know who the young woman was?”

“Preliminary inquiries have been made by our own Garden Constabulary,” Curtis said, though that didn’t actually answer the question. “Of course, they are ready to co-operate with the Metropolitan detectives.”

“That is what we intend to happen, presently,” Michael said, and Jenny noticed a worried frown on the horticulturist’s face. He didn’t want that level of police attention within the Botanical Gardens.

“Why was she here?” Michael asked. “During the night, when the gardens are closed?”

“This is also a mystery,” Curtis said. “There are, of course, fences all around the gardens, and the chief role of the Constabulary is to patrol the grounds. But the fences are not impossible to climb, nor the patrols so constant that they couldn’t be evaded. On the other hand, we don’t often have trespassers. There are plants here of immense importance to science, but of no value to a thief.”

This was certainly true. Jenny knew of no dealers in stolen goods around the crime-ridden East End who would pay cash for greenery.

“Some of your plants must be edible?” she suggested. “Could the victim have been looking for food and accidentally eaten something poisonous?”

Curtis appeared to be thinking seriously of that possibility.

“If that is the case... Then it is tragic, but the Gardens are not at fault if somebody did something so foolish. We surely cannot be held to account.”

“We are not here to ascribe blame in that way,” Michael assured him. “But if it WAS murder, we cannot rule out employees or, indeed, directors of the Botanical Gardens - anyone who had access after the gates are closed to the public.”

“We have my dozens of people. Gardeners, cleaners, tour guides, as well as scientists and researchers dealing with obscure and rare specimens. Research continues long after the public have left. It will be a long process.”

“Nevertheless,” Michael insisted. “You will need to provide a list of employees. I will arrange for more men skilled in discreet interrogation.”

“Very well,” Curtis reluctantly agreed. “Please endeavour not to upset members of the public... And, it goes without saying we do not wish this to be publicized in the newspapers.”

“Nor would the Metropolitan Police Service,” Michael assured him. “Though if murder was done here by an employee, it will be difficult to hide the matter. At least I can assure you no revelation will come from the police, or Miss Flint’s organisation.”

That would have to do. A life had been lost. The reputation of a London attraction was less important.

Keeping it out of the papers was not very likely, though, Jenny thought. Cleaners and gardeners were likely to be swayed by a small gratuity from a journalist. The story would be out soon enough.

“While we wait to begin interviews, I shall want to see the place where the body was found.”

Did Curtis hesitate then? Was there a strange grimace on his face? Was he hiding something?

But he recovered his poise and led them to one of the many beautiful wrought iron greenhouses designed by clever men twenty years before Jenny was born.

It was very hot and humid inside the greenhouse with tinted glass panes that diffused the natural sunlight. The plants were all huge, not merely tall like trees, but leaves and flowers the size of dustbin lids. One plant had vicious spines resembling daggers, another had roots as thick as a man’s arm lifting clear of the soil it grew from, and all a hyper-real kind of green that didn’t quite seem natural.

And so hot and clammy Jenny thought it must be something like the prehistoric world Madame had once lived in. She described it sometimes when in a nostalgic mood.

“She was found here,” Curtis said pointing to a depression in the soft, green surface that was at ground level but a thick, springy, water-sodden moss, not grass.

Yes, a small body could have lain there, curled up in death. The disturbed depression in the moss was obvious.

But none of the strange plants around there resembled the leaves found in the victim’s mouth and throat. Jenny thought it unlikely that she had wandered far with her windpipe blocked.

But why would Curtis lie?

Because she actually died somewhere else – somewhere dangerous, somewhere so secret he wasn’t even prepared to reveal the secret to Scotland Yard.

At a telephone message from Michael, a whole team of police officers arrived to conduct the bulk of the interviews with the staff. Michael, with Jenny in attendance, concentrated on the senior staff, the scientists who spent their days in humid greenhouses, nurturing unusual plants. They all seemed to resent being asked to leave their plants and talk to mere humans. A dead woman actually seemed less important to them than a new kind of orchid or a rare Amazonian fern.

And none of them had anything to say that explained how she could have died within the Botanical Gardens.

Or didn’t WANT to say anything, which was a different matter entirely.

“Far be it for me to say,” Michael commented as he and Jenny headed back to Paternoster Row to discuss the lack of findings with Madame Vastra. “But did most of that lot seem a bit potty?”

“The one who thought humans eating vegetables was murder....” Jenny singled out.

“That one, for certain,” Michael admitted. “And the one who advocated forced sterilization of working-class people because the human race used too much of the oxygen that his precious plants produced. He made me want to eat a large salad for tea, served in my very own oxygen tent.”

These particular two were brothers, professors Edgar and Elgar Metcalf. They were Professor Curtis’s immediate superiors in the long-windedly titled department of ‘Unique and Previously Unidentified Plant Species’.

They had been angry that they had been called to make statements, being sure Curtis ought to have been enough of a representative of their department. They were not happy about Jenny's presence either. Women were of no value to them. To be called a frivolous breather of air was just about the oddest insult Jenny had ever received.

“Even the more normal ones were obsessed with their precious plants,” Michael added. “And they all wanted rid of us and our poking around.”

“Do you think one of them murdered that poor woman?”

“I wouldn’t rule it out,” Michael conceded. “But proving it...”

That, indeed, was the problem. Neither had an answer.

Nor did Madame, who was already home when they arrived.

“There is a little more revealed by the autopsy of Anna Greenwood,” she said over a pot of tea in the drawing room.

“Anna Greenwood?” Michael and Jenny both asked.

“Despite my general thoughts about your ape-descended species,” she explained. “I am in agreement with Doctor Braxton Hicks that calling her ‘the victim’ was too cold. Hence the name which he put on the paperwork. Anna is about twenty-five years old and had given birth at least twice. Her death was, of course, caused by suffocation. Her stomach was found to contain more of the leaves already found in her mouth and throat, apparently forced down with some pressure. A lot of the leaves were pushed into her stomach while others constricted her lungs.”

“Poor woman,” Michael commented.

“These leaves,” Madame continued, pointing to a bell jar containing some greenery. “Are a type that hasn’t grown on this planet for at least two million years. Look at them closely.”

They looked. They gasped in astonishment.

The leaves were moving, quite of their own volition, folding and unfolding like hands opening and closing.

“They’re alive?” Michael queried. “Not... Not sentient, surely?”

Words like sentient used correctly were what set Michael apart from most ordinary policemen, even in the detective department and endeared him to Madame as above the herd of stupid humans.

“No. Not sentient,” she agreed. “My people called them strangleweeds. We carefully avoided contact with them, even burning any large growths of them close to our habitats.”

“You know what they are, then?” Jenny queried.

“I do. But such a species could not have survived the ice ages that occurred while my people hibernated. The plants should have died out in the extreme cold. It is possible that seeds survived, buried in the ground. Some fool must have found them on some misguided scientific expedition... Grown them in the hot, humid conditions of the Kew glass houses. Somebody must know how dangerous the weeds are, but they nurtured them. The fools.”

Jenny and Michael thought of the plant obsessed Metcalf brothers and professor Curtis’s obvious attempts to hide something.

“I can’t arrest a plant for murder,” Michael said with a deep sigh. “And it would be difficult to hold the Professors accountable. And we still don’t know how Anna was involved in the first place.”

“Which is why we’re not giving up on this,” Madame insisted. She looked about to outline something devious, but Millie came quietly into the drawing room, followed by a barefooted and slightly grubby boy.

No, not a boy. Like Anna, this was an adult of small proportions, pale complexioned and anxious looking.

“He has a message for Miss Jenny,” Millie explained. The small man stepped close and held out a folded note. Jenny took it and read, then handed it to Madame.

“This is Henry. He will bring you to Kew after eight o’clock . It is time both of the Garden's secrets were explained. When you know, do what you feel necessary.”

It was signed by Professor Curtis.

“This simplifies things,” Madame said. “I had planned a break-in.”

“You shouldn’t say that in my hearing,” Michael reminded her.

“Indeed,” Madame agreed. “Which is why we won’t trouble you further. You may take Millie for an evening at the theatre, a good dinner, whatever the two of you enjoy doing together. Present any expenses to me, later.”

“Dinner and a show sound good,” Michael agreed. “I shall endeavour to have her home by... midnight, shall we say?”

Millie was quite happy with the idea. Before putting on her best going out dress and hat she gave Henry a meal and made sure he was comfortable.

“He doesn’t talk,” Millie noted. “But he’s not daft or anything.”

“Doctor Braxton Hicks thought that might be the case,” Madame said. “He thought Anna’s throat was wrongly developed for speech. Henry is clearly related to her.”

“How many are there?” Jenny wondered aloud. “If Anna had children as the doctor thought.... A whole family? A tribe? A village? But where do they live? How could anyone so different live in London and not end up working in a circus?”

“I think they are certainly one of Kew’s secrets,” Madame said. “One, I hope, we will understand better later this evening.”

Michael and Millie left for their evening at the theatre before Strax brought the carriage around. The house was left in young Joe’s charge as Henry pointed the way back to the Botanical Gardens as if it was a place he knew intimately and was relieved to be returning there.

They had expected to enter the premises by a quiet backway, and were surprised to come, instead, to the main entrance. Henry nodded emphatically when asked and brought them to the brick-built campanile by the public gate. The door was unlocked and they were further surprised to be led down a spiral staircase inside the curiously Italianate building.

“What is this?” Jenny asked, noting how her voice echoed along with the rattle of Strax’s heavy feet on the steps.

Henry used some odd hand gestures to try to explain, but nobody understood until they reached the bottom of the staircase and found themselves in a brick-lined tunnel wide enough for a small cart to pass along.

Or a narrow guage railway car, Jenny thought, noting, by the light of a paraffin lamp hung from the ceiling, rails set in the concrete ground.

“There is nothing sinister about the tunnel,” said Professor Curtis, stepping from an alcove that concealed him until he made himself known and opening the slide on another lamp. “Though it is not commonly known by the visiting public. It is simply a quick way of bringing coal to the furnaces that heat the great Palm House and the other hothouses. These pipes running along the wall bring the fumes from the same furnaces safely back to the chimney concealed in the campanile.”

“How enterprising,” Jenny remarked dryly. “Great British engineering at its best.”

“Just so,” Curtis commented, not noticing Jenny’s slightly sarcastic tone. “But this isn’t one of the secrets I mentioned.”

He stepped back into the alcove and pressed an apparently random whitewashed brick in the back wall. The whole moved back with a scrape of stone on stone to reveal another passage.

“Come quietly from here,” Curtis said. “They don’t care for loud noise, and even footsteps echo in the tunnels.”

That stopped a lot of questions as Henry took the lead again, followed by Curtis, then Madame Vastra and Jenny with Strax in the rear. He was doing his best to keep his footsteps quiet, though his biggest worry was that this new tunnel was much narrower than the one built for the coal transport. His elbows bumped the whitewashed walls as he crept along.

The tunnel opened eventually into a room at least the size of the drawing room at Paternoster Row, though it felt smaller because it was full of armchairs and settees – more than a dozen of them.

And all of the seats were occupied by small people, male and female. Even smaller ones, children, sat on thick fireside rugs, though there was no fireplace.

The room was very warm without open fires. Jenny wondered if it was heated by the same furnaces that served the Palm House.

The small people looked sad. They clutched each other’s hands as if giving each other comfort.

They were polite to their curious mix of visitors. Three armchairs were given up for the guests. Jenny noticed Strax sitting on a settee and immediately being besieged by the tiny children, sitting next to him and even climbing on his lap. He looked bewildered. As a warrior of Sontar he could have snapped their little bodies in half, but his training in Human behaviour meant he had to put up with this invasion of his person.

“These are the Dannan,” Curtis explained in a low, calm voice. “Some of them, anyway. As I understand it, Dannan is an Irish word meaning ‘people' and I have no idea why a sub-species of humans using that name for themselves have lived in caves and tunnels they excavated for themselves since long before the Botanical Gardens were founded above them. Nobody seems to have known about them until the coal tunnel was begun in 1848, but the then directors of Kew, having found them, swore an oath of secrecy, and promised to protect them. Until yesterday, that promise has been kept. Even our path sweepers and toilet cleaners, people who might be inclined to take a bribe from a newspaper writer are happy to keep the secret. The death of Ainya in what should have been a safe haven distressed all of us equally."

Not quite everyone, Jenny thought, thinking of the Metcalf brothers who resented the oxygen breathed by humans, even small ones.

“You must understand that much,” Curtis went on. “We had to dissemble to protect the Dannann. But it hurt us as much as it hurt them.”

Curtis looked genuinely stricken. This, Jenny thought, was his real face. Not the mask of lies from earlier in the day.

“Her real name was Ainya?” Madame asked. Both times the name was mentioned a kind of wordless sob passed around the Dannan, their way of mourning one of their own. The coincidence that Doctor Braxton Hicks had chosen Anna as a name for the dead woman seemed just right.

“It was,” Curtis answered. “Which reminds me... if I could prevail upon you to help get her body discreetly returned to us. The Dannan have their own long tradition of burying their dead in deep caves, away from their living quarters, but close enough that the dead are still part of their community.”

Madame promised to do just that. Funeral rites of a kind were important to her own people as much as it was to the ape-descendants. One of the few things they had in common.

“That is how the proto-humans who first gathered in social groups lived,” Madame remarked about the Dannan’s own funeral customs. “If you paid some interest in your own species as well as plant life you would know of archaeological evidence in Scandinavia and parts of northern Scotland. Which suggests that communities like the Dannan are much older than your ‘civilisation’ above ground.”

“Communities?” Curtis queried. “Plural... Do you mean....”

“The Dannan are the first such tribe I have met,” Madame said. “But I have heard stories. There may be a similar group under Brick Lane in the East End. There is such a mix of immigrant peoples in that neighbourhood I think they are probably able to get along without arousing any suspicion of their subterranean life.”

“I’ve never heard of a Brick Lane community,” Curtis admitted. “The Dannan seem to be a ‘tribe’ in the sense we hear about from African missionaries. Loosely related, though not so closely as to cause problems of inbreeding. They look after each other rather better than we do above ground - without workhouses and orphanages. “The two children sitting on your wide friend’s knees are Ainya’s children. They are grieving the loss of their mother, but the Dannan will take care of them. It is natural to them to do so. Their elderly are comforted, the children protected. The adults work....”

“At what?” Jenny asked.

“They work here at Kew. Any job that needs doing. Especially tending to the plants. They have always been good at that. They grow their own vegetables underground, using a secret process they won’t even share with me, though I have begged them. And after the park is closed they scuttle about doing all kinds of work. Ainya and Henry, as well as a couple of others, are my best assistants in the exotic greenhouses.”

“Which makes Ainya’s death by strangleweed even less likely to be an accident,” Madame pointed out. “She must have known they were dangerous.”

“Strangleweed?” Curtis queried. “That’s not what Edgar Metcalf calls them. He named them Cuscara Metcalfia.... after himself. He thinks they are a great advance in plant science. But I’ve seen what they do... to rabbits and other small animals he feeds to them. Strangleweed is a good enough name for the filthy things.”

“The fool has cultivated them?” Madame asked.

“The seeds were found in the frozen tundra of northern Russia. I was as excited as the brothers were to find they were still viable. To grow something that last saw the light millions of years ago... Yes, it was remarkable. But what grew from those seeds was an abomination against God and against nature. And now they’ve killed... As I feared they would. Killed an innocent woman of the Dannan. I was told to get rid of the police... Put them off the scent. But the Metcalf’s are wrong. Scientific research that kills innocents like Ainya... They can’t be allowed to continue. That’s why I knew I had to tell you the truth.”

“Show me,” Madame said. “Show me where these insidious plants are growing.”

“Of course,” Curtis said. He stood. Madame and Jenny followed him. Strax didn’t. He still had knees full of small children. He gave a rather sheepish look and said he’d be along shortly.

They retraced their path back to the coal tunnel and continued along to the fiercely burning furnace which was manned, they noted, by more of the Dannan.

“It is one of the ways they earn their keep,” Curtis explained. “They’re happy to do their bit. You should see them pulling the coal carts. They have the strength of full-grown men in their little bodies.”

“It... Sounds a bit like slavery,” Jenny suggested.

“No, absolutely not,” Curtis assured them. “It has been an agreement between them and us since they were first discovered. They don’t want money. Food they can’t grow for themselves, and clothes, the old furniture you saw... Some few luxuries. They like fruit cake... And soap. They never had anything like it before we knew them. They treasure their own individual bars of Pears Soap. And in return they give us their time and their labour.”

“I hope that is true,” Madame said with pursed lips – a gruesome expression for a lizard lady. “I intend to check regularly. I will keep the secret, of course. I have no wish to see those people exposed to the decadent city above their heads and the greed of men. But if I feel there is any sort of exploitation, you will incur my wrath.”

The very tone of her voice made it clear that her wrath would be a dangerous thing to incur.

“My word, Madame,” Curtis assured her.

Not far from the furnace room, another spiral staircase brought them up through a wide trapdoor to a huge wrought iron greenhouse. It was not the famous Palm House the furnaces were built to heat up, but clearly this one made use of the same system of hot water pipes.

It was stifling hot and so humid that condensed water dropped from the cooler glass roof panels like a perpetual shower.

“Yes, this was how the forests were... Where the strangleweed thrived,” Madame said. She sounded wistful, as if remembering something with fondness. But her face hardened as she looked at the plants that surrounded them.

They were like vines, twisted around the boughs of ordinary trees, hanging down towards the ground, drinking the ever present water with their rustling, grasping leaves.

The air was full of the sound of the weeds moving. It was, at first, no stranger than leaves blowing in a breeze.

But there was no breeze.

“How much of it is there?” Madame asked. “All this from a few frozen seeds?”

“At first, there were only a few, rather straggly vines. But... Like I said... Edgar and Elgar... FED them.”

Madame began to say something, but was cut off by a squeal from Jenny.

Jenny squealing was unusual. She was as brave as one of Madame’s own people in the face of terrible foes.

But the strangleweed was curling around her waist, pinning her arms.

“Keep still,” Curtis yelled. “If you struggle it will only grip harder. Try to relax,”

Jenny’s response to being told to relax was a very rude word used mainly in disreputable spaceports in the Orion sector. She had learnt it from Strax.

Then even alien curses were cut off as a weed clamped over her mouth.

“No!” Curtis cried out. He wielded a copper pot with a pump and spray nozzle. The liquid that sprayed from it was pungent and it clearly irritated the strangleweed. It shrank back, releasing its hold on Jenny who fell back into Madame’s arms.

“It is an alkaloid used as a fertiliser for some plants. I found out some time ago that these damned things are repelled by the mixture.”

“Do you have more of the substance?” Madame asked. “Enough to kill the lot?”

“No,” Curtis admitted. “I wish I did. I would have used it before now to make an end of these abominations.”

“No doubt you would!” cried a harsh voice. Elgar Metcalf stalked towards Curtis while his brother tried to take hold of Madame.

That was his last mistake. Nobody laid hands on Madame Vastra without her permission. With two flicks of her wrist, he was thrust away...

... Straight into the grasp of a thick vine of strangleweed. He screamed and fought, but the vine tightened.

Curtis tried to help. He sprayed the vine with the alkoloid liquid, but it didn’t seem to be working, or not working fast enough.

“Urgggh,” Jenny remarked as she tried not to watch the death of Edgar Metcalf but found herself incapable of turning her head aside.

Even Madame, who had allegedly eaten the heart of Jack the Ripper, made a tiny repulsed noise.

“What have you done! My brother was a friend to plant life.” Elgar Metcalf stormed forward. He grabbed Curtis by the neck and started strangling him. “You couldn’t keep your wretched mouth shut, you fool. You’ve killed my brother and damned us all... Just because of one unimportant, expendable flesh woman. You... You...”

Jenny and Madame together pulled him away from Curtis, who staggered and gasped for breath. Then, while everyone was wondering what to do next, Strax came up from the staircase and stalked past everyone.

“Get out,” he ordered. “Get below. NOW.”

Curtis grabbed Elgar Metcalf by the collar and thrust him down the trapdoor ahead of him. Jenny and Madame followed quickly. At the foot of the staircase they looked up anxiously, waiting for Strax. He wasn’t immune to the strangleweed. If the pernicious vines blocked his probic vent they could kill him as surely as any Human.

At last, he hurried through the trapdoor and turned to hold it closed, not trusting the bolt that slid into place.

An explosive whoomph vibrated the trapdoor. Strax held tightly as the bolt and hinges buckled. He didn’t let go for several minutes when the vibration ceased along with the noise of destruction above.

“What WAS that,” Madame demanded as Strax joined them at the bottom of the staircase.

With a somewhat guilty tone he described a grenade made from beer bottles full of phosphorus chemicals and lamp oil. When the glass container shattered and oxygen mixed with the chemicals it flared hotly and destroyed all in its path.

But only for a very short time and a very small area. By the time they all emerged from the coal tunnel at the Campanile the Botanical Gardens Constabulary confirmed that there had been a fire in one of the hothouses but no other buildings were affected and the London Fire Brigade were simply checking that the structure was not liable to collapse.

No body had been found in the debris. What the strangleweeds had left of Edgar Metcalf had been utterly destroyed by the fast, hot phosphorus fire.

“You...” Curtis turned on the surviving Metcalf. “Tomorrow, you will resign on behalf of you and your brother - on what grounds, I don’t care. Take a a packet boat to the furthest reaches of the Empire and never mention any part of your career at the Botanical Gardens. If you do not do this willingly... My friends here will help make sure you do it by force.”

Not surprisingly, after glancing once at Strax’s dark face and Madame’s stern expression, Metcalf agreed to that ultimatum and hastily disappeared.

“You go back to the Dannan, now, and reassure them,” Madame said to Curtis. “That is one secret of Kew that shall be protected now that the other is destroyed.”

With that, Madame and Jenny withdrew. Strax had brought the carriage around for them.

Before getting in, though, Madame had a word to say to Strax.

“When did you make these dreadful bombs?” she asked. “And why were you so easily able to lay your hands on one of them?”

Strax admitted to making the incendaries in the cellar. He kept some of them under his driver’s seat in case of need.

“So all this time, we have travelled along London roads full of bumps and potholes with fragile bombs sitting there over our heads?” Jenny pointed out

.“But they WERE needed,” Strax protested.

“Yes,” Madame admitted with a resigned sigh. “Very well. But we will be having a very long talk about safety tomorrow.”

“Yes, Madame,” Strax responded with surprising humility.

“And I want to know how you became favourite uncle to the Dannan children,” Jenny said. Strax, not surprisingly, had no answer to that, but smiled deprecatingly - if such a term could be applied to a warrior of Sontar.

|

|

|