Jimmy Forrester wriggled uncomfortably in his latest ‘period costume’. Granted, it was Victorian, not Tudor. Trousers had been invented. He positively hated the ‘hose’ he had to wear on visits to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

But mid-Victorian clothes were almost as bad, particularly in late autumn when long underwear had to be worn under the trousers, shirt, waistcoat and topcoat of a gentleman.

The underwear was what was trying to eat him alive as they travelled by carriage through the streets of London in October of 1878. His attempts to relieve himself of the discomfort were incurring the wrath of his companions, though.

“Stop it,” Vicki warned him. “Victorian gentlemen don’t stick their hands inside their jackets and scratch their arms.”

“These ‘foundations’ as you call them have fleas… or maybe itching powder in them,” he complained.

“They came from the Wardrobe in MY TARDIS,” Vicki responded. “They have neither. Besides, I don’t know what any man has to complain about. At least you’re not wearing CORSETS.”

By her side, Sukie verbally applauded that sentiment.

“You both look elegant,” Earl remarked, shifting the subject away from contemporary men’s underwear to the silk satin day dresses the girls were wearing. He disliked the woollen ‘long johns’, too, but he had travelled in the past extensively and was used to the discomforts of contemporary clothing.

“Well, of course we do,” Sukie remarked. “TARDISes are female. The Wardrobe will always have great stuff for us. Anyway, I think we’re here.”

The carriage pulled up outside the elegant Palladian style Burlington House on Piccadilly. Earl and Jimmy exited the vehicle first in order to help their ladies down. Both were feminist enough to want to do it themselves, but at the same time they enjoyed the attention of the men. Besides, corsets, bustles and wired underskirts combined to make independence difficult when alighting from coaches.

They passed together through the archway into the wide courtyard round which the house was designed. By 1878 it was established as the home of science and learning, with four major societies having their headquarters there – the Geological Society, the Linnean Society, Royal Astronomical Society and the Society of Antiquaries.

Earl, in his exploration of history, had managed to get himself elected as a junior member of all four of those societies. It was in that capacity that he had been able to bring his friends on a crisp, cold afternoon to a lecture in the library of the Lineman Society.

Jimmy had not been thrilled by the plan. He had pointed out several times that a talk about plants by the SON of Charles Darwin was not his idea of how to spend a Saturday afternoon.

Vicki had pointed out that it was a Wednesday afternoon in 1878 and that her father, The Doctor, claimed to be a very good friend of Darwin senior and had proof-read On The Origin of Species for him.

“He would!” Jimmy had replied, but not within Vicki’s hearing.

They turned to walk across the cobbled square to the west, Piccadilly facing, wing occupied by the Lineman Society. As they did so, a woman in a severe dark blue dress buttoned up tight under a rather chubby chin handed leaflets to them all. She was handing everyone leaflets. As they stepped into the west wing a gentleman in front of them commented loudly and disparagingly about the imposition.

“Time was printing was reserved for those with something worthwhile to say,” he complained. “Now any imbecile can produce ill thought out nonsense for pennies.”

He thrust the leaflet into the hands of a society steward and told him to dispose of the ‘nonsense’. Vicki, Sukie and Earl all got rid of theirs. Jimmy stuck his in his trouser pocket.

In truth, the lecture, even enhanced as it was by magic lantern slides, was dull. It was about phototropism, the movement of plants to face sunlight, which was fascinating to Francis Darwen and his father, who were collaborating on a book due for publication in 1880. Perhaps it was of interest to their fellow Linneans, but the four time travellers really did have a hard time keeping their attention on near identical pictures of sundews with twisted stems following the passage of the sun across the sky.

“Kind of hard to get excited when we’ve visited planets where plants follow US around,” Sukie admitted telepathically. Earl agreed with her.

Vicki didn’t take part in their silent reminiscences about wild planets with mobile plantlife. She didn’t like talking telepathically when Jimmy couldn’t join in with them. Instead, with a very subtle adjustment of her demure, ‘sitting up and paying attention’ position, she nevertheless leaned close enough to her boyfriend to read the leaflet he had kept. She was surprised by the subject matter, and deeply sceptical, but it held her attention far more than phototropism.

When the lecture was over, they found themselves invited to take tea with Mr Darwin junior and couldn’t think of a polite way of getting out of it. They endured an hour in the second floor dining room where women were only allowed if accompanied by members of the Society. Vicki managed to steer the conversation away from phototropism by talking about a visit to the Darwin family home, Downs House in Kent, when she was nine years old. She remembered the garden and the greenhouses fondly and listening to her father and the great Charles Darwin discussing evolutionary theory under sunshades on the lawn. She remembered understanding all of it because she had already started her advanced education. Of course, she didn’t tell Charles that, and she didn’t tell Francis, either.

Vicki’s reminiscences and an invitation to ‘visit again very soon’ got them through tea. At last they were free of obligations. Jimmy produced his leaflet and announced that he was taking them to the next lecture.

“The Southcottian Society and the End of Times,” Sukie read scathingly. “What is a Southcottian and when do they think the End of Times is coming?”

“They’re a sort of religious group with an obsession with some sort of future prophecy,” Jimmy answered. “Yes, I know, nutters. But you dragged me here to listen to all that stuff about plants. Now I’m dragging you over to the Society of Antiquaries to find out what this lot are really on about.”

Put that way, nobody could really refuse. Well, they could, but Jimmy would have the right to make the trip home by TARDIS really miserable for them all.

They crossed the courtyard of Burlington House and presented themselves at the Society of Antiquaries, where they were a little grudgingly directed to the Library.

“The Southcottians seem to have got the use of the Library under false pretences,” Sukie explained after looking deeply into the steward’s eyes for a full ten seconds. “They said it was an historical lecture about eighteenth century evangelism. It turns out its mostly about some woman who made a prophecy about a coming apocalypse.”

“But they still let it go ahead?” Earl queried. “They didn’t tell these weirdos to sling their hooks?”

“Apparently enough secret Southcottians are members of the Society to block any attempt at slinging... or hooking for that matter,” Sukie confirmed. “I’m actually intrigued, now. Let’s have a look.”

The library with collonaded balconies and lots of natural light from the roof and side windows was a pleasant location for a lecture. It was unlikely that the seats were being filled with people who came to learn about the prophecy of End Times, though. Rather, they had gathered to debunk the story being presented.

“The sciences and philosophies usually studied by the Burlington House Societies tend towards ‘Reason’ and ‘Logic’,” Earl commented as they tried to settle amongst a decidedly restless crowd. “A great many of the Fellows and Members are atheists who cling to science rather than religion. They’ve come to heckle.”

“This library contains one of the copies of the Magna Carta,” Vicki said. “They really ought to have more manners, regardless of what they think.”

The crowd did quieten down a little as a gentleman called Isaiah Westingholme stood on a small dais beside a portrait of a plump lady wearing a large bonnet. She had a faint smile and round cheeks like a none too politically correct description of the ‘fat, jolly cook’ in some fictional kitchen.

But her story was far less homespun.

She was Joanna Southcott, a farmer’s daughter from Devon who, having grown up in a devout Church of England home where Bible reading was a daily occurrence, she had been a quiet, industrious and unremarkable country woman until she reached her mid-forties. It was then that she began to declare herself a prophetess, preaching about her visions all around Devon and even as far as London. She had claimed to have a special insight into the Bible, particularly the Book of Revelations.

That was all very well. People with ideas like that sprang up all the time. But what made Joanna unusual was that, in her sixties, having by then attracted a small following of believers, she had said that she was pregnant with a new Messiah who would save 144,000 worthy people from the apocalypse and give them eternal life.

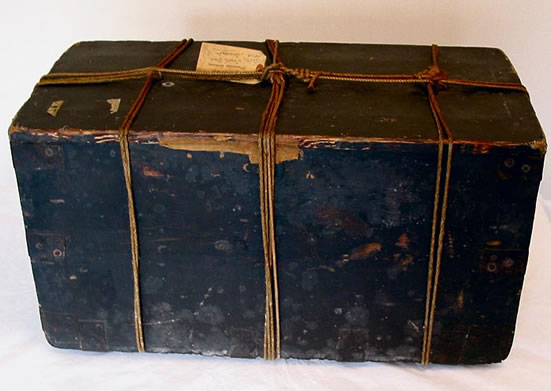

Needless to say, a woman of sixty-four years of age in a time long before fertility treatments existed, did not give birth to any sort of baby. Instead she died, leaving her followers a prophecy that the world would end in 1814. She also left a sealed box that she claimed to contain words of wisdom that should be revealed only at the time of crisis, and then only in the presence of the twenty-four bishops of England and Wales who would be able to understand how to avert the peril.

The world had not, of course, ended in 1814. But that had not been the end of it. Belief in Mrs Southcott and the wisdom contained in her mysterious luggage had steadily continued. As Sukie had noted, many believers were educated men who joined learned societies, which allowed them to hold lectures in places like the Library of the Society of Antiquaries, thus lending a veneer of authority and veracity to their contentions.

That veneer was well and truly burnt off by the learned and mostly atheist or at least sceptical listeners. Men who were contemporaries of Charles Darwin and Thomas Huxley were hardly likely to support ideas like these. Even those who were still church-goers felt that Mrs Southcott was a false prophet and almost certainly a charlatan who had allegedly sold pieces of paper with a ‘seal’ on them to those who wished to be among the 144,000 saved. Needless to say, this was very much against Church of England teachings about how to get to Heaven.

But Isaiah Westingholme and his fellow Southcottians stood their ground against the intellectual arguments and would not be swayed from their main point.

The apocalypse was almost upon the world and the bishops had to be assembled to avert it.

“Was 1879 significantly more catastrophic than any other year since humans started counting them?” Vicki asked later when they were in a carriage heading back to the freight yard of Waterloo Station where they had parked the TARDIS for the day. “I mean, AD 79, when Vesuvius erupted and Pompeii and Herculean were destroyed was pretty apocalyptic. Or BCE 1540 when Mount Thera erupted on Santorini, destroying the Minoan civilisation and causing devastation right across Europe and North Africa was a REALLY bad year. There is even a theory that it caused the biblical ten plagues of Egypt, which was certainly apocalyptic for the Pharaoh. But… next year….”

“It was a bad time to be a Zulu,” Earl commented. “After Isandhlwana and Rourke’s Drift the British massacred them in retaliation.”

“The Tay Bridge collapse was a bad time for Scottish railway travellers,” Sukie added. “And bridge builders.”

“John Henry Newman became a Cardinal,” Earl added, reaching for significant events in his memory. “For anyone – like me - who went to the college named after him that was a bit disastrous.”

“E.M. Forster was born in 1879,” Vicki said with a soft smile. “Not a disaster, just a fact about that year. He’s one of my favourite authors. Mum and grandma Jackie like him, too, but more from the films than his books.”

“Fulham F.C. were founded,” Jimmy said, not to be left out.

“Oh, well, that would be it, then,” Earl commented. “That’s a sign of the End Days if there ever was one. 1879 is definitely a year of apocalypse.”

They all laughed, shaking off a little of the apprehension the so very earnest Southcottians seemed to have infected them with despite their obvious scepticism.

“This sort of thing pops up all the time in history,” Earl continued, if only to stop the girls worrying too much. “Not so much in our time. We do have more of a grasp of science. But every so often there are these seemingly random predictions. I visited New Year 2000 a few times and there were a lot of people convinced it was the End. Then there was an American a decade later going on about a ‘Rapture’. He was going to take his followers to heaven in a space ship while the unbelievers burnt in the everlasting fires. After the apocalypse failed to happen and he disappeared along with millions of dollars from his followers most of them stopped believing.”

“You would have thought these Southcottians would have felt the same way, by now,” Jimmy suggested. “Although there is still the mystery of her… box.”

Jimmy and Earl both got elbowed in the ribs in perfect synchronization.

“Dirty jokes about women and their boxes are taboo,” Sukie informed the men severely. “And stop smirking every time the word is mentioned. A box is just a container to keep things in.”

The trouble was, drawing attention to the joke only made it funnier. Earl and Jimmy both shook with repressed laughter all the way to the station and any intelligent discussion of the subject was impossible. Vicki and Sukie ignored them and talked about the struggle of Victorian men of science like the Darwins to reconcile their new philosophies with the Christian faith in which they were all brought up. Many of them wanted to stay within the teachings of the Church of England even though they believed in evolution or had collected dinosaur fossils and knew that the planet was millions of years older than the Bible suggested.

“Daddy says it is something unique about human beings,” Vicki observed. “On most planets either science or religion is accepted wholly – not both. Except worlds like Tigella where two different sects – the scientific Savants and the religious Deons - live separately on the one world. I’m not sure if Daddy thinks humans are better or worse than those species for trying to balance the two. I think, after meeting people like Francis Darwin, I believe the former. Belief in a God doesn’t have to deny science or vice versa.”

“You’d better tell it to the Tigellans,” Sukie commented. “They tend to break out into holy war all the time. Come on, we’re at the station. Let’s get back to the TARDIS. How about supper at the Omicron Psi Orbital Restaurant before we head home?”

The idea pleased everyone. The restaurant with a revolving floor giving all round views of a constellation was a saved co-ordinate from previous visits. The journey took just long enough to change out of the Victorian clothes.

Usually, Jimmy found the experience fascinating. He enjoyed ordering pre-meal drinks at a bar managed by an eight-armed Octarinian who could mix six cocktails at once while taking orders for the seventh and making a rude gesture to a stroppy customer who didn’t include a tip in his bill.

Tonight, he was so distracted he almost forgot the tip and risked bringing the gesture on himself. Even when they were seated and ordering their dinner he was looking down at his smartphone screen and thumbing through pages of information.

“Jimmy,” Vicki hissed. “Don’t be so rude. Whatever that is, it can wait.”

“I’m not sure it can,” he answered. “We’ve all had a good laugh at the Southcottians and their nonsense… but I think something bad might have happened to them all in 1879.”

“What do you mean?” Earl asked.

“Look….” Jimmy passed his phone over the table, eliciting annoyed ‘tuts’ from the two girls. Earl read the article then reached into his pocket for his hand-held computer. After a few minutes of frenetic scrolling he was frowning with concern.

“There’s something odd, here,” he confirmed. “I think….”

“I think it can wait until we finish eating,” Sukie cut in. “We’ll talk about whatever it is back in the TARDIS. Come on, guys.”

They did their best, but now both men were distracted and really didn’t enjoy their food. They kept looking at each other and frowning. If she didn’t know that Jimmy had no telepathic skills Vicki would have suspected him of carrying on a secret discussion.

“This is worse than when you were giggling about Joanna’s Box,” she complained. “Go on, say something about the wretched thing.”

“The box is a red herring,” Earl informed everyone. “It’s in the British Museum archives. It’s been there since the mid-twentieth century. Nobody even cares enough to scan it with an MRI let alone open it. Dozens of major crises have come and gone without the bishops assembling to ponder its contents.”

“I was wondering about that,” Vicki admitted. “Even if it were true… it’s like the thing about King Arthur returning in the time of England’s greatest peril. How would he know what the greatest peril was? What if something seemed like the greatest peril but there was a worst one to come?”

“Don’t,” Earl told her. “If you start thinking that way, you’re halfway to believing it. Just keep telling yourself it’s nonsense.”

“Neither King Arthur nor the Bishops were any help with the Daleks invasion or the Dominators,” Sukie noted. “That bit is complete hogwash. I want a slice of Omicron Psi Super Chocolate-Strawberry Gateau with extra cream for dessert. The mystery of how it tastes so great but has no calories is way more intriguing. I know at least twenty-four women who would gather if that recipe was in Joanna Southcott’s Box – including my mum and grandma Jackie.”

Everyone laughed, as she hoped they would. They finally managed to concentrate on their meal for a while, even lingering over coffee and watching the Octarinian single-headedly deal with three Venturans who had drunk too much and started to be a nuisance to other diners.

Well, ‘single-headedly’ wasn’t the exact word for it, but it was interesting to watch anyway.

“Look,” Jimmy said when they were back aboard the TARDIS but still parked on the shuttle deck of the restaurant. “All of Isaiah Westingholme’s group disappeared one night in 1879. He was found in Green Park badly burnt. He was lying next to a huge patch of burnt grass and smouldering trees. He died without speaking a word. All the others… there were missing person reports and after a few years their families had them declared dead….”

“How many people?” Sukie asked. “Not one hundred and forty-four thousand?”

“Thirty-nine,” Jimmy replied. “A bit short of the magic number.”

“Why that number, anyway?” Vicki asked.

“It’s biblical – the total number to be saved from each of the twelve tribes of Israel after the Day of Judgement,” Earl answered. “Twelve thousand from each makes 144,000.”

Everyone looked at him quizzically.

“I told you I went to a college named after a Cardinal. We did stuff like that. I guess nobody else did?”

“Vicki and I were taught by The Doctor to respect all human religions, but we didn’t really go into a lot of detail,” Sukie explained.

“I skipped R.E.,” Jimmy admitted.

“Well, it doesn’t really matter at the moment,” Earl said. “What is really odd is that Jimmy has all the information about Isaiah Westingholme and people disappearing, but my hand-held and the TARDIS computer don’t have anything about it. The information is missing.”

“Missing, how?” Jimmy asked. “And how could that be? Surely all computers have the same information?”

“All Earth computers do,” Vicki said. “Your phone is linked to the ordinary Earth internet, with the universal roaming system daddy put on it for you so you can access it on the other side of the galaxy and in a different century without a huge bill. But the information on theTARDIS database comes from a different source altogether, and Earl’s hand-held is linked to the TARDIS.”

“So the TARDIS database is wrong?” Jimmy concluded.

“No… not wrong… just giving a different version of what’s true,” Earl answered.

“So are those people dead or missing or perfectly alive and well if deluded?” Sukie asked. “I mean… we’re parked in the Omicron Psi quadrant in the twenty-eighth century, and they were in the nineteenth century, so they ARE dead, now, obviously. But are they dead in 1879?”

“Yes,” Jimmy answered. “Dead, or missing, at least. And I know about that kind of thing. I went through it all after my father disappeared. I only just got him formally declared dead. Those people died or were declared dead after a while. It’s on record. It’s a fact.”

“No,” Earl contradicted. “It never happened.”

“Well, one of you is right, and one of you is wrong,” Sukie suggested.

“It’s not ME,” Jimmy insisted. “Just because he’s a Time Lord and I’m just human….”

“You’re both right… and both wrong,” Vicki cut in before Jimmy started to feel patronised. “What this is… Jimmy, facts are not always facts. Not in the fourth dimension. I think… what the computers are telling us… is that it doesn’t HAVE to be that way. Because… we can stop it. We CAN change history so that Jimmy’s version and the TARDIS one match. We can stop those people dying.”

“Then stop talking and do it,” Jimmy said. “Those people are crackpots who follow the blathering of an even bigger crackpot, but they don’t deserve to die. Let’s get it done.”

Vicki and Sukie were already programming the TARDIS for the journey, slender fingers dancing across the keyboards. Earl watched them and then grasped a support. Jimmy took his cue.

“We’re crossing a reality boundary,” Vicki explained as she held the drive control lever down with a strength her petite frame hardly seemed to contain. “Between the history the TARDIS has on record and the one Jimmy found. She won’t like that. It will be a bumpy landing.”

Everyone held on tight as the TARDIS bucked and swayed and spun like a top. Vicki pressed her lips together and tried not to think about the rich dessert she had recently eaten. She didn’t want to see it come back the other way onto the console room floor.

When everything was finally still, the viewscreen showed a park with ornamental lighting that left large swathes of darkness beyond their reach. A gathering of people were creating movement in the shadows. The environmental console identified forty souls on that corner of Green Park.

“What are they expecting to see?” Jimmy asked impatiently as he wrenched open the door by the manual lever and rushed out. The others followed in time to hear him remonstrating with the nearest of the dark clad Victorian men and women.

“They are WAITING for a Chariot from Heaven to come down and bear them away to everlasting life in the Promised Land,” he said. “It’s crazy. That’s not going to happen.”

“What IS going to happen?” Vicki asked.

“Something BAD,” Sukie answered. “I… don’t usually get precognitive instances, but I’m having one now. They are NOT going to Heaven in a chariot. At least their bodies aren’t.”

Jimmy was still trying to persuade some of the people to come away. Earl did, too. He recognised some of them by face and name, members of the Learned Societies of Burlington House who had also been committed Southcottians. He tried to reason with them.

“Earl… Jimmy… come away, quickly!” Sukie cried out in terror. “Come away before it’s too late. Something is coming….”

She pointed up at the sky as the two young men responded to the fear in her voice. There was a bright light growing bigger as it came closer, resolving into a space ship of the ‘classic’ flying saucer style. The Southcottians were crying out in triumph and proclaiming the glory of God, oblivious of the danger.

“Please, just run away!” Jimmy begged one last time before he and Earl ran back towards the TARDIS. They both heard the unearthly sound but their backs were turned from the scene. They didn’t see the blinding beam of light that shone down from the ship and enveloped the crowd below.

They saw the horrified expressions on Sukie and Vicki’s faces and turned in time to see the Southcottians incinerated in the white hot inferno that scorched the grass. There was no mistake about it. They weren’t transported aboard. They were utterly destroyed.

All but one – Isaiah Westingholme himself, who ran from the beam and fell forwards. Sukie ran to him, and almost ran away again when she saw his back burnt through to the spine. She swallowed hard and knelt to give what comfort she could to the dying man.

“I thought…. they were… angels….” He whispered. “They promised… promised….”

With her hand on his forehead, doing her best to block the pain receptors in his brain, she saw what he was talking about. The beings had been silver-white and ethereal. They had used biblical verses to convince him that they came to him from Heaven. They had promised eternal life to him and his followers – just as Joanna Southcott had spoken of.

But they were nothing of the sort.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered to him. “I am so very sorry.”

“Sukie, we have to go,” Earl said to her. “The London Fire Brigade will be here, and the police. We really shouldn’t be here.”

“I know,” she answered. “I just wish….”

“I know. I’m sorry.”

He held her tightly as they walked back to the TARDIS. Inside, Jimmy was comforting Vicki who was crying openly.

“They… really are all dead, aren’t they?” Jimmy asked. “There’s no mistake… they weren’t transported aboard the ship?”

Earl held up his sonic screwdriver.

“I analysed the ash… there is human DNA in there. Not that the authorities in this time would know that.”

“Why?” Vicki managed to ask between sobs.

Earl didn’t know. It was Sukie who went to the environmental console and looked at the data.

“The TARDIS identified the ship. There are millions of space ships in the database. It recognised this one as a Tynarian harvester.”

“Harvester?”

“It… they… harvest….”

Sukie swallowed hard. It was hard reading.

“They harvest organic material…. People… they take everything in their bodies that can be used in some way. Their machines do that instantly, and then incinerate the… the waste… the pieces they can’t use.”

“And they came for the Southcottians?” Jimmy queried. “They tricked them into gathering on the green like that….”

“It…” Sukie shook her head. “It is horrible. I feel sick reading it. Apparently, they do it all the time. They can’t just murder indiscriminately. There is some sort of rule or law they actually stick to. They are only allowed to take willing sacrifices. So… they pose as mystical beings, promising eternal life, heaven, or just a lift to another world.”

“That’s not willing sacrifice,” Earl pointed out. “It’s trickery.”

“I know. But that’s what they do. It looks like they have targeted Earth a lot of times. There are tribes in places like the Amazon who have vanished overnight, forgotten until some archaeological expedition finds the ruined village. Then there are religious groups like the Southcottians who mysteriously disappear from amongst rational, civilised places like Victorian London. They’ve done it in all different time periods, too. They’ve got some kind of rudimentary time travel technology. This report I’m looking at is from the Shaddow Proclamation. They have been trying to put a stop to them for a long time. Apart from outright murder, they want to prosecute them for interference with this planet before it had official extra-terrestrial contact, impersonating local deities and unlicensed time travel.”

“The Shaddow Proclamation have funny priorities, sometimes,” Earl noted. “But going by the data on Jimmy’s phone, this lot have targeted the Southcottians regularly over about two hundred years. They’ve killed hundreds of them. The last were in 2014, the two hundredth anniversary of the first prophesised End Time in 1814. After that, I think people lost interest. There were no more attempts to gather, so no willing victims. If we dig deeper we might find a different pseudo-religious cult being targeted, but the Southcottians get a break after that.”

“We can’t stop them,” Vicki sighed dismally. “We tried… we were hopeless.”

“I don’t think we ever had a chance against technology that could turn us into fragments of DNA,” Jimmy pointed out. “The TARDIS has no weapons. We can’t shoot the ship down or anything.”

“We wouldn’t do that, anyway,” Vicki told him. “Daddy would never allow us, even if we wanted to. That’s not how Time Lords do things.”

“Then… I repeat… what can we do?”

“I think I know,” Sukie answered him. She had been quietly looking at the TARDIS database while everyone else was talking. She had seen something that offered a glimmer of hope. “Vicki… we’ve got another historical period to visit. It’s Empire waists and no corsets for us… high wasted trousers with dozens of buttons for the men.”

Clothes may have seemed a little trivial after the horror they had witnessed, but visiting historical times without the right clothes to blend in could be dangerous, especially when they were visiting people who were so firmly convinced that there were angels and demons ready to talk to ordinary mortals.

The year was 1813. The four time travellers came to a small boarding house in the Marylebone district of London where they asked to see Joanna. A certain amount of Power of Suggestion had to be employed, but they were, in a very short time, conveyed to the room where Mrs Sothcott was currently residing.

It was a good, clean room. The bed was made up with clean linen. There was water in a jug and a bowl of apples that were in season at the end of the summer.

Joanna sat by the window on a wooden chair padded with cushions. She looked much sadder than she had been in the portrait displayed in the Society of Antiquaries Library. There were care lines around her eyes and her hands shook as she reached out to greet her guests.

“My name is Sukie Campbell.” The young girl with a wisdom beyond her youth in her deep brown eyes took a simple wooden chair and sat beside her. “I… am a Healer. I make people well. I think you have been unwell for a little while, now, Joanna.”

The sad woman nodded and looked away towards the window, blinking away unexpected tears.

“I thought I was the bearer of a miracle… but it seems I was merely the vessel of a cruel trick. The demons used me.”

“Yes… they did,” Sukie confirmed. She grasped both of Joanna’s hands tightly and let her own mind touch the worried, tortured soul. She saw her memories of her first vision, the one that had made her write page upon page of prophecy and her long efforts to be taken seriously by the established church and the politicians she wanted to warn about impending disasters. There had been financial struggle and long periods of doubt, but also triumph as she began to gain followers.

But she was in a deep trough of depression and doubt, now. The phantom pregnancy, a medical condition that nobody in this era fully understood, would have been a disappointment for a woman hoping for an ordinary baby, let alone one expecting a new Messiah. She felt let down, and she felt she had let down those who believed in her.

Sukie was a little troubled. She had expected to find a charlatan who had misled her followers with a string of fake prophecies. She had expected to chastise her and make her recant her philosophies and release her devotees from any obligation they felt.

Instead she found a genuinely devout woman who had wanted to do right.

And that was much harder.

“Joanna, you are going to be all right,” Sukie promised. “Yes, you have been led astray by demons, false angels. But it is not too late. You must tell your followers that there is no new Messiah. You must also tell them that there is immediate apocalypse to prepare for. There are disasters to come, terrible wars, plagues, famine. Those things will be endured. You can help people endure them with your wonderfully inspirational writings. But… you must also tell them not to be taken in by the false angels. Tell them that there is no easy way to eternal life. No Chariot is going to bear them to Heaven. All they can do is live a good life and help each other along the way. Do you understand?”

Joanna was puzzled for a moment, then her tired eyes opened wide. She grasped Sukie’s hands tightly and nodded emphatically.

“Yes, yes, I understand. Oh, my dear Lord… I never expected His Messenger to come in such a form, but, yes, I understand. I will do as I am bidden. Young man…” she looked up at Earl who hovered close to Sukie in case she needed protecting. “Young man, will you help me up. My legs are weak these days. Let me go to the bureau over there and take up my pen. I have many new things to write down. New and wonderful things to tell to the faithful.”

Earl did so. At first as she stood, she did feel frail and unsteady, but before they reached the desk, she had begun to walk more confidently. There was the faintest of smiles on her face and even a twinkle in her eyes. She looked as if she had been given a new lease of life.

“I’m going to go down and have the lady of the house fix you some food,” Sukie said to her as she began dipping a pen into an inkwell and scribbling furiously. “Make sure you eat it. Your health is just as important as spreading the Word.”

“I will. Bless you, child. You have given me what none of the Messengers gave before… hope.”

With meat, bread and cheese delivered to the room there was nothing else Joanna needed. The four time travellers left her to her work.

“In truth, she was always a little bit mentally ill,” Sukie said when they were back in the TARDIS. “Her visions were the product of daily reading of the Bible mixed up with a fragmented consciousness. The phantom pregnancy was the same mental problems going up a few notches and affecting her physical body. After that… you know there was nothing really wrong with her. She died in 1813 mostly of depression and losing the will to live.”

“Not according to the database,” Earl contradicted. “She lived another ten years publishing and preaching about the way to Heaven through living a good life, telling people there were no easy ways to Heaven… no Chariots to carry them off.”

“My words,” Sukie noted. “Well, Isaiah Westingholme’s words. He talked about a Chariot.”

“The Southcottians carried on, but as a group who debunked End of World theories, promising that the world was not going to end as long as the human race looked after it. Isaiah was one of the most vocal of his age. His great-great-great grandson was even more so in the second half of the twentieth century, warning against nuclear proliferation.”

“He didn’t die in 1879?” Vicki asked.

“No,” Jimmy answered her. He held up his phone. “My history matches up, now. We’ve made it right.”

“I suppose the Tynarians will still try to trick people,” Sukie considered. “But not using Joanna’s teachings, and not fooling any of her followers. And I made her happier than she was. We did a good thing. And we didn’t even REALLY break any of the laws of time. The window was there… the TARDIS database showed us that we could do it.”

“There’s just one thing I’m REALLY curious about,” Earl said. “I wonder….”

None of the four were Associates of the British Museum, but as it happened, Vicki’s father, The Doctor, WAS. He had, he claimed, been a patron since it was founded in 1753. He was still a patron several hundred years on and nobody questioned his credentials. The staff were happy to indulge him with a private viewing of an artefact.

“That’s the box everyone made such a fuss about?” Jimmy asked as they looked at the old but sturdy portable bureau placed on a table in the archive office. There were, by coincidence, twenty-four chairs around the table, but there were no bishops.

The box looked so plain, so ordinary, it was hard to believe that it had seemed so important to so many people.

“That’s Joanna Southcott’s Box,” Earl confirmed. The underlying joke had ceased to be funny. Nobody smirked. Nobody elbowed anybody.

The Doctor adjusted his sonic screwdriver and aimed it at the box. Very slowly the contents materialised outside. It was a collection of loose pages, preserved perfectly in the sealed container.

“They ARE predictions of the future,” Vicki said. “Joanna’s future. Wars, earthquakes, all sort of things. Even…”

She held up a sheet with a small ink drawing on it. The shape was familiar to all.

“Joanna predicted the Daleks invasion?”

“That might have been my fault,” Sukie admitted. “Joanna probably was a little bit psychic, and when I was reading her mind, she might have seen a bit of mine. I had been thinking about the Dalek war.”

“Possible,” The Doctor said. “It’s also possible that she was a genuine prophetess. It happens, sometimes, even among the human race. There is, I’m afraid, nothing in her writing that could have prevented the Dalek invasion or any other disaster. Even if there had been, the inability of humans to listen to reason would have made her warning futile.”

“There’s a lot more stuff here,” Jimmy pointed out. “Do you think some of it hasn’t happened, yet?”

“That’s quite possible, too,” The Doctor added. He put his hand over the pile of papers. “I’ve ALWAYS said that it’s dangerous to know too much about the future – your own future or the future in general. I’m not saying you can’t look. If you really want to, go ahead. You’re all of you old enough and smart enough to decide for yourself whether you want to accept the burden and the responsibility.”

The four of them looked at The Doctor, then at each other. Jimmy couldn’t tell what the others were thinking, but he didn’t really need to.

“Joanna Southcott had the burden for all those years and it made her miserable,” he said. “I vote for putting this stuff back and forgetting about it.”

The others nodded in agreement. The Doctor reversed the process, sending the papers back into the box. There was a soft, collective sigh around the table. They all knew they had made the right decision.

“All right,” The Doctor said. “Let’s get out of here before we outstay our welcome, or somebody realises that my credentials are over four hundred years old.”

|

|

|