The drawing room of Mount Lœng House was a male only preserve for once. Rose was starting a cold and had gone to bed with a lemsip and a box of moist tissues. Jackie had gone to bed, too. She was already at that stage of her pregnancy where she got tired very quickly. Which for a Human carrying a Gallifreyan baby was most of the time. The Doctor, Christopher, David and his sons were having a drink together. It was the sort of scene that the Georgian drawing room was always meant for.

“Do you gentleman require anything else tonight, sir?” Michael Grahams asked dutifully as he stepped into the drawing room.

“The pleasure of your company, Michael,” The Doctor answered. “Come on, sit and have a drink. Your wife is away isn’t she?”

“Yes, sir,” Michael said as he tentatively moved towards an empty seat. “She is visiting her sister.”

“There you are then.” The Doctor stood and went to the drinks cabinet. “What would you like.”

“Whiskey, if you please, sir,” he answered.

“You’re off duty, Michael,” The Doctor told him as he poured his drink. “You don’t have to call me sir. In fact you don’t really have to call me sir even when you ARE on duty.”

“Thank you, sir,” Michael said as he took the drink. “Sorry, sir. I mean to say….”

“My friends call me Doctor,” The Doctor said. “I know that’s an odd kind of a name. It's such an old story that even I have forgotten it. But it’s the name I go by.”

“Doctor…. A name that has legends written alongside it.”

“Not all of them true,” he admitted.

“It is true that you are the one who defeated the Daleks,” Michael said.

“Not entirely true. I did my bit. But it was ordinary Humans like David who never gave up the fight for freedom who really did it.”

“He always says that,” David contradicted him. “We were going under slowly when he arrived. The Doctor and Susan, with Ian and Barbara.”

Christopher sat up attentively. So did Chris and Davie. For very similar reasons The Doctor’s son and his great grandsons wanted to hear more of this, the story of the defeat of the Daleks. It was in the midst of the fight that Susan had fallen in love with David and set all their fates in motion.

“That story has been told so often,” The Doctor said. “What I don’t know much about is what happened to you all after I left. What was it like putting the world back to normal?”

“I didn’t have a lot to do with it,” Michael admitted. “I was only six when my parents died….”

“In the war?” David asked.

“Yes,” he answered. “They were in the resistance. We all lived in the basement of a big house in North London. About twelve families. All our parents fought while we children hid. Sometimes parents didn’t come back. One night, it was my turn. I never really knew what happened. Nobody really talked about it. The way Daleks killed people… I always imagined it must be very dreadful….”

“It is,” The Doctor admitted. “There’s no sugar coating it, Michael. If your parents fell victim to the Daleks in open battle…. Well, their way of killing is complete. It ALWAYS kills. That is the only mercy about it. It’s quick and final. They leave no maimed and broken people. Only dead ones.”

“That’s what I came to understand later. From those who would talk about it at all.” He took a gulp from his drink. “It was only about a week before the end. They were among the last victims. They ALMOST made it.”

“Oh.” The Doctor’s expression then was one of anguish. A week. If they had arrived under that bridge on the embankment a week earlier, would Michael’s parents have survived?

He felt guilty. For all of those he had not been able to help. For Michael.

“Granddadd,” Chris told him. “Don’t think like that. It wasn’t your fault.”

“Certainly it wasn’t,” David insisted. “In a way… it wasn’t even your fight. You didn’t even HAVE to help. You have nothing to be ashamed of.”

“Granddad,” Chris spoke to him this time telepathically. “Don’t think that, either. The Time Lords were WRONG to ask you to go back and commit genocide against the Daleks. Even knowing what they did to Michael’s parents, and to so many other people, and knowing what they did to you since, it was still wrong. And FAILING that time WAS the right thing to do. Besides, if you had destroyed them, if Earth hadn’t been invaded, then mum and dad wouldn’t have met. We wouldn’t have been born.

That was a very small consolation for the holocaust the Daleks wrought upon the universe. But Chris was right. In the bigger picture, he had always been doomed to fail in that attempt because it would have unravelled the universe if he had succeeded.

But when you came in from the big picture and saw it in terms of a six year old boy whose brave parents went out one night never to return, it was much harder to be philosophical.

He certainly didn’t want to have to explain to Michael that his parents died because half a million years before HE had baulked at putting two wires together.

“So… you would have been one of the orphans that the provisional government’s first Act provided for?” David asked Michael.

“Yes,” he said. “All the homeless and orphaned children of London were brought to the Palace – Buckingham Palace. It became an orphanage. The government.... that first Act was a financial settlement for all of us. To provide shelter, clothes, education for us so that we would have a stake in the future the adults were building. We were the children of the lost generation.”

“You were a bloody nuisance half the time,” David said as he remembered. “The adults were doing their best to get the infrastructure back, the railways and roads, broadcasting, get hospitals functioning, schools… and the kids ran wild, fighting and stealing and undoing all the hard work.”

“Michael!” Christopher said with a wry smile. “Is that true? I don’t recall any juvenile delinquency on your CV when father and I interviewed you for the post here!”

Michael laughed softly.

“The worst my crowd did was scuff all those antique floors of the Palace with our shoes. I wasn’t even one of the smokers. I won’t say there wasn’t some shoplifting for cigarettes and sweets, that sort of thing. That’s when there WERE shops and cigarettes. I was nearly sixteen before people were able to take things like that for granted again.”

“That’s true enough,” David admitted. “Most of it was just petty badness. Still, it did seem sometimes as if the children of the lost generation weren’t going to make it.”

“We made it,” Michael said. “Some of us did well enough. One of my best friends in the orphanage… Larry Bell… he did very well.”

“Lawrence Bell?” Christopher looked up in surprise. “Member for Kilburn?”

“That’s him,” Michael answered.

“A shrewd politician,” Christopher observed. “Very shrewd. Likeable man. And yet... what’s that Earth expression. Wouldn’t trust him as far as I could throw him.”

Michael laughed. “That’s Larry. You’re a good judge of character, sir.”

“Please just call me Christopher,” he reminded him. “But Larry was here a couple of weeks ago when we had a dinner party…”

“That was the night you said you had a bad stomach and asked to be excused,” The Doctor noted. “Michael….”

“I like my job. The butler training school… when I finished school, I was never going to be an academic, and I wasn’t much of an engineer. But in the new Britain that had come into being while I was growing up there were already people who could afford to hire others to work for them. And I found satisfaction in being of service… but when I heard he was coming here… I wasn’t exactly ashamed to be merely a butler but…”

“Next time we have a dinner party,” Christopher said. “You are my guest, Michael, you can tell everyone you’re the head of New Scotland Yard, if you please. Except if Dennis Glover is at the party. He IS head of New Scotland Yard.”

“I think the truth is usually better,” Michael said. “But thank you for the offer.” He went quiet for a while and even David, the only other non-telepath in the room, knew he was thinking about the friends of his youth.

“There were two others in our gang,” he said presently. “But they didn’t make it. Danny was killed and Patrick disappeared. Nobody ever worked out what happened in either case. The police… Ten years on, they still had rooms full of missing persons reports from the war. Patrick was another page in the file. And Danny… Danny… well he had problems. There’s no doubt about it. He wasn’t a happy boy. But I couldn’t understand why anyone would kill him. And nobody really made much effort to find out. Again, the police had plenty to do without worrying about an orphan boy that nobody was grieving for except the other orphans who knew him.”

“That’s sad,” Davie commented.

“Somebody should have cared,” Chris said.

“Yes,” Michael said. He smiled at the grandsons of his employer. He could so often see in them something of the spirit he and his friends had when they were boys. But they had been born long after the war, and born into a family where love was never in short supply.

The lucky ones.

“Sir…” he said after a long pause in which Christopher stood up and poured a fresh round of drinks. “I mean… Doctor… Your machine… the one in the basement. It can take you to any point in time? That is how you came to London in the midst of the war?”

“It is,” The Doctor answered. “Although at the time I wasn’t entirely in control of it. There were problems. It brought me and my companions to random locations. It was pure coincidence that we were there to meet with David and his resistance cell and became involved in the fight.”

“But now… you could go anywhere.”

“Yes.” The Doctor didn’t need much precognition to work out what was coming next. “Michael, understand one thing. What is done is done. I can’t change it. Time travel can’t be used to change what has already happened.”

“Sir…” Michael looked slightly embarrassed at appearing so transparent. “I would not dare to ask you to do such a thing for me.”

“Michael.” The Doctor looked at him steadily. “I often wondered if your deferent nature is natural to you, or do they teach it you at butler school? Either way… please ASK. The worst I can say is no.”

“I understand that Danny is dead. He has been for a generation. But I would like to know who did it, and WHY. Because I never believed what everyone was ready to believe…”

“That he was killed by your other friend, the one who disappeared….”

Michael nodded. The Doctor looked at his watch. It was ten thirty. He promised Rose he would be in bed by midnight.

But he had a time machine, after all.

“Anyone who wants to come for a quick trip, get your coats. I’m just going to tell Rose I’m going out for a bit. You know how she likes to be told these things.”

When he returned the only one who HADN’T put his coat on was Christopher.

“I don’t really want to leave Jackie. And somebody needs to be here for the children, with Rose not feeling so well. Besides, I’m not sure I could look Lawrence Bell in the eye again if I was to meet him as a teenage petty thief.”

“All right,” The Doctor said. “See you later. Everyone else… to the basement.”

Michael had travelled in the TARDIS before. The Doctor had included him several times in trips to their favourite restaurant. He had accepted the technology as he accepted the fact that his employer was an alien exile on Earth.

With an amazing capacity not to worry about what he didn’t understand.

“It is a remarkable ship,” he said to The Doctor as he watched him work at the console. “Your own people must have been very powerful.”

“Not so powerful as we thought. The Daleks wrought their havoc upon us. We were lost. More lost even than Earth.”

“I am sorry for that, sir. If you are an example, they must have been fine people.”

The Doctor looked at him, then turned away. He blinked back a tear. The first he had shed for Gallifrey in a long time. The raw wound he thought never would heal had begun to stab at his soul much less since he settled on Earth and began to look to the future of his people. The birth of his children, the twins transcending, the discovery of the ‘Israelites’ and their resettlement on Earth, had all given him a focus.

But just now, the pain hit him as hard as it ever did. He mourned anew for all that was lost.

“I feel the same way.” He looked up and saw David standing near him.

“How do you know how I feel, David?” he asked. “You’re not telepathic.”

“Who needs telepathy? I can see you burning up with the fury, the pain of remembering. It’s the same for me. For all of the survivors. Most of us have looked forward, kept focussed on the future, on building and rebuilding. But sometimes, we’re forced to look back, forced to remember the past. And it all comes back, all the hurt, all the pain.”

“You never seemed to be in pain,” The Doctor told him. “When you were fighting. You were strong. You never despaired, never gave up. I admired you. Even if I didn’t say so.”

“Humans are good at hiding their pain. Especially when we have no time for it. There was no time for tears while we were fighting. It was afterwards that it hit us. When we looked about us at our destroyed world. For me… You never asked why we came back to London. When you left us, Susan and I were going to go to Scotland to work on my parents farm…”

“Yes,” The Doctor said. “I remember that. I remember thinking that Susan would look good milking cows.”

“There were no cows. There was no farm. No village. They had resisted. Everyone did.” He laughed ironically. “Scots tenacity, I suppose it was. Our ancestors fought the Romans, the Vikings, the British. We fought the Daleks. But the Daleks retaliated. Scorched Earth… they wiped out the townland. People, livestock, crops… all burnt. My parents… I had no idea. No idea how or when they died. Only that they WERE dead.”

“David…” The Doctor reached and put a hand on his shoulder. There was no need for words. There were few words he could say. Comforting platitudes were meaningless to both of them. They both knew there was no comfort, nothing that eased those memories for either of them.

“Doctor,” David said after a long pause. “Before, when you fought the Daleks with us, it was because you knew their evil. You’d seen them before, and knew them for what they were. But it wasn’t personal. They hadn’t hurt you. But now… Forgive me for the thought that has so often crossed my mind.”

“You feel as if my planet being destroyed made us equals, you and I. And then you realise that the idea pleases you – that levelling, that bringing me down from my high place to be just another of the walking wounded. And then you censure yourself for taking pleasure from the deaths of so many people.”

“Something like that,” David admitted. “Sorry, Doctor. It is a TERRIBLE thing to think about anybody.”

“But it’s the truth. I was always just a clever meddler in other people’s affairs until it came home to me with a vengeance. There’s nothing to apologise for. Sometimes I do wonder myself, if what happened to us… We deserved it in many ways. For our arrogance. It was our wake up call and we were caught napping.” He sighed and then smiled. “David, yes, we are equals now. Equals in remembering a terrible past and in the stake we have in the future.”

They both turned and looked at the twins, working together confidently and competently, gathering data about the time period they were heading towards. David smiled at them both. He fully understood what The Doctor was saying.

“They’re the one compensation both of us have. Our children. Our future.”

“We’re lucky,” The Doctor agreed before he turned his attention to their materialisation in post-invasion London.

“Hyde Park?” Chris queried as they stepped out. It WAS definitely the place he knew. But it was overgrown and derelict now. The grass was full of weeds and had been cut only roughly. The memorials and statues were all full of verdigris and most of them were damaged.

“It’s where we used to go,” Michael said. “All the kids. We would play games, fight, that sort of thing.”

When he said ‘games’ everyone thought of football or cricket or rounders, or something of that sort.

They all felt rather shaken by the game the childen WERE playing.

These weren’t Michael’s group. They were too young. Only about eight or nine years of age. Perhaps that was why they COULD play such a game.

“Look,” one of the children said to the others. “Albert Memorial is the Dalek leader’s ship. We have to fire our artillery at it. But you have to be careful because Paul and Martin and Jem are Robomen guarding it and they can call the Daleks.”

“Who are the Daleks?” the boy asked, wiping his nose on his sleeve and clutching a stick that was his ‘gun’.

“Gary and Mark and Brian,” the first one answered.

“I don’t want to be a Dalek. I want to be a Human who kills Daleks.”

The protester was Brian. A squabble ensued and the ranks of protagonists were reorganised before the assault on the Albert Memorial began in earnest. Judging by the amount of rocks and rubble around the base and the mud that spattered it, even as high as the head of Prince Albert, it was not the first such assault.

“They can’t even know what a Dalek LOOKS like,” The Doctor said. “They were born after…”

“They’re in the history books at school, Davie told them. “We learnt about them there. Before we found out that our DAD was a hero of the war, and that our GRANDDAD was their arch-nemesis, Ka Faraq Gatri, the Oncoming Storm.”

The Doctor half smiled at those epithets earned in his lifetime of struggle against the Daleks. They never underestimated him any more than he underestimated THEM.

“We never thought of it as personal,” Chris said. “We thought of it as something that had happened once.”

“There are no history books with them in yet,” David said. “That came a bit later when people realised they had to tell the next generation what happened, so they wouldn’t forget, wouldn’t take their freedom for granted.”

“Hah!” his elder son retorted. “Our geography teacher used to tell us it was all a hoax. That it was just a mass hallucination brought on by the virus that killed so many people.”

“Your geography teacher was never in Lanark,” David responded. “A virus didn’t do THAT.”

Davie almost began to ask his father WHAT was done in Lanarkshire then changed his mind. Although his father never lost his Scottish accent, and his pride in that heritage, he had never once, in all their years, taken them to visit Scotland, and Davie thought, just then, he had a glimpse of why.

“This wasn’t a great idea, you know,” Chris said to him telepathically. “Coming back. For them… they’re all hurting. Dad, Granddad, and Michael.”

“They’re not the only ones.” Davie touched his brother on the arm. He looked around as a group of older boys approached. Four of them, all about sixteen or seventeen. They were dressed in jeans and t-shirts of a universal and timeless sort, but all of them wore a sort of scarf around their necks with a crest on it, as if they belonged to the same school or some other institution. They were all watching the game the boys played with expressions of disgust and horror.

All but one. He stepped towards the boys. He looked horrified but at the same time fascinated.

“That’s not how you kill Daleks,” he shouted. The younger boys all looked at him as he strode through their ranks. When he was within a few feet of the Albert memorial he reached into his jacket and pulled out a gun. A REAL gun. The youngsters screamed and ran as he began to fire. “DIE, you…. You… murdering metal scum… you slime… you murderers…” He was crying as he fired blindly, chipping lumps off the heroic frieze at the base of the statue.

“Danny, come on!” One of the other boys stepped forward. Michael gave a soft gasp and they all knew it was his younger self who was going towards the boy with the gun. He made to step forward but The Doctor put a restraining hand on him.

“Michael, YOU can’t get involved. You mustn’t touch your younger self, not even for a moment. It creates a paradox. Your molecules and his can’t connect.”

“They’re going to hurt each other,” Michael said. “This fight. They’re best friends, but there was so much bitterness.”

“I know. But you mustn’t.”

“Leave me alone,” Danny responded as the young Michael tried to restrain him. The other two boys hovered uncertainly, not sure whether to intervene or not.

“My parents died too,” Michael said. “So did Patrick’s and Larry’s. We all suffered the same.”

“None of you SAW it happen,” Danny responded. “You didn’t SEE it. They killed them, and left them lying in the street. I ran to them. Their eyes were open. I thought at first they were all right… but their eyes were dead…” He fired again into the frieze and then turned on his friend, the gun turned, holding the barrel and hitting out with the butt. “Don’t tell me not to remember. Don’t tell me not to… not to hurt. That damned psychiatrist, telling me I have to move on, have to HEAL. I CAN’T heal. I can’t turn back the clock and make it not happen. I CAN’T HEAL.”

Michael yelped as he took the butt of the gun in his face. The older Michael looked pleadingly at The Doctor.

“You said we can’t turn back the clock, either…”

“No, we can’t.” The Doctor said. “For any of you. I’m sorry.”

Danny was still hammering Michael with the butt of his gun. Michael was fighting back as they fell to the ground and grappled each other.

“Stop!” Chris called suddenly, and he ran towards them. “They’ll kill each other. If you’re their friends, stop them.”

Chris’s voice stirred the other two out of their shocked inaction. Between the three of them they separated the fighting boys. Danny jumped to his feet and ran off. David and Michael looked at each other and ran after him. The Doctor and Davie both joined the rest of the boys. The Doctor went to the young Michael who was fainting in the arms of his two friends.

“Set him down gently,” he said, taking out his sonic screwdriver and setting it to tissue repair. “That’s a serious concussion. Look at me, lad. How many fingers. Come on, focus.”

Michael managed to focus, but he saw twice as many fingers and his voice was slurred as he spoke. The Doctor applied the tissue repair mode to the skull injury that gave him the most concern. The other boys looked on in surprise.

“It’s ok,” Chris assured them. “He’s The Doctor. He’ll look after your friend.”

“You’re a Doctor?” The one who had to be Larry laughed. “You look like a road-worker. That jacket is RUBBISH. I know where I can get one. Bloke I know, works in exports and imports. Real leather, for a hundred euros.”

“Larry,” The Doctor replied without looking up at him. “There is a time and a place for trying to peddle hot leather goods. This isn’t it. Michael, close your eyes while I do your cheek. The light isn’t dangerous but it can make you feel queasy looking at it for too long.” He applied the analysis mode to the cheekbone first and detected a hairline fracture. The repair mode dealt with that quickly and easily and took away the ugly bruise across his whole cheek.

“That’s the worst of them dealt with,” The Doctor said after a while. “The rest of the bruises you’ll have to deal with like any teenager does. But at least you don’t need hospitalising.”

Michael put his hand to his head. There was blood there, but the wound was gone.

“How did you do that?” he asked. “It doesn’t hurt at all now.”

“Just part of the service,” he said. “Try to forgive Danny. He wasn’t thinking straight.”

“Danny never is,” the one called Larry said. “He’s cracked. He sees a psychiatrist every week. He’s been like that since he was a kid.”

“He really did see his parents die?” The Doctor asked as he stood, lifting young Michael to his feet.

“Yes, he did,” Patrick, the quietest of the four, told him. The Doctor noticed him clutch what looked like an old fashioned transistor radio close to his chest as he spoke. A comfort object? Something that had belonged to his family? “Michael and I share a room with him. He has nightmares about it all the time. Even all these years on.”

“I can relate to that. I have nightmares about the Daleks, too,” The Doctor said.

“You fought in the war, sir?” Young Michael asked. “Did you… did you lose people?”

“I lost everyone,” The Doctor answered. “I know what Danny is feeling. I am sorry after all this time he hasn’t started to cope with it. But I know what he feels. Do you know where he might have gone?”

“The memorial,” Larry said. “He goes there a lot.”

“Memorial?” The Doctor asked. “Show me.”

When he saw it, of course, he knew the memorial they meant. He knew it from the 21st century when he first met Rose in London, and he knew what it looked like in another forty years or so from now, after he came back to London.

This was the Holocaust Memorial Garden, from the late 20th century, commemorating those who died at the hands of a Human force The Doctor counted alongside the Daleks for evil intent. It had been a simple monument to begin with, a stark contrast to the over-elaborate Albert Memorial. Here, two boulders had simply been set in a small garden of flowering plants and shrubs, one of them bearing a suitable inscription. After the invasion, memorials, like parks, were not at the forefront of the official plans to rebuild the Human race and its infrastructure, but the people had made their own memorial. Several more large boulders were put into place and names of the dead were carved or written on them. These large boulders were supplemented by smaller rocks and stones placed around them, each representing a victim of the Dalek war. At some future point the authorities would get around to setting all the smaller stones into concrete for posterity, but for now they were loosely gathered.

Danny was sitting on the ground by the memorial, crying piteously. David and the older Michael were trying to comfort him, but he was not being comforted. He clutched two fist sized stones from the pile and cried.

“Stay back,” he whispered to everyone else. “Especially you, Michael,” he added. “I’ve patched you up once already.” He stepped forward. Danny looked at him with suspicion in his eyes. Another person come to tell him it was all right and he should get over it.

“You never get over it,” The Doctor said. “Don’t let anyone tell you that. But most of us find a way of living with the bad memories. For me, it was my children. But you’re too young to have that kind of comfort, Danny. What can we do to restore your belief in the future?”

“Nothing,” he replied. “Nothing. Just leave me alone, mister. I don’t need anyone messing with my head.”

“I think maybe you do,” The Doctor told him. He reached and touched his forehead and gently calmed the mess of grief in the boy’s head. He calmed enough for The Doctor to lift him to his feet. He dropped the two stones. They rolled against the pile of other stones.

“Do you want to give me the gun,” The Doctor said quietly. “It’s not a good thing for a boy to be running about with.”

Slowly Danny put his hand in his pocket. For a heart stopping moment he held onto it, as if he might start shooting again any moment. Then he passed The Doctor the gun. It was an automatic pistol and from the weight of it there was at least half the magazine left. He put it in his jacket pocket without a word.

“You boys take Danny home now,” he said. “It's nearly lunchtime anyway.”

“You’re not going to arrest him for having a gun?” Larry asked. “You’re a copper aren’t you?”

“No, I’m The Doctor. And before you reckoned I was a road-worker. What makes you think I’m a copper now?”

“You sound like you’re in charge. But you’re wearing that scruffy jacket. You’ve got to be a copper. Nobody else your age would dress so uncool.”

“I’m not a copper. Lucky for you, Larry, seeing as I know about your dodgy leather goods retail operation. Go on now, the lot of you.”

It was young Michael, who had suffered most from Danny’s outburst of pent up anger and grief, who came to him first, taking him by the shoulders. The boys all walked away in the direction of The Mall.

“I thought you couldn’t change anything,” David said to The Doctor. “You took his gun…”

“I didn’t change anything,” The Doctor answered. “He was KILLED. It wasn’t suicide. He’s still going to die. The gun is nothing to do with it. I took it from him because 16 year old boys shouldn’t have things like that. But….” He looked at Michael. “It’s tonight, isn’t it? When I touched him I felt it strongly. I could feel his lifeline. And it cuts off in a few hours.”

“Some things changed,” he said. “I didn’t spend the night in hospital, because a man came along and fixed me up. I have you to thank for that much, Doctor. But I still can’t stop Danny from dying?”

“None of us can do anything to stop that happening,” The Doctor told him. “And we mustn’t try. I don’t know. Maybe coming here wasn’t such a good idea. It’s opened old wounds in all of us. Michael… We could call it off now, go home. Or we can stay… purely to find out what happened and why. Which means we don’t intervene no matter how heartbreaking the situation is. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, I do. When I asked you to do this… I just wanted to know what happened. That’s all. That’s the whole thing. Just who and why.”

“All right then,” The Doctor agreed.

At the back of his mind he had more than a bad feeling about this. He had a horrible sense of déjà vu.

He should have said no. He should have known better. It was just like when Rose asked him to take her back to the day her dad died. In the moment, she hadn’t been able to stop herself jumping in there and doing something. And it had nearly been the undoing of them all.

And how could he stop Michael, if it came to the crunch, from trying to stop his friend from dying at 16 years of age? He had wanted to do it himself. For a moment when he took the gun from him he DID think he had done it. But the timeline still cut off after that. When he had touched his hand afterwards he could still feel the terrible dead end to his life within a few hours.

And yet, it could work sometimes. When they played Ghost of Christmas Past to Brian Gill, he had amended his ways and avoided being murdered by Spanish criminals. The reason that didn’t bring on an attack of the Reapers was that it was Brian himself who effected the change.

Maybe…

“Doctor,” David called to him, shaking him from his reverie. “There is one small thing you could do. With your sonic screwdriver.”

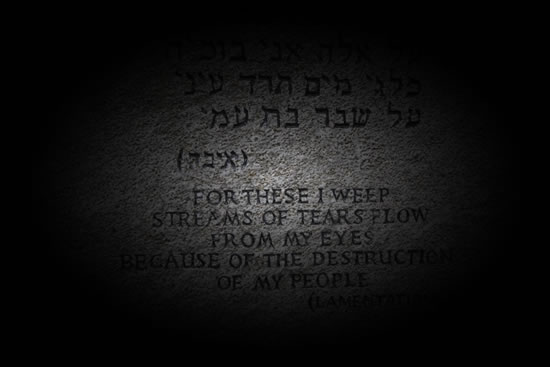

He looked down and saw David kneeling by the main memorial boulder. The one that had been placed there in 1983, a little less than 200 years before this date in 2174. The inscription was faded now. It had obviously been renewed from time to time over the 200 years, but it had been forgotten for a decade.

Underneath it, somebody had tried to inscribe something else, faintly scratched with a knife or some such thing.

The Doctor nodded and knelt beside David. He adjusted the sonic screwdriver to the powerful laser cutting mode and applied it to the rock, his hand steady as he carved words taken from the Book of Lamentations in the Earth Bible that might have been written for his own people and his own grief.

“For these I weep. Streams of tears flow from my eyes because of the destruction of my people”

And beneath it he set the new inscription into posterity. It was also from the Earth Bible. The Doctor knew as a matter of literary fact, that it came from the Second Book of Kings.

“I have heard your prayer; I have seen your tears. Behold, I will heal you.”

“That’s what this planet needs now,” David agreed. “Healing. Danny, and all of us.”

Healing for Danny was going to have to be very fast, he thought. But if he died at peace with himself, instead of the tortured soul he appeared to be, then it was something.

“Was Danny always like that?” David asked Michael as they walked through the neglected Park.

“Not all the time,” Michael admitted. “Yes, he did have the nightmares. Patrick was good to him when it happened. He used to be able to calm him down. But most of the time he could be perfectly normal, as happy as any of us were. Then every so often something would trigger it. Just as you saw today. And he would react violently, even towards his friends.”

“Poor kid,” Davie said. “The Daleks did that to him.”

“They did a lot to all of us,” David answered his son. They both looked at The Doctor, who wasn’t looking at anyone right now.

If there was a victim who had suffered more than Danny, it was him. The people who thought they understood about post-traumatic therapy would have to write a whole new book just for him.

“When did it happen?” The Doctor asked. “And where? Danny’s death, I mean.”

“It was over there, by the Albert Hall, some time after dark. Nobody was entirely sure. They didn’t find his body until morning. He and Patrick were missing from their beds and it was only at breakfast that anyone knew. The police found Danny’s body but there was no sign of Patrick. He vanished off the face of the Earth.” Michael paused. “At least, that’s what I heard, of course. I was in hospital that night, because of Danny’s outburst. We didn’t tell anyone it was Danny, of course. We didn’t want to get him into trouble. We blamed it on a rival gang ambushing us. I sometimes wonder… if we HAD told the truth, they’d have put him in the sick bay under sedation. He wouldn’t have gone out with Patrick…”

“But you didn’t. And that can’t be changed,” The Doctor told him. “So don’t beat yourself up about it. Let’s find somewhere to eat while we’re waiting for it to get dark.

Lights out in the orphanage was nine-thirty for the senior boys. The younger ones were already settled. Danny made a pretence of taking his sleeping pill under supervision of the house-master but as soon as he left the room he spat it out into the waste paper bin. He didn’t want to sleep. Even the pills didn’t stop the nightmares and he knew that tonight was going to be one of those nights when he had the nightmares.

He drifted off to sleep for a little while. But something woke him. A noise. He turned over in his bed and saw Patrick heading for the door. Nothing unusual there. He was just going to the toilet, he thought. But why did he take his radio with him? Usually at night he was content to have it under his pillow. The radio that had never worked. Didn’t even have batteries. But his father, Patrick said, had given it to him and told him not to lose it, before he had fallen victim to the Daleks.

Danny got up out of bed quietly and went through to the common room they shared with all the other boys on this landing. Patrick was sitting at a table in the corner of the room. The radio was in front of him. And it was working. A blue light lit up the waveband window and there was a voice coming from the speaker.

A voice speaking a foreign… no, an alien language.

And Patrick was responding in the same language.

Danny watched in silence, from the shadows. The conversation went on for a long time. Patrick seemed very emotional and very excited. When it was over, he stood and headed for the landing door.

Danny followed. He was in his pyjamas, dressing gown and slippers, but so was Patrick. He would hardly outpace him.

A few yards behind, Michael followed them both, wondering why both of his friends were acting oddly.

When this was a Royal palace, of course, there was security all over it. But now it was an orphanage, and once the children were in bed the staff considered their work done. Nobody thought it necessary to check beds. These were children who worked hard and played hard and they were tired enough to sleep when they went to bed.

The doors were locked for their own safety. But locked from the inside, and the keys were on long chains in case of fire. Patrick easily opened a side door and slipped out into the courtyard. Danny easily followed him.

Again, in the old days, this was a place where soldiers were always on guard, and should they fail, there were security cameras. None of those things were needed for orphan children.

The side fence was easy enough to climb. All three, in turn, scaled it. Michael, coming up in the rear, got his bearings and knew they were heading towards Hyde Park, and as they got closer, he realised they were coming to the Albert Hall.

The roof of the Hall had been destroyed by the Daleks. They seemed, Michael always thought, to have chosen to ruin such things purely out of spite. Things that meant something to Humans were spoilt, but not completely destroyed. Leaving it there, as a ruin, was a way of reminding them of their subjugation.

It was still derelict now. There were debates in the government about whether to repair it or demolish it. Meanwhile the finery inside had disintegrated over the years, and it was a playground for the local children. The authorities boarded it up, saying that the floors and stairways and galleries were dangerous, but since when had that ever mattered to children? They found a way in, anyway.

Patrick found a way in where the boards across the main entrance were loose. Danny followed him. Michael followed them both. Slippered feet made little or no noise in the dark interior passageways that led to the main auditorium. Michael saw Patrick go right out into the centre of the big, round central arena as Danny hid in what remained of the stall seats and watched him carefully.

For a long while, nothing happened. Patrick just stood there, looking up at the ragged circle of starlit sky above him. Danny watched Patrick. Michael, in the shadows alternatively looked up to see what Patrick was waiting for and watched his two friends.

Then something happened that he was sure Danny wasn’t expecting, but Patrick clearly was. A light that he had thought was just another of the stars got bigger as if it was coming nearer. At first he thought it was a helicopter. The police used them to patrol the streets at night. But there was no noise. And as it came closer he could see that it was an elongated oval shape, completely unlike a helicopter.

He knew what it was, of course. A spaceship. He remembered them well enough, from his childhood. The Daleks had ships that were like great upturned soup plates with lights all around them. In old comic books from before the invasion, science fiction writers had been amazingly prophetic in their drawings of what alien craft looked like. Michael remembered seeing some of the old pictures in a museum and finding them so chilling as he remembered the fear the real thing caused deep in his soul. He felt that fear now, even though this ship wasn’t quite the same. It WAS alien.

Yet Patrick didn’t seem afraid of it at all. He seemed to be eagerly expecting it. As the ship settled over the gap in the roof of the hall he raised his hand in welcome to it.

Michael watched as a beam of light came down from the ship and a figure materialised in it. It looked humanlike, with one head, body, arms and legs, but it wasn’t Human. The man who stepped towards Patrick had flesh that looked like that of a marine mammal like a whale or dolphin except green and burnt-orange coloured. He was completely hairless and wore some kind of skintight suit in the same colours as his own skin with a silver belt at his waist.

“Patrick! Get away from there!” Danny screamed, breaking cover. “It’s an alien. A scummy, murdering alien. Get away. Before it kills you…”

Patrick looked around, startled. His alien companion was even more astonished.

“Danny, you shouldn’t be here,” Patrick said. “Go back to the palace. This is nothing to do with you.”

“What are you doing?” Danny asked. “Why are you with that… that filth?”

“Because… Danny… I’m sorry, you weren’t meant to see this. You shouldn’t have followed me. But it’s time for me to go home. They lost us a long time ago. My family. We were here on Earth when the Daleks struck. We were trapped. My parents… they helped with the resistance. It wasn’t their planet, but they knew evil when they saw it. they did their bit. My father gave me the transmitter. He told me our people would come eventually. It might take a long time, but they would come. I had almost given up hope, but tonight… I got a signal. They were in range. They were coming for me.”

“You’re ONE OF THEM!” Danny screamed in rage. Michael recognised the signs. Danny was becoming irrational.

“No,” Patrick protested. “I told you, my family were murdered too. My father… my father tried to get into the command ship, to stop them. But they caught him and exterminated him along with all the prisoners they took that day. My mother died later. I was alone. If it wasn’t for friends like you, I don’t know what would have happened to me. I was happy even though I was alone, being part of the gang, with you and Larry and Michael.”

“You’re ONE OF THEM!” he screamed again, his own grief blinding him to all logic, all sense. He lashed out with his fists towards Patrick, pulling him to the ground, hitting at him with all the same ferocity Michael remembered from the fight in the park.

“Danny, NO!” he yelled as he ran towards them. He had seen the alien reach for a weapon, seeing only somebody attacking one of his own, not a troubled boy too grief-stricken and confused to see sense. He aimed the gun, ready to fire as soon as he had a clear shot.

Michael grabbed him and rolled him away, covering him with his own body, even though Danny was too mad with grief to realise he was now fighting Michael again. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Patrick stand up and put his body between them and his alien friend. He put his hand up and said something urgently in his own language. The alien lowered the weapon but did not put it away.

“I’ve told him you’re friends, not a threat to me,” he said. “He is here to protect me. If you attack, he will kill you. It is his job to make sure I am not hurt… So just stay calm and we’ll all be ok.”

“We’re going,” Michael said, pulling Danny up and holding onto him with his last ounce of strength. “I didn’t know… I thought you were one of us. Are you going to be all right? Your planet, where you come from…”

“It’s a beautiful place. I’ve missed it so very much. I loved Earth. Even after the war, when it was a mess, it was still a great planet. But I want to go home now. I’m glad you’re here, in a way. To say goodbye. They told me not to say anything, to just come to the rendezvous, but I am glad you’re here.”

“Patrick…” Michael said. “Goodbye. Good luck. Danny, please. Say goodbye to him. He’s our friend and he’s leaving now.”

Danny couldn’t bring himself to say anything, but he was calmer now. He had stopped raging and struggling.

“Goodbye,” Patrick said, then he stepped into the light with the alien. There was a shimmer and for a moment the boy they had known appeared as a green and red-orange alien, his true form. Then the light was gone, and so were they. Michael waved as he watched the ship begin to ascend. Almost as quickly as it arrived it was gone.

“Come on, Danny, let’s get back,” he said. “We’ll go to the nurse and tell her you had a bad dream. She’ll give you something to make you sleep. And tomorrow, when they ask about Patrick, we won’t know anything. Ok.”

Danny said nothing. But he walked with Michael’s help. There was a long silence for a while. Then movement in the gallery above the once plush boxes.

“Well,” The Doctor said. “I never saw that coming.”

“Did you recognise the species?” Chris asked him.

“Oh, yes. Felluxians. Decent people. Great travellers. Explorers. They like to blend in with the indigenous species and study their lifestyle. Brave too. His parents… they got stuck in alongside the Humans, fighting the Daleks.”

“That’s what happened to Patrick. He went home.” Michael was still taking it all in. He gave a gasp of surprise. “It’s changed. My memory of what happened. I wasn’t in hospital. I was in the room with them. I woke and found them both out of bed. Followed them. And…”

“And you grabbed Danny, pulled him away from Patrick. So he wasn’t shot by the Felluxian.”

“He didn’t die?” Chris looked at The Doctor for confirmation. “He didn’t die. Things changed?”

“He didn’t die,” Michael said. “He had a hard road to travel. He needed a lot of therapy, a lot of friendship to pull him out of it, but he made it. He lives in Ashford, in Kent. He’s got a small business of his own. He writes from time to time.”

“How come?” Davie asked. “You always drilled it into us that we can’t change things. You told Michael we could only observe.”

“Yeah, and then I went and changed things, by repairing Michael’s concussed skull and saving him a night in hospital. So he was in his room when Patrick and Danny went out. I changed things for Michael. And that, in turn, changed what happened.” The Doctor sighed. “We pushed the envelope. It was the younger Michael, who belongs in this time, who actually stopped him being killed. That’s the only reason we don’t have a major paradox here.”

“But Danny’s alive,” Michael said. “That’s good, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is,” The Doctor agreed. “It’s fantastic. He had a chance to find peace. It burnt me up inside seeing him so hurt, and knowing he was going to die with all that rage and pain inside him. I’m glad. But we can’t push our luck. Next time it’ll be the reapers and the world turned inside out.” He sighed again and then smiled brightly. And for the first time since they started this misadventure in time he actually wasn’t putting the smile on. It had been painful, but painful like having a tooth pulled. He felt better for it. He thought they all did.

He looked at his watch as they came to the TARDIS, discreetly parked in what used to be the organ pit. “I’ll get us back by about 11.30. Time for another quiet drink and then, I don’t know about the rest of you, but I’m going to go to bed to snuggle up to my beautiful, if a little sniffly, wife.”

|

|

|