Jean turned the Swann light bulb around slowly to find the very tiny letters etched in the glass that pointed them to the next stage in their quest.

“Hat on for the bluecoat boy’s cap,” she read.

The Doctor smiled enigmatically.

“You work it out this time. Have fun with it.”

Jean read the clue again.

“Bluecoat Boy… Well, Bluecoat Schools in the old days were charity schools for destitute children. They had a distinctive blue uniform. I wrote quite a good essay about them in sixth form college. I discussed whether the uniform stigmatised them as paupers or was worn with pride because they were being educated to rise above their poor beginnings. I came down on the latter side, because in Victorian times there was a big emphasis on people bettering themselves through education, and there wasn’t the same snobbery about designer labels we have now that would have made the kids feel self-conscious about their uniforms.”

She wondered if she was starting to get like The Doctor – rambling on. He was listening to her, though. Maybe she was making sense.

“The cap refers to part of the uniform, of course. But we’re not seriously going to steal a pauper boy’s cap. That would be nasty. Besides, what’s this ‘Hat on’ bit about?”

The Doctor said nothing. This was her puzzle.

“Hat on… hat on….” She repeated. “Wait a minute. That sounds like… Haton… Hatton… there’s a place in London… Hatton Gardens. Do you think….”

The Doctor continued to smile enigmatically as she went to the TARDIS database and looked up Hatton Gardens. She discovered that it was named after an Elizabethan owner of the land, Sir Christopher Hatton, and was famous as the traditional centre of London’s diamond trade. That seemed to suggest that she was on the wrong track, but a simple Google search for Hatton Gardens and ‘Bluecoat’ revealed that there was a Bluecoat School in the Gardens opened in 1696. The façade of the building, which had been damaged in the Blitz and was now office space, still bore two statues – a bluecoat boy and girl.

“We need the cap that the boy statue is holding,” Jean said, looking at a picture of the statues. “Any thoughts?”

“None that are legal,” The Doctor answered. He glanced at the collection of souvenirs already gathered. They had trespassed in the House of Lords and committed an act of vandalism and a public order offence in order to get them.

“I think we’re past caring about that, Jean pointed out.

“Pick Nelson’s Spare Nose!” Rory read the message written on the side of Winston Churchill’s cigar.

“Uggh,” Amy responded.

“I don’t think that can possibly mean what we think it means,” River commented dryly. “I certainly hope not, anyway.”

“It doesn’t,” Rory assured the two women. “I know what it means. I read it on an urban myth website. River, dear, set our destination for Admiralty Arch.”

“What year, father dear?” she asked.

“This year will be fine,” he answered. “Make it early in the morning, though, when there’s not much traffic. Not too early, somewhere between house burglar and jogger.”

The Doctor and Jean arrived in Hatton Gardens early, too. The Doctor was wearing overalls and carrying a ladder, a paint brush and a bucket of paint. Jean was dressed as a respectable member of the public who merely watched curiously as he set up the ladder and climbed up before starting to repaint the statue of a girl in a blue dress with a white apron. The statue was obviously very old and in need of restoration. The apron was badly flaking and the girl’s face was cracked and missing the signs of rosy cheeked health it ought to have had.

The odd thing was that he only had one brush and one pot of paint, but he somehow had all of the colours, blue, white, as well as shades of flesh pink, red and yellow, to complete the refreshing of the statue.

People passing by looked up to see what the man was doing on the ladder. They saw the little statue being given a long overdue makeover and carried on walking. Even a man coming to open up one of the offices in Wren House itself merely nodded and said good morning to The Doctor as he walked past the ladder.

When he was done with the girl The Doctor relocated the ladder and started on the boy figure, touching up his blue suit of knee length yellow trousers and white socks with a little blue frock coat and restoring his badly cracked face. When he came to the beret-like cap held in the boy’s hand, The Doctor carefully detached it from the plaster fingers and put it in his pocket. When he descended from the ladder the boy was holding a blue plastic Frisbee that matched the colour of his coat.

“People will NOTICE,” Jean told him. “Eighteenth century paupers didn’t play with Frisbees.”

“The cap will be put back later,” The Doctor assured her. “That’s the rule of Mornington Crescent. Everything gets put back. But I think that’s an acceptable substitute for now, and don’t they both look nice and smart?”

“Yes, they do,” Jean agreed. “They look lovely. I didn’t know you were so artistic.”

The Doctor grinned as he folded down the ladder and carried it, along with the paint and brushes, back to the TARDIS, telling her one of his tall stories about his friendship with Leonardo de Vinci.

“It’s an urban myth,” Rory explained as Team Pond approached the gracefully curved office block and road traffic calmer in one called Admiralty Arch. “On the wall of the traffic arch leading out of Trafalgar Square, just above head height for an average man is a sculpted nose. The story used to be that it was put there when Nelson’s Column was built. It was meant to be a spare nose for the statue in case it was damaged. Another story is that it was meant to be a cast of Wellington’s Nose, set at a height where soldier’s on horseback could rub it for good luck.”

They really weren’t supposed to be under the traffic arch. Pedestrians had their own, smaller arches either side of the main ones, but it was very early in the morning and there wasn’t much traffic. They had time to find and closely examine the ‘nose’.

“Either story sounds plausible,” Amy said.

“Yeah, except that Admiralty Arch wasn’t built until about seventy years AFTER Nelson’s Column was built, and a long time after Wellington snuffed it, too,” Rory said. “And in 2011 a sculptor called Rick Buckley admitted that HE put the nose up there in 1996 along with a whole bunch more of them all over London.”

“So how did people get the idea that it had been around longer?” Amy asked.

“That’s the thing about Urban Myths,” Rory answered. “Nobody ever says things like ‘hang on, it’s only been there for, like, a decade and a half.’ They say ‘oh, yeah, I remember my granddad telling me about it when I was a kid,’ and stuff like that.”

“Well, if it’s just a piece of urban graffiti then it’s not really illegal for us to pinch it,” River said. “Not that it would bother me if it was. I mean, I’ve done a lot worse.” Her parents both looked at her disapprovingly but she just grinned and adjusted her vortex manipulator. She aimed a thin white beam at the nose. The glue sticking it to the wall weakened and it dropped suddenly. Rory caught it neatly. The three of them quickly walked through the archway, back to Trafalgar Square, and sat by Admiral Nelson’s lions to examine the nose for the next clue in their quest.

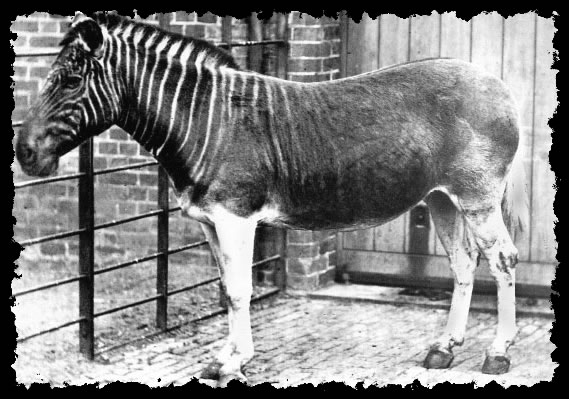

“Ride the last Shilibeer in London,” Jean read on the inside of the bluecoat boy’s plaster cap. “What on Earth is a Shilibeer? And why is it the last? It had better not be some poor near extinct animal in Regent’s Park Zoo, like the Quagga or something, that they let big fat humans ride on until it drops dead of exhaustion. I don’t hold with that kind of thing. It’s as bad at the stupid tourists up around the islands wanting to swim with the seals or some rubbish like that.”

The Doctor waited patiently for her to stop talking.

“Have you any particular objection to horse drawn carriages and the like, in the era before the invention of motor power?”

“Well, I suppose that’s different,” she replied. “As long as the horses are well cared for, and not pulling more than they can manage, and it’s for transport, not just for silly amusement, then it’s ok, kind of.”

She was having to backtrack on her principles a little, but when she thought about it, she really couldn’t think of any reason why horse drawn transport was wrong.

“Nobody, incidentally, ever rode the Quagga at London zoo. It was well looked after and lived to a ripe old age, even if it was rather lonely, being very nearly the last of its kind anywhere on the planet,” The Doctor pointed out. “And a Shilibeer isn’t an animal. It’s a horse drawn omnibus, the ancestor of the good old London Routemaster and the Boris-bus. Shilibeer was the name of the chap who built and ran the first of them way back in 1829. The last of them was in 1911, before the motor omnibuses took over completely.”

“So we’re going to 1911,” Jean said. “That calls for a totally new outfit. Late Ewardian….”

“Dress warm,” The Doctor told her. “The last trip was in October, and it was evening.”

“Great, we’re off for a wet, cold bus ride in the dark. You take me to some of the most romantic places, Doctor.”

“We’ve got to go and see the Quagga in Regent’s Park,” Rory said, squinting at the words etched on the part of the nose that had been stuck to the arch for posterity.

“What’s a Quagga when it’s at home?” Amy asked.

River smiled enigmatically. Her parents both looked at her expectantly.

“The Doctor took me there once – one of his romantic afternoons. He wore authentic Victorian clothes and got rid of that silly bow tie for once. I wore russet velvet. We had tea in the zoo café. He was an absolute gentleman, of course… at least until we were back in the TARDIS again.”

“That’s far too much information, dear,” Amy told her. “About your date with The Doctor, anyway. Far too little about the Quagga and what it has to do with anything.”

“It’s an animal at the zoo,” Rory guessed. “That’s what you’re saying? London Zoo in Regent’s Park.”

“Well, that’s easy enough. The zoo is open all year round,” Amy said. “But what the heck is a Quagga? I’ve never heard of it. It must be one of those obscure animals that they do breeding programmes with in captivity and return to the wild.”

“I’m afraid not,” River said with a sad shake of her head. “Gather round, mum and dad. We need to take a trip back in time. Shame I don’t have that russet velvet available. It really turned heads.”

Jean had the whole of the Wardrobe to choose from and stepped out into the blustery evening of October 25th, 1911 dressed in a warm woollen skirt and a linen blouse topped by a warm coat. She appreciated it straight away. The omnibus stop outside of London Bridge railway station was open to the elements. She was glad she had chosen a bonnet style hat that she could tie down and not worry about. She spotted a gentleman chasing a rather less robust hat belonging to his lady friend and was full sure The Doctor wouldn’t do that for her.

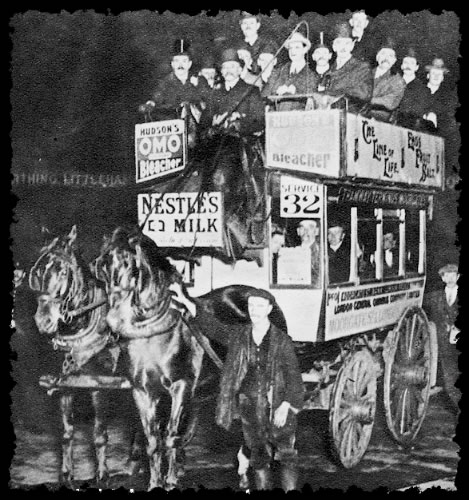

The omnibus arrived. It was pulled by two strong horses side by side in what Jean thought were called ‘traces’. A man jumped down to unhitch them as the passengers alighted from the platform at the back much as they did on the later Routemaster buses. The omnibus was a dark brown-red colour covered almost everywhere it was possible to cover it with advertisements. There was one for Omo bleach. Jean vaguely remembered there used to be a brand of washing powder called that. Another was for Enos Fruit Salts, and one for Nestles Milk as well as some products that hadn’t stood the test of time. A fresh pair of horses were hitched up and new passengers were allowed to get aboard.

“We’re sitting downstairs,” Jean insisted as The Doctor glanced longingly at the staircase to the open top deck. He sighed theatrically and followed her to a double seat. She took the space by the window and he crammed beside her. The omnibus was narrower than a modern bus and the seats, merely wooden slats, were by no means comfortable. It was a long time before sprung upholstery.

The bus was very crowded by the time it set off. Far more people seemed to have gone upstairs than Jean thought possible. She thought of those trains in India where people sat on the roof when it was full inside. It all seemed rather unsafe in her opinion. Perhaps it was a good thing that this was the last time the horse omnibus was going through the streets of London.

It was hardly the smoothest of rides, either. The suspension beneath the omnibus carriage itself was minimal if not totally non-existent. Jean couldn’t even see much outside the rain covered windows. Most of the men on the bus smoked, too, something that had been banned on public transport for most of her adult life. She wasn’t against smokers as such, but she found the sheer number of them in such a small space overpowering.

“How far do we have to go?” she asked The Doctor.

“All the way, I suppose,” he answered, feeling very glad that River Song, or, even worse, Captain Jack Harkness, wasn’t around to make an innuendo out of that snatch of conversation. The conductor was at his side a moment later and he purchased two tickets all the way to Moorgate. Jean wasn’t even sure how far away Moorgate was but she was calculating her chances of getting there without being ill. “Then again… perhaps not. I think we have our clue.”

He studied the very small ticket in his hand carefully, holding it up to his eye to read the small print. “Yes, we can get off at the next stop if you want.”

“I WANT, very much,” Jean insisted. But there really wasn’t any way of getting off the omnibus. It was quite full with new passengers pushing in to stand between the seats. She closed her eyes, took a deep breath and resigned herself to being stuck aboard until the end.

“Here,” The Doctor said, pressing something into her hand. She opened her eyes and looked at the sweet and for some odd reason a scene from the film Charlie and the Chocolate Factory came into her mind.

“It won’t make me spit in multi-colours, will it?” she asked cautiously?

“No, it’s an Alturian motion sickness lozenge. Don’t worry, it stops it, not creates it.”

She sucked the sweet. It tasted fruity, but she didn’t dare ask what sort of fruit it was meant to be. The nausea passed, anyway, and the smell of various brands of tobacco began to seem less unpleasant. She managed to enjoy the historic ride on the last omnibus.

Even so, she was glad to get off that now redundant transport when at last they reached Moorgate. She breathed deeply and appreciated the night air of London, even though it was smoky and polluted compared to the clean air of her island home.

“So the clue is on the ticket?” she said to The Doctor. “All we need to do is get back to the TARDIS.”

“Three-quarters of a mile back the way we came,” he confirmed. “Would you like to try the London Underground?” He waved towards Moorgate Station. “Or if you like we could walk. The rain seems to be easing off. It could prove to be a fine night.”

“Let’s walk,” Jean decided. “We seem to be rushing about all over the place on this quest. If we have time, let’s just enjoy a stroll.”

That decided, The Doctor suddenly dashed away across to a vendor outside the tube station and dashed back again holding two paper bags gingerly. They proved to contain hot chestnuts. With thoughts of Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins floating through her mind Jean tasted the food treat and decided they were the perfect addition to their walk. She ate the hot, soft, crumbly chestnuts and took notice of the streets they had travelled down without properly seeing before.

“Lombard Street,” The Doctor commented, between mouthfuls of chestnuts as they came to a junction. “I remember years ago when I did this before, I had to find the gilded grasshopper of Lombard Street. I had to use a bit of trickery to get it.”

As they passed down the street known as the centre of London’s financial district before Canary Wharf was remodelled, Jean noted that pictorial signs hung from almost all the buildings. It was a variation of the same kind of tradition that saw red and white poles on barber’s shops or inventive signs outside pubs.

One such sign in Lombard Street was a gilded grasshopper on a wrought iron frame hanging from a pole. Two people were looking up at it very intently. The Doctor grinned.

“A couple of our fellow Questers,” he said. “The same old clue being recycled.” He took out his sonic screwdriver and aimed it at the grasshopper’s frame which promptly dropped off the pole into the arms of the very surprised gentlemen. The Doctor waved his hand to them. “Good luck, chaps,” he called out. They returned the gesture before disappearing with the signature twinkle of light that suggested a Time Agent’s vortex manipulator.

“That was nice of you, helping them out,” Jean said. “But aren’t you worried they might have the edge over you now?”

“Not really. We only have one more souvenir to pick up and I know exactly where to go to find it.”

London Zoo in 1870 was not the place it was in the late twentieth century when Rory and Amy had visited it on a school day trip. There were no wide, open plan compounds for the animals based on their natural habitats. They were all kept in cages with a bit of hay on the floor and at best a bit of a swing for the monkeys or a pool of water for the sea lions.

The Quagga was a little better off than the really fierce animals like the lions and tigers in their fully enclosed cages. At least it was in a sort of paddock with the railings up to waist height. Amy reached out and stroked its nose and it seemed to appreciate the gesture.

“It’s a sort of half zebra,” she said. “Stripes on the head and shoulders fading into a chestnut brown like an ordinary horse.” She smiled. “It’s lovely. But do you really mean it, the poor things are nearly extinct, now?”

“That’s what The Doctor said when he brought me here. In Africa, where they come from, they’ve been hunted for meat and driven off land wanted for cultivation or grazing cattle. He’s really fierce when you get him onto the subject of extinction. I suppose… being nearly extinct himself….”

“Yes, I know,” Amy agreed. She had seen that side of The Doctor herself, not the least when they found out the truth about the space whale that bore Starship UK on its back.

“It’s a shame,” Rory said. “If it was in our time they would get a male with her and breed them and see about sending the young to reservations in Africa to live in the wild like they should.”

“If The Doctor wasn’t so strict about timelines and not interfering he’d donate a male to the zoo now and they could get a head start,” Amy commented. “But of course, he won’t. So… I suppose we just have to consider ourselves privileged to have been so close to this lovely old girl.”

“What does it have to do with our quest, though?” Rory asked. “We’re certainly not taking her down the escalator at Mornington Crescent.”

The idea made Amy and River both laugh. But the fact remained that they had no idea what they were supposed to do. They looked at the small guide to the animals in the zoo that they bought on the way in. It was a long way from the glossy, informative booklets they knew in their time, and it didn’t seem to have any secret messages in it.

“Wait,” River said just as they were starting to wonder what to do next. “Look at that.”

She pointed to the top metal bar around the Quagga’s paddock. There were scratches on it that looked almost like letters.

“The top half of letters,” Amy said, tracing the scratches. And… look… on the next bar down… those are the bottom half. Rory, take a photograph of the bars with your phone.”

“Make sure nobody is looking,” River added. “Your phone won’t be in the shops for another one hundred and forty years.”

Rory glanced around, then stood close to the railing and photographed it. He took several photos to make sure he got the two sets of half letters, then he stood back and took some pictures of Amy stroking the Quagga’s nose. They were unique images. He didn’t care what anyone, not even The Doctor, said about timelines and whatever. He intended to keep them for posterity – the only COLOUR images of a living Quagga.

“Let the poor thing alone now, sweetheart,” he told his wife. “We can go and see some of the other animals for a bit before we go. But no trying to bring any of them home with you.”

“Find A Street Cannonball At Victoria’s Victuallers,” The Doctor said with a smile as he programmed their destination in time and space.

“I don’t get it,” Jean answered him. “Cannonballs are not usually lying around in the streets of British cities, and I don’t think there has ever been a time when they were. Even when London was walled and defended, cannonballs weren’t in the streets. They were in the guardhouses or whatever.”

“Actually, cannonballs are a very common sight in towns and cities all over your country,” The Doctor replied. “You pass them all the time without ever thinking about them, completely taken for granted. But these particular examples are quite nice ones.”

The TARDIS materialised against a high brick wall. It was blackened with accumulated soot, telling Jean that they were any time between the onset of the industrial revolution and the Clean Air Acts of the mid twentieth century. The clothes worn by the mainly male crowd gathered in the street were not a lot of help narrowing things down. Working men’s attire didn’t seem to change much in that era, being mostly hard wearing fabrics and an assortment of caps. The better class men who gathered near an elaborately decorated entrance to some sort of factory or yard were in tailored suits and frock coats with top hats. Again it could have been any time between Victoria’s coronation and that of her grandson, George VI.

“It’s 1858,” The Doctor said, solving the mystery. “And we’re at the Admiralty Victualling Yard at Rotherhithe awaiting a visit by Queen Victoria herself, after which, by Her Majesty’s decree, this will be known as Royal Victoria Victualling Yard.”

“She must have been… or will be… impressed,” Jean commented. “Victualling… so it’s where food and drink and whatever is stored and distributed to the Royal Navy ships? Yeah, I get that. During the war, they did a lot of that sort of thing from Rothesay and the other port towns of the islands.”

“Exactly that sort of thing,” The Doctor agreed. They were aware of a growing wave of excitement amongst the crowds as a troop of mounted guardsmen preceded the royal coach. Jean got a glimpse of a still attractive woman in her late thirties dressed in white and blue. She was accompanied by her Prince Consort and smiled at the subjects cheering as the coach passed between the elaborately decorated gate posts into the yard.

The gates were closed on the general public as soon as the carriage and escort were inside. The Doctor and Jean were in the general public, of course. The queen’s visit wasn’t the reason they were here, after all.

“That’s what we came to see,” The Doctor said as the crowds drifted away from around the gate. “Do you see the four bollards either side of the road, painted white at the top so that they show up at night and guide horse drawn wagons into the yard.”

“I see them,” Jean answered.

“What do they look like to you?” The Doctor asked.

“Bollards. Just like any other bollards except for the white around the top. Mostly they’re black painted. There are millions of them around the streets.”

She looked again. The Doctor had told her that what they sought was commonly found in ordinary streets, even in her own time, and these bollards were perfectly common looking.

She tilted her head and looked at them sideways. Two of the bollards were already leaning slightly, which helped to see them at a new angle.

“Wait a minute… are they…. Were these bollards made from old cannons out of a navy ship, something from the Battle of Trafalgar or whatever?”

She thought about it a bit more.

“Are you telling me that ALL the bollards I’ve walked past without thinking are made of old cannons?”

“All of the really old ones, anyway,” The Doctor replied. “Of course, councils have replaced street furniture over the years. Some have copied the old shape, others have gone for boring straight up and down steel ones. But a lot of them are disused ordnance.”

“And the round bit at the top… that I always thought was just ornamentation… would be a cannonball?”

“Exactly.”

“I never even knew that, and me with a post-grad. in history. I’ll bet hardly anyone really knows about them. It’s a real swords to ploughshares thing, using old weapons for a peacetime purpose, isn’t it?”

“Absolutely.”

“Those cannonballs must be welded in really tightly, though. I don’t see how we could get one of them.”

“Today, we can’t. There are far too many people about. And I don’t think any other time while the yard is doing business would work, either,” The Doctor admitted. “But I knew you’d enjoy seeing things as they used to be. Let’s head back to the TARDIS.”

They did so, and a few minutes later according to Jean’s watch, they rematerialised in the same place in 2012. Jean spent several minutes comparing her memory of how it looked when Victoria visited to how it looked now. The wall either side of the gateway was a warm, clean cream colour now there was so much less air pollution and there were no vicious looking iron teeth at the top. The gate was gone, replaced by a wrought iron archway with a retro-looking electric lamp hanging down.

And the warehouses, abbatoir, pickling house, cooper, brewer and distillery were all gone, now, replaced by the Pepys housing estate, named, obviously, for Samuel Pepys who worked for the Admiralty at one part of his colourful career. The gateway was just a rather interesting and unusual entrance to the residences.

The bollards were still there, still painted black and white, two of them still leaning drunkenly.

“When I was an undergraduate I loved things like that… looking at an old picture or an old map of somewhere and then at the present day image, and seeing what traces of the past remained. You’ve let me see it with my own eyes, which is AMAZING and utterly fantastic.

The Doctor smiled and looked around. The street was quiet. It was early on a Sunday morning in June. The residents of Pepys estate and the rest of modern day, gentrified and revitalised Rotherhithe were either asleep or just putting the kettle and toaster on. Nobody witnessed him use the sonic screwdriver to loosen the welding that had been in place for getting on for a hundred and eighty years and pocketing one of the cannonballs. Nobody saw him put an old leather cricket ball in its place.

“I got that at the 1900 summer Olympics, in Paris,” he said. “Britain bowled out France with five minutes to go and I picked up the ball while nobody was looking. I hope it’s still there when I come back later and put the cannonball back. It’s got a kind of sentimental value.”

“You, sentimental?” Jean was sceptical. What’s the message?”

The Doctor turned the cannonball, holding it as if he was about to bowl it to an invisible batsman. He smiled widely as he found the message in the hemisphere that had been welded inside the cannon for so many decades.

“Well done my honourable quester, you have completed your tasks. Return now, post haste, to Mornington Crescent. The first to return wins the grand prize.”

“To the TARDIS?” Jean asked.

“To the TARDIS,” The Doctor replied.

“Find an ancient pile with Magnus the Martyr,” River said, reading the clue they put together after downloading the images from Rory’s phone back at a twenty-first century internet cafe and using Photoshop to put the two half images of lettering together.

“I met Magnus, once,” Amy said. “The Doctor and I had dinner at his castle in the Orkneys. He was joint ruler of the islands with his cousin. Poor guy was put to death because the locals were all scared there would be war if two Earls tried to rule the islands together. His cousin’s cook wacked him over the head with a cleaver and split his skull. He forgave him first and prayed for him. That’s why he was made a saint. The Doctor said it was always trouble when there were two heirs in any family. I always thought it was some kind of clue about his own homelife, but you know what he’s like… little hints and no whole stories.”

River nodded solemnly. She knew all about strange dinner parties with The Doctor’s assorted friends, and about those rare glimpses of his background.

Rory tried to be solemn but he couldn’t help the image that had popped into his own head.

“Magnus Magnusson. He is a bit of an ancient pile himself by now.”

“I’m sure he’s not the clue,” Amy told her husband. “I think we need to do a bit of Googling. If he’s a saint, maybe there’s a church in London. It’s a long shot, seeing as he’s a Norwegian associated with Scottish Islands, but you never know.”

It turned out not to be such a long shot after all. The present day Parish Church of St. Magnus the Martyr was another of Sir Christopher Wren’s designs replacing the church burnt down in the Great Fire. It was near London Bridge, and dedicated to Fishmongers and Plumbers. The first made sense since it was also near the Old Billingsgate Market. The second was a little less obvious.

Further down the Wikipedia page though, they solved the mystery of the ancient pile. Rory closed the page and turned away from the internet café computer, pocketing his phone and its blue tooth attachment for transferring files. River programmed the vortex manipulator for a short journey.

“Lovely old building,” Rory commented when they stood on the pavement outside the seventeenth century church with a remarkably continental look to it, enforced by the steeple added twenty years after the original church was finished and modelled on one the architect saw in Antwerp.

“It looks swamped by all the modern buildings around it,” Amy added. Even the newly built Shard towered over it along with more mundane but equally lofty glass and steel buildings. The church looked as if it was the last vestige of a time long gone. She hoped it had some sort of listed status or it might well be swallowed by modernity.

They knew exactly what they were looking for here. They passed through an open gateway to the passageway under the steeple that used to be a public walkway to the old London Bridge – the one that was always falling down in the nursery rhyme. In an alcove there were two strange relics of the past. One was a thoroughly old fashioned fire hydrant that might have been the connection between the church and plumbers or a remembrance that the church had to be rebuilt after the fire that began only a very short walk away in Pudding Lane. The other was a really old, blackened stump of wood bound up with strips of metal, presumably to prevent it falling completely to pieces. There was a metal sign screwed to the wood.

“From Roman Wharf AD51 found at Fish Street Hill 1931,” Rory read aloud. “That’s our ancient pile – or more correctly, part of the piling from an old Roman Bridge that crossed the river around about where the new London Bridge is now.”

Even for three people who had very personal connections with the Roman occupation of Britain, that was an awesome thought.

“This lump of old wood has been around here longer than I was waiting with the Pandorica.” Rory summed it up neatly for them all. He touched it reverently, and without being at all disappointed not to sense some deep connection between himself and the Romans – or more likely their slave workers - who had sunk it deep into the muddy river bed. “I don’t know what your man in the station wanted us to do, but we’re definitely not knocking off bits of that. It would be sacrilege.”

Amy and River didn’t dare dispute him. There was a fiery look in his usually gentle eyes.

“We’ll take the plaque,” River decided. “It’s only screwed on. It will go back, good as new, later.”

“All right,” Rory agreed. He took River’s futuristic ‘sonic screwdriver’ from her and used it as a screwdriver for possibly the first time in its history. He detached the plaque carefully, noting that it had etched the shape of itself into the wood and left a slightly rusty discolouration behind, but nothing that would further degrade the ancient timber. He touched the indentation carefully and noted that it was dry. He also noted a very faint trace of lettering embossed on the wood. He looked at the back of the plate and saw raised words, but back to front like a secret message from Leonardo da Vinci. The message to the Questers was on the wood itself.

“Congratulations, my friends. Bring your treasures to Mornington Crescent first and you will be rewarded with a greater treasure.”

On we go, then,” Rory said. “To the Station.”

Team Pond arrived at the top of the escalator just as the station-master had set them going ready for the first passengers of the day. He looked at them in surprise and commented on them being early birds. He looked curiously at the snooker cue bag with a woolly hat on top in which Rory had concealed the iron paling with pineapple from the Church of St Andrews, Holborn but could see no reason to stop the passenger taking it on board a train. Rory was relieved. He was fairly sure that a long spike of wrought iron might be construed as a potentially lethal weapon and banned from the station.

The platform was empty when they reached it, but moments later they heard a very familiar sound and a blue police box materialised in a puff of displaced air. The Doctor and Jean stepped out loaded up with their curious selection of souvenirs.

“We were here first,” Rory said. “So get in line.”

He glanced up the escalator. The tall thin and short fat pair of questers were coming down the stairs. The short fat one was holding a wrought iron frame with a large gilded grasshopper on it. The tall thin one had another snooker cue bag that proved to contain a long steel arrow taken from the statue of Diana the Huntress in Hyde Park. They both looked disappointed to find other Questers had got there before them.

“My friends!” They all turned to look as Lord Sweetwell emerged from what Jean had christened as platform nine and three-quarters accompanied by his entourage. “You have returned. Let me see, which of you was first?”

“They were,” The Doctor admitted, pointing to Team Pond, who stepped forward and presented their souvenirs.

A few minutes later Team Pond and The Doctor and Jean stepped back out of Mornington Crescent station together into the cool but bright Camden Town morning. Unencumbered by their souvenirs of the Quest, they headed towards a café that promised real coffee and all day breakfasts. While they waited for their orders they all looked at the prize.

It looked like a very small coin purse from an era before the need to store credit cards in a slot. It had rather unattractive beadwork around it in a swirling pattern and was, frankly, ugly. But when Amy opened it, she took out the cost of four breakfasts, coffee, and a generous tip for the student trying to supplement his loan who served them. She closed it again, knowing that the next time she needed money there would be exactly what she wanted in it.

“A bottomless purse, unlimited, universal, endless credit,” she said. “We would never need to worry about money again.”

“We don’t have to worry about money, now,” Rory pointed out. “None of us do. It’s an amazing prize. But….”

As they all considered the enormous responsibility that went with having everything they ever dreamed of, a man came and sat on the pavement in front of the window where they were sitting. Even from the back they could see he was a down and out. Amy looked at him thoughtfully and then reached into the purse. She folded her hands around the money she took from it so nobody else could see, then she went outside and gave it to the homeless man. A few minutes later they saw him go to the take out part of the same café they were in and get a large cup of hot, steaming coffee with a lid over it and a bacon and egg barm in a polystyrene tray.

“You know, he might be hungry now, but later he’ll probably just buy drink with the rest of the money,” Rory pointed out.

“That’s his choice. I didn’t put conditions on the money,” Amy said. “We DO have enough money for everything we really need. But what if… what if we use this so that every time we see one of those adverts about the NSPCC or MacMillan Nurses, or Donkey rescuers in India, or every time we see somebody in the street collecting for charity, we can do more than walk past. What if we use it to do some good, to make a difference. What about… I don’t know… the Melody Pond Foundation for helping worthy causes?”

Jean was on the point of asking who Melody Pond was, but she decided it didn’t matter. It seemed like Amy had the right idea. Everyone was nodding in agreement, especially The Doctor, who didn’t seem to be at all disappointed to have lost the Mornington Crescent Quest for the Eleventh time.

|

|

|