Marie Reynolds looked around her classroom and tried to work out what was wrong.

It was March. The flu season was over. The entire Doyle family were off school because they had mumps, but that was just one child in each classroom. It didn’t account for how quiet this room was. There were chairs and tables for thirty-five children, which was too many for a modern classroom where more was required of a teacher than dispensing rote learning to all with no time for individual needs.

But something didn’t seem right. She was certain she ought to have more than fourteen students. This was an overcrowded, underfunded school in a depressed catchment area. Large classes were normal. She had seen five years of coping with all the problems it entailed, from not enough chairs to not enough time to give to each individual child.

She tried to think who was missing. On the edge of her memory she almost thought she could see faces, hear names, recall the social or medical problems the kids had.

But then the faces, the names, the notes about incontinence, dyslexia or ADHD all evaporated.

She glanced at the register. There were fourteen names on it. She looked around and saw those fourteen students hard at work on English comprehension.

Nobody was missing.

But why did it feel as if they were?

Who were all the empty chairs for?

“Miss?”

Frankie Gerard put up his hand urgently. He had a note about incontinence. She nodded wordlessly and he rushed out of the room.

Liam Boyle hadn’t put a hand up. He almost never did. His confidential notes said that he had been admitted to hospital three times with self-inflicted injuries. He never seemed happy, though Marie had no idea why. He was eleven years old. There was nothing to be miserable about, yet.

That was still to come when he got to secondary school.

She came to his side, prepared to help with whatever he was struggling with. She noticed him slipping an iPad under his pile of text books. She glimpsed the familiar blue Facebook top banner before it was hidden.

“Social media can wait until hometime,” she whispered. It was ABSOLUTELY against the rules, but it was, as far as she knew, his first offence so she was letting him off easy. “How are you doing with your essay?”

He answered in the usual few vague words that she was used to from students. ‘Not good at verbal communication’ was a common notation in school reports. She gave him some pointers towards his written communication and hoped that was enough for now. Sometimes she did wonder if she could be a better teacher than that and finally engage with them all.

But it was Friday and all she could think of was spending the weekend somewhere more interesting than Tallaght.

She went back to her desk and looked at the clock slowly sweeping around to three o’clock.

A few minutes before the golden hour she wondered if somebody ought to be in the classroom who wasn’t. Had somebody gone out and not come back?

If so, who? She couldn’t think who was missing. She did a quick headcount. All present and correct. An uneven and not so unlucky thirteen, all ticked off in the register.

At last it was three o’clock. The bell rang. She resisted the urge to run out of the classroom to freedom and made her students do the same. Just as the last one had left the room in an orderly manner she heard the sound she had longed to hear. Badly spelt essays wafted off her desk in the sudden draught from the stationery cupboard. She wrenched the door open, then the other door inside that one.

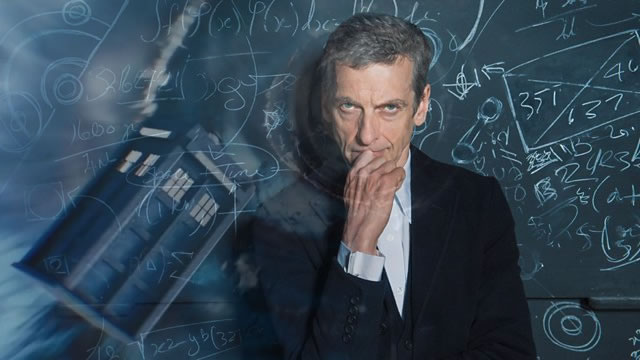

“Just… take me anywhere,” she said as she closed the TARDIS door and ran to the console. On the big screen the stationery cupboard dissolved into the time vortex. “Five days of teaching. I didn’t even bring marking. I just need a complete break.”

“Complete break it is,” The Doctor answered with a toothy grin. “Though… I hesitate to mention it… but you left a pile of marking last weekend.”

He pointed to a stack of grubby exercise books on the sofa.

“I wondered where they went,” she said. “Well, they can wait, too. Take me somewhere awesome.”

“That’s a dangerous ask.”

But he brought her somewhere awesome, and for once, without danger to life or limb. She had the sort of break from being a teacher that she needed.

He brought her back to the stationery cupboard at half past eight on Monday morning, just in time to get ready for the influx at the stroke of nine.

He must have been feeling kind, because he carried the pile of marking out of the TARDIS for her. He made out that he was just getting rid of her mess out of the console room, but she wasn’t fooled.

“They all look like d-minuses to me,” he commented as he set the pile down on the nearest flat surface.

“Oh, some of them aren’t that bad,” Marie responded, opening the register and getting herself ready for the day. “Kyle Lonergan is quite bright when he bothers to pay attention.”

Then she glanced at the register and frowned. She checked the list of twelve names from top to bottom even though they were in alphabetical order.

“Who did I just mention?” she asked.

“Kyle Lonneegan,” The Doctor answered. “Is this a trick question?”

“There… isn’t a Kyle Lonnergan in my class. I’m not even sure who that is. Why did I mention him?”

The Doctor leaned forward and looked at the register, confirming that nobody called Lonnergan was there. Then he looked around at the room and counted thirty-five seats around the tables.

He casually flipped through the stack of exercise books he had carried from the TARDIS, then without saying anything at all he carried them back into the console room again. He emerged from the stationery cupboard just as the students started to come into the classroom. They found their seats, spread around the almost empty tables.

“Who’s he?” asked one of the girls, pointing to The Doctor.

“He’s….” Marie began, only then realising that The Doctor was still there as the day’s lessons were beginning.

“Your boyfriend?” somebody suggested.

“You’re dad?”

“Granddad.”

“I’m your teaching assistant,” The Doctor said with a glare that silenced the whole group. “I’m ‘old school’. I don’t do any of that touchy, feely, understanding your issues sort of thing. Sit down, bags off tables, and shut up so that Miss Reynolds can teach you something.”

Funnily enough, it worked. The room became very quiet and still. Marie scanned the register and did a head count, then handed back essays and collected weekend homework. All of that was done in double quick time leaving a strange empty gap before it was time for assembly. They lined up quickly and quietly and Marie got ready to lead them to the hall. She gave The Doctor a look that said both ‘stay there, I’ll deal with you later’ and ‘Thank you!’ at the same time.

While she was gone, The Doctor looked around the classroom again. There was definitely something wrong. He could practically smell it.

He really COULD smell something. Meisson energy unless he was very much mistaken.

That was odd. Classrooms were supposed to smell of body odour and chalk – or more likely dry wipe markers these days.

It was a familiar smell around Cardiff, with the Rift and the activities of that Torchwood bunch, but Meisson energy didn’t belong in a school in a Dublin suburb.

The assembly was over. The sounds of patent leather shoes on hard-wearing floors thundered along the corridor outside. Other classrooms had their full complement of students by the sound of things.

Ten youngsters came into the room followed by Marie. The Doctor glanced at the register. Ten was the correct number.

He watched Marie set arithmetic problems for her class, then quietly picked up the register and beckoned her towards the stationery cupboard, glad that there were so few students to actually notice. Eleven year olds were knowing enough to make something of a man and woman going into a confined space.

“How many students do you have in your class?” he asked bluntly.

“Ten,” Marie answered right away.

“Correct,” The Doctor said glancing at the register. “For the moment, anyway.”

He picked up the first of the exercise books on the pile that had been in his TARDIS for a week.

“Who is this, then?”

Marie took the slender book with its thin orange-brown cover and opened the pages. She recognised lessons she had taught since the start of the school year. Dates at the top of the pages confirmed when the work was set. She recognised her own handwriting urging more effort from a student called Assumpta Devine.

For a brief moment she thought she knew Assumpta as a pale girl whose blonde hair was tied back in severe pigtails.

Then she lost the memory again. She picked up another book and read another name that she only knew for a mere moment.

She went through all of the exercise books and grasped at mere ghosts of memories.

“What is this?” she asked. “What’s going on?”

“This is the class you’re supposed to be teaching,” The Doctor told her. “A week ago, when you left these books in my TARDIS, because you were in a tizzy about being late to something or other that humans get excited about, you had thirty-five students. Now you have ten.”

“But… no… I don’t….”

“Twenty-five children don’t go missing without a huge uproar. Police, social workers, parents making tearful appeals on television, candlelight vigils. This is not normal. They’re NOT just missing. They’ve been erased from existence.”

“That’s… not possible.”

“You had twelve students this morning when you checked the register. Now you’ve got ten. Two more disappeared during assembly.”

Marie didn’t know what to say.

Except she knew, instinctively, that The Doctor was right.

She didn’t know how. To her conscious mind she had always had ten children in her class. It made no sense having such a big room for just ten. It made no sense employing her to teach so few. They could as easily be incorporated into other classes.

But ten children it was. There they were in the register. The register was correct. It was complete. There were no names crossed out. Nobody was missing.

But then who wrote all those badly spelled essays in those grubby exercise books? Again, she picked up a flimsy volume and looked at the name von the front.

Laurence Bagnall - Labhrás Ó Beigléinn.

Constitutionally, Ireland was a bilingual country. Teachers were meant to turn out children who were confident in English and Irish.

Practically, getting some of them to express an original thought in one language was hard enough.

Laurence had at least learnt to spell his name in both languages. He knew a smattering of phrases, too. Some of them she had told him off for using. They were too rude for translation.

She could remember all of that as she looked at his name on the front of the exercise books.

But when she put it down again the memory faded until all she could remember was that she had forgotten something important.

“Marie… look at the register again,” The Doctor said in a carefully calm voice.

She looked.

Nine names.

“That’s right,” she said. “Nine…”

“It was ten a few minutes ago.”

“No, its nine. It’s always been nine.”

“No, it hasn’t. Marie… think. The TARDIS should be protecting you a little bit, the way it protected the existence of those books. Think about it.”

She thought about it.

Then she gave a cry of horror and ran out of the TARDIS, into the classroom, clutching the register that told such an odd story.

The Doctor followed a little more calmly. He looked around in surprise. She wasn’t there.

“Where did Miss Reynolds go?” he asked the students.

“Who?” one of them asked in return.

“Miss Reynolds. Your….”

He glanced at the register in his hands.

It shouldn’t have been in his hands. It should have ben in Marie’s hands. She had been holding it when she left the TARDIS.

At the top of the printed list was the name of the teacher in charge of these students.

The Doctor!

As the shock of being turned into the custodian of the minds of nine human children died down he noticed something written on the register.

It was in Marie’s handwriting. It was just three words, probably all she could manage before she was erased from existence in this world. Those words almost certainly only survived because of his presence, a being who lived beyond time and space. He was a spoke in the wheel, a grit in the ointment, or some other metaphor, anyway.

He put down the register and strode across the room towards the child who had, incredulously, caused the fabric of reality to become another dangerously unbalanced metaphor.

Marie wasn’t sure where she was. The place was curiously unreal. There was some kind of surface that her feet touched, but a sort of white mist swirled around her shoes. The same mist made it impossible to see whether there were any walls or ceiling or how far either might be. It felt as if it was a room rather than open air, but she didn’t know for certain.

If the location was one mystery then another had, at least been answered, because she wasn’t alone in this mysterious nowhere that she had been suddenly transported to.

And she remembered everything and everyone, now. They were there with her – twenty-six of her students, including Kyle Lonergan who could be bright when he tried and Frankie Gerard who spent too much time going to the toilet to have time to learn anything, as well as blonde, pigtailed Assumpta Devine, Laurence Bagnall who could spell his name in Irish as well as English.

There were other people here, too. Marie recognised some of them. Mrs Brady, the dinner lady, Mr Fahey, the lollipop man, Mr Egan, the school janitor. None of them had been around for days, but she hadn’t realised because each of them were so easily rubbed out of existence.

There was another man she only vaguely recognised. He was dressed in pyjamas and a dressing gown and had a day’s stubble on his face.

“Who are you?” she asked.

“Vince Boyle,” he answered. “I know you. You’re that snip of a woman that teaches our Liam… putting ideas in his head that ‘education’ will do him any good.”

Marie felt instinctively that she didn’t like Mr Boyle.

“You’re Liam’s dad?” Assumpta asked.

“Yeah, what about it?” the surly man snapped.

“I think Liam did this,” the slight, timid child said. “I was just trying to be nice to him. He was hiding around the back of the gym at break time, crying. But he was mad at me for seeing him like that. He was really angry. And then… then I was here.”

“You’re saying my lad did this?” Mr Boyle demanded. Assumpta shrank back from the angry man, but it wasn’t her he was directing his anger at. His declarations of what he planned to do to his son when he got back disturbed everyone.

“I don’t think you’ll do anything of the sort,” Marie said calmly, though the stoutly built Mr Boyle scared her a little. “Not with this many witnesses to your threats. So enough of that, for now. I’m wondering what else might have prompted Liam to take action against so many people.”

Several of the youngsters looked uncomfortable. Marie questioned them sharply and they admitted to bullying Liam for quite some time.

“You know that’s wrong,” she told them. “Completely wrong. Not only is it against school rules, but it’s a vile, horrible thing to do.”

“Don’t even think about it, sunshine,” The Doctor said as he swooped upon Liam Boyle. The message on the register said ‘take his iPhone’. The Doctor grabbed the phone from him and held it firmly. On screen he saw a very small list of names. “Your ‘friends list.’ Not many of them left, now. A couple of aunts you still like, and these eight kids who haven’t annoyed you enough to be deleted. Oh, and me. That’s interesting since you didn’t know me until about half an hour ago.” He looked around at the other children, all looking curiously at the strange drama playing out in their class. “You lot shoot off to the library or something. Call it a free period. Don’t make any trouble for any other teacher.”

There was a quiet but swift withdrawal from the classroom. When they were alone The Doctor turned back to Liam who looked exactly like somebody who had been caught in the act.

“This isn’t just an ordinary phone. Where did you get it?”

“A man gave it to me… just a man in the street.”

“Very generous of him,” The Doctor remarked. “What sort of man?”

Liam shrugged.

“Just a man. He said it would help with my problems. It… doesn’t work as a phone. Or as internet. It just has the ‘friends list’ on it. Except Andrew Sullivan, Michael Doyle and Finn Doherty aren’t my friends. They’ve been hurting me since the first years. They said they’d hurt me more if I told. But… when I deleted them from the list… they weren’t there any more. Instead… Seamus Creaney started picking on me, instead. So I deleted him. Then… my dad… He was in such a mood… and then he was gone. Everyone….”

“I’m afraid I told him off,” Mrs Brady said. “He didn’t like the fish last Friday, and I told him he was ungrateful. It was good food that plenty of children would eat in no time. I didn’t mean to be cross. I just hate to see food wasted.”

Marie had noticed a pattern. After the worst of the bullies, most of the stories had been simple enough. A scolding for running in the corridor, a warning about waiting to cross the road had been enough to incur Liam’s wrath. Other children had done as little as bumping their chair against his in class or accidentally tripping him up in the playground. Some had made the mistake of being kind to him when he just wanted to hide his humiliation and pain.

“So, apart from your dad, and four or five real bullies, nobody really did you any harm?” The Doctor said. “It was all just little things. But you’d got into the habit. Anyone who upset you in the slightest way was deleted.”

Liam nodded. He couldn’t talk for the tight, humiliated lump in his throat.

“Where did you send them?”

He shook his head to indicate that he didn’t know.

“Bring them back. All of them. Especially Miss Reynolds. She never did the slightest harm to you. She has never done anything but help all of you.”

“I can’t,” Liam managed to whisper. “I don’t know how.”

“Bring them BACK,” The Doctor repeated, a little more firmly.

“I can’t.”

“BRING THEM BACK, NOW!” The Doctor shouted. Liam shrank back from him, shielding his face from expected blows.

“Don’t hit me!” Liam cried out.

“Of course I won’t hit you,” The Doctor answered in calmer tones. “I’ve never hit a child in my entire life. And that’s a lot of life. Besides, too many people have hit you already. What would that achieve? But you have to bring them back. You know you must.”

Liam was crying, now, not because The Doctor had been cruel to him, but because he had been kind.

But he still didn’t know how to bring his class and all the other people back.

“Yes, you do,” The Doctor told him. “It’s a friend’s list. You can add to a list as well as delete from it. I was added. Who else could be?”

Marie had found out something else about the strange limbo they were all in. No time passed here. Not only did nobody’s watches work, but the children who had been there for as much as a week weren’t hungry, thirsty or tired. Frankie Gerard hadn’t needed the toilet – which was just as well as there didn’t seem to be one. And nobody had really felt any passage of time since they found themselves on the wrong side of Liam Boyle’s flashpoint anger. It was as if it had only happened moments ago.

It was an interesting aspect of the situation, but she wasn’t entirely certain how it was going to help.

“Miss!” Fiona Creasy raised her hand just as if they were in class. The absurdity of that was enough to make her cry if the importance of what Fiona had to say hadn’t distracted her. “Miss… Assumpta isn’t here.”

“What? No. Don’t anyone wander off. You don’t know what might be out there.…”

She stopped talking and looked at the student group. There definitely were less of them now. They were looking around and mentioning names of friends who had been there a second ago…. Vinnie Scott, Kevin Bagley, Annie Byrne….

Then she blinked and looked around. She was back in her classroom. A dozen of her students were there, sitting in their seats, looking bewildered and a little disbelieving, as if they had been in a dream.

The Doctor was there, standing beside Liam, who was typing quickly on his iPhone. Each time he pressed return, another student came back to where he or she belonged. Her classroom was filling up again.

Soon the only empty chairs belonged to the nine The Doctor had sent to the library.

“What about the adults?” Marie asked. “Mrs Brady, Mr Fahey, Mr Egan… and….”

“They’re all back,” The Doctor said. “In their proper places. Everyone except….”

“I won’t bring him back,” Liam insisted. “I hate him. I hate every day I’m at home with him and his temper. He’s gone… and I’m glad.”

He threw the iPhone across the classroom floor. It exploded with a flash of flame and actinic white light that melted all the plastic parts. Marie finished off the rest with the compulsory classroom fire extinguisher. The Doctor picked up the soggy, melted mess and examined it with his sonic screwdriver.

“I think that’s the end of that,” he said. “No getting anyone else back, now.”

“So... Mr Boyle is gone for good?” Marie wasn’t particularly sorry. Being trapped in an endless nothing was as good as the jail sentence she had been wishing on him for mistreating his son.

Liam wasn’t sorry. In fact, he looked relieved. A hard part of his life was over.

“I’ll call social services,” Marie said.

“No, I’ll do that. I can cut corners with those sort of people and get him looked after properly,” The Doctor promised. “Besides, you’ve got a stack of marking to do, still.”

She went into the TARDIS to collect the exercise books.

There was something else she had to talk to him about. The TARDIS seemed the place for it.

“Doctor… there’s something I was thinking about when we were… wherever we were.”

“Yes?”

“I was thinking that… some of this was my fault.”

“It wasn’t. I detect the work of a character called The Trickster. I think he gave the phone to Liam. Don’t worry. He’s old news. I’ll deal with him later.”

“Ok. But… every weekend I’m away with you doing great stuff. And until about Wednesday I’m thinking about what we did. Then the rest of the week I’m looking forward to what we WILL do when you take me away again. And I’m just marking time until the Friday bell rings. I’m not giving those kids the time I should be giving them. I should have known Liam had problems at home. I should have spotted the bullies having a go at him. I should even be able to deal with Gerard’s toilet problems. Lord knows, somebody should. I need to concentrate on my job.”

“Does that mean….”

“It means… incredible as it may seem… that I can’t go off with you every week. It… means… goodbye.”

“For good?” The Doctor asked. What he felt about this sudden turn of events she wasn’t entirely sure. Was he sorry? Was he glad to be rid of her?

“Maybe… THIS Friday, just to round things off… you can take me to that fantastic space restaurant with the name after a Greek letter I can never remember. Just to say a proper goodbye. And then… after that… Come and check up on me when I’m sixty-four… like in the Beatles song. If I’m not married to some great bloke and got a couple of grandkids and plans to retire to a cottage in Wicklow… then you can take me back to Inisfree… the planet, not the island. I’ll keep my hand in with the spinning and weaving and home made breadmaking and I’ll be grand retiring to a little cottage THERE.”

“You really HAVE thought it through, haven’t you,” The Doctor said.

“No time passed in that weird place. But I got through a lot of thinking, all the same.”

“All right. Friday it is… for a slap up goodbye meal at the Omicron Psi Orbital restaurant. And if you haven’t changed your mind, by then….”

“I won’t have changed my mind.”

“I always give women two chances.”

“Go on. Get off with you now. Let me get back to my class before they riot.”

She picked up the exercise books and turned to the door. She stepped into the stationery cupboard, then into the classroom. She heard the sound of the TARDIS dematerialising and felt just a slight twinge of regret about her decision.

The Doctor felt a twinge of regret, too. But he had a universe beyond the TARDIS threshold and billions of people to meet. One, two, perhaps three, among them, might be worth inviting aboard the TARDIS for a while.