“How do you feel about Wales?” The Doctor asked Marie as she stepped aboard the TARDIS.

“The animals or the country?”

“The country.”

“In that case, mostly friendly except when rugby internationals are on. Why?”

“I’m picking up some temporal anomalies in a Welsh valley. Could be nothing. We might just have a picnic in the sunshine. Could be something that Torchwood lot should have spotted. We’ll beat them to it.”

“Well, green monsters in Wales aren’t likely, I suppose.”

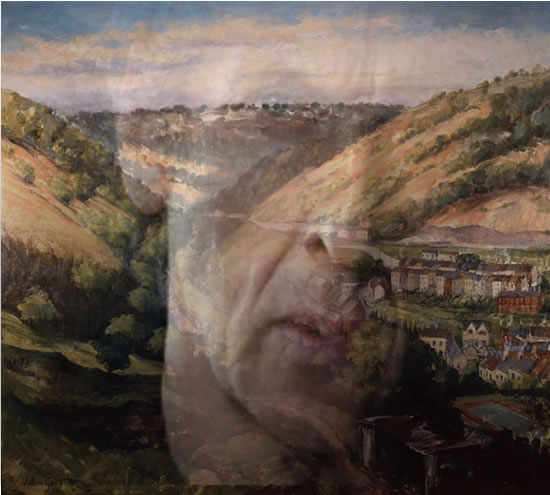

“I’ll tell you a story some time.” The Doctor grinned wickedly as he set their course. “Llanbach valley. One of those former mining communities turned dormitory village for Cardiff commuters. Two pubs, one church, one Spar shop with a sub-post office the government hasn’t managed to shut down, yet.”

“Sounds bleak,” Marie commented. “Why do you suppose there are ‘temporal anomalies’ there?”

“Lots of reasons. The way most of south Wales was carved out by the coal industry… it left pockets of emptiness that get filled in by more than just stale air. Plus, Cardiff has a rift in time and space running through it. Anywhere in the hinterland you get eldritch and strange things happening every day. The Torchwood lot spend most of their time erasing people’s memories and covering up the mess.”

“That’s the second time you’ve mentioned Torchwood. Who are they?”

“Trouble, usually. We’re not getting involved with them.”

Marie was inclined to question him further, but there was a distinct ‘subject closed’ tone in his voice. Instead she went to change her shoes to something practical for Welsh valleys.

She got back to the console room just in time for it to tip sideways giving the floor a gradient comparable to a Welsh valley. She grabbed a handhold and flattened herself against the bulkhead until normality resumed.

“What happened?” she demanded when she finally reached The Doctor’s side.

“We bounced off the temporal anomaly,” he answered. “It won’t let us into the valley by TARDIS. We’ll have to walk.”

“Ok. As long as it isn’t raining.”

It wasn’t. In fact, it was a very pleasant spring morning, which struck Marie as odd since she had left Dublin on a cloudy afternoon in late September.

But, after all… TARDIS travel!

They followed a well-made two-lane road for a little while. There was a gentle slope upwards on the left, dotted with sheep, and a steep one down to a small river on the other. The land on the other side – again dotted with sheep, rose upwards again. A line of trees blocked the view further upriver.

A few cars went by from time to time. The two walkers obeyed the old rule of facing oncoming traffic when there was no footpath.

It was a pleasant walk, even though The Doctor spent the time actually telling her why green monsters and Wales were not so absurd after all.

“Ugggh. Really? Giant maggots? I think I’d be having the heeby-jeebies at the sight of them.”

“Young Jo did a very good job of hiding her heeby-jeebies,” The Doctor said with a note of pride in his former companion. “Anyway, Llanfairfeach is about twenty miles thataway, nothing to do with Llanbach.”

“Llanbach literally means ‘little town’,” Marie pointed out.

“Does what it says on the tin,” The Doctor told her.

“Yes… but aren’t they all ‘little towns?’ There could be a hundred valleys with a Llanbach in them. It’s like Bhaile beag in Ireland. There’s at least one in every county, plus a fictional one invented by Brian Friel for his plays.”

“We didn’t have little towns on Gallifrey,” The Doctor noted with a tone that might almost be regret at the lack of rural life on his home planet.

While she was thinking about that she didn’t notice that the valley had started to look different. Exactly how different took a few minutes to fully set in once she paid attention.

“The road doesn’t look quite so good here,” Marie pointed out. “It’s hardly wide enough for two cars to pass, and the surface is really rough.”

“That does happen in the countryside,” The Doctor explained. “We probably came to the border between two local councils who couldn’t decide to continue the road improvements.”

“Could be,” Marie agreed. “I come from the land of potholes. I can’t really complain.”

But it wasn’t the only thing that looked wrong.

“The coal mine,” she said, indicating the grey feature against the blue sky and green fields. “The pithead… with the wheel for raising the lift… they stopped using those sort in the seventies. And most of the modern pits were closed down in the eighties… you know, Thatcher. And don’t tell me that’s some kind of museum or heritage thing, because shutting down the mines hurt communities like this. They’d burn down a ‘heritage museum’ based on a way of life snatched from under them.”

The Doctor said nothing. Marie looked carefully at details she might have missed if an idea hadn’t been forming in her mind.

As they passed a row of cottages with garden fronts she noticed that every one of them had a line of washing hung up to dry. That struck her as more than a little old-fashioned. Most people she knew had tumble dryers, and even if they didn’t the idea of a ‘washday’ when every housewife did the same job at the same time was long gone.

Kneeling down to scrub the doorstep with a hand-held brush was a lost art, too. It belonged in nostalgic black and white photographs that pre-dated labour-saving devices and Women’s Lib.

But they walked past a whole row of terraced houses where women were doing just that.

Marie finally decided to take The Doctor to task as they came to the village shop-cum-post-office. Any number of things about that shop struck her as wrong. There were adverts on the walls for products that hadn’t been manufactured for at least fifty years, prices in ‘old money’ and the general style of the shop with almost everything for sale behind a long counter, most of it in large jars to be weighed on scales and put into paper bags. No self-service, no pre-packed goods except for carbolic soap and bleach.

Marie watched a boy of about eight years old go into the shop. He was wearing shorts only a little longer than his duffle coat with grey ankle socks and sturdy shoes. She noticed that he bought some sweets and an ounce of tobacco in near identical paper bags.

“You don’t see that every day,” Marie commented. “Not in MY day, anyway. Doctor… you realise we’re not in the right decade.”

“I do realise that,” he answered. “I think we passed through an interstitial gap just about when the road quality changed. I didn’t want to worry you.”

“Didn’t want….” Marie started to say something, then changed her mind and started to say something else.

Then she gave up and glared at The Doctor disapprovingly. It didn’t really work. The glare was deflected by his eyebrows.

Then she looked around again at a scene she would never have believed was real. A boy was huffing up the steep cobbled street with a bike fitted with a huge wicker basket. An actual baker’s boy. She didn’t have Dvorak’s New World Symphony as an earworm, but that was because she was Irish and grew up with different bread adverts on her TV, but she understood the cultural allusion all the same.

The Doctor had gone into the shop. He returned with a quarter of aniseed balls and a newspaper. He showed Marie the date.

April 18th, 1932.

It seemed like a very ordinary day. No wars had started, no assassinations, nothing to worry anyone. The economy was rocky, post Wall Street Crash, but when wasn’t it for people in little places like this?

“Can I look around?” Marie asked. “I know you have to look for temporal anomalies, but I’d rather go and have a look over there.”

The focus of her attention was the village school. There were children gathered in the playground before the start of the school day and a few latecomers hurrying along. She noticed the little boy who had bought the sweets and tobacco. He gave the latter to a man in a dark suit who stood by the school gate. He had been running an errand for his school master – buying him tobacco. That really was a sign of times past. At her school, teachers were specifically banned from smoking until they had driven well away from the school gates.

The master put the tobacco in his pocket and stepped through the gate. He rang a bell and the school children lined up to be led inside.

Marie followed them. She waited in the vestibule as the children assembled in the larger of the two classrooms for hymns and prayers led by the same master.

“Hello…” A woman about her age came out of the other room and addressed Marie. “May I help you?”

“I’m Marie Reynolds, from Dublin. I’m visiting your town,” Marie explained. “I’m a teacher myself. I was wondering if I could see how things are in a small school like this. I’m used to a big city one.”

“Come on into the infant’s room. I’m Ruth Evans. I look after the little ones. Mr Griffiths takes the older children who are working towards their school certificate.”

The room was not as bright and jolly as the infant’s class at the school she worked in, but the small desks and the alphabet charts were familiar enough.

There were some maps on the wall. They intrigued Marie. One of them was a map of the British Isles. Somebody had very carefully drawn over the border between England and Wales in thick black ink so that there was no doubt about where it was.

They had also amended the map of Ireland. The border between Northern Ireland and The Irish Free State had been painted out and the whole island coloured green, while ‘Irish Free State’ was crossed out and replaced with ‘Irish Republic.’

Marie looked at Ruth. She smiled apologetically.

“Mr Griffiths is a nationalist,” she said. “He was very angry about Irish partition and the refusal to allow the Republic, and he dreams of an independent Wales, too.”

“I hope there are clean maps for when the school inspector visits,” Marie said.

“There are,” Ruth confirmed. “Though what would happen if the Inspector asked any geography questions, I shudder to think.” She listened to the sound of a Welsh hymn coming to an end followed by the scrape of chairs. “Assembly is over. The children will be coming in, soon. We’re doing arithmetic, first. Then it’s reading.”

The children came in far more quietly than any class Marie had ever taught. There were at least fifty of them in the lower class of this two-roomed village school. All of them were clean faced and looked neat and tidy with shirts tucked into shorts and smock blouses ironed. Socks were pulled up, shoes as clean as they could be after walking to school on unpaved roads.

They stood by their desks and waited to be introduced to Miss Reynolds who was visiting their school today. The children chorused a ‘Hello Miss Reynolds’ before sitting at their desks and beginning their lessons.

Marie thought of her own class and how long it took them to put away bags, spit out chewing gum, switch off mobile phones and stop talking about what was on TV last night before she could start to teach them anything.

It was so much simpler here. The youngest pupils at the front settled down to a series of simple sums copied from the blackboard onto slates. Ruth made sure every three or four sums were correct before they scrubbed them out and moved on to the next three.

The older ones at the back were memorising multiplication tables, their lips moving soundlessly as they traced the figures on the graph in front of them. In between were a dozen girls who shared three text books with practical sums involving weights, measures and prices in pounds, shillings and pence.

Marie hoped none of them asked her for help. She didn’t know how to add up money in pounds, shillings and pence. It was well before her time.

It struck her as significant that it was all girls doing these practical maths problems, the sort needed for buying groceries. This was not a time when there was any sense of equality in education either for class or gender. These girls were going to grow up to be wives to a new generation of coal miners. They would hang washing on lines and scrub doorsteps with a pride in their homes instilled by their mothers, buy groceries, make meals for their husbands and children.

They weren’t expected to go to secondary school, let alone college or university. Even learning typing and being the colliery secretary was probably an out of reach dream for them.

Yet it wasn’t so depressing as it sounded. These girls knew what their future held. They weren’t worried about exam results, about having their dreams crushed for being a few points short of a quota. They knew where they were going even if it wasn’t very far.

They were happier than a lot of the children she taught, with all those anxieties already heaped on their shoulders.

Of course, Marie also noted, there were going to be changes. There would be war by the time these girls were grown up. Coal mining was an ‘exempted service’ meaning that men from the pits weren’t called up to fight. Life in these valleys might not be as badly disrupted as it was in other places, but they would all still have a hard few years ahead.

But they didn’t know that, and they were happy.

The Doctor was less sure about where to begin his exploration of the village. In a community of coal miners just WHO might be causing a temporal anomaly that had stopped the TARDIS from entering the valley but opened an interstitial gap that he and Marie had passed through on foot?

There had to be a reason why the gap opened on this time.

But there were no scientific institutions here, no university facilities. It couldn’t be that simple.

It was probably going to be some scientist working on his own in the basement of his house.

You know, like Uncle Quentin in those Famous Five stories. The Doctor smiled wryly as he thought about that kind of archetypal eccentric professor with horn rimmed glasses and so many ideas his human brain couldn’t contain them all.

They were the people who would, eventually, let the human race stand as equals alongside the naturally great races like the Time Lords.

Eventually.

In the meantime, they tended to be a thorn in his side, inventing things humans weren’t ready for, like matter transmitters and shrink rays. Usually he would have to come in and sort out the mess when the experiments went awry.

And he was ready to bet that was what was happening here, today.

But where to find the eccentric professor of Llanbach? Where to even start looking?

After morning break, Ruth’s class had Reading, the only genuine ‘R’ in the Three ‘R’s. There was a small library of books in the back of the class, mostly collections of short stories with moral lessons to be learnt from them or true stories of heroism and adventure like Captain Scott or Grace Darling.

There were also, Marie noticed, quite a few stories about Welsh heroes such as Llewellyn the Last and Owen Glendower. She wondered if those were put away when the school inspectors came around, as well as the nationalist maps.

The Doctor found the local chapel, but there was nobody there on a weekday morning except an elderly cleaner. He found the pub, but that was closed until the men came off the day shift at the colliery.

Then he found a day centre for retired miners where he enjoyed a cup of tea and a slice of something called Welsh Cake – a sort of flat scone - with men whose eyebrows were as fearsome as his own. They all had leathery complexions and hands tattooed by coal dust worked under the skin over decades of labour.

The old men were happy to talk about any subject under the sun as long as it worked back around to chapel, choral music or rugby. These were not just clichés about Welsh people. They were their genuine preoccupations.

The Doctor wasn’t sure, when he thought back on the conversation, which thread brought him to the subject of Cadoc Bledynn, but eventually it did.

“Professor Bledynn he is, properly,” said Evans the Old, the most grizzled and leathery of the old men. His son, Evans the Young, was also a member of the club. His grandson was a foreman at the colliery and was known as Evans the Daughter because his only child broke the chain of mine workers and became a teacher. “But mostly he’s known as Bledynn the Smoke. Always something burning in his ‘laboratory’, funny old smells, different coloured smoke some of the time.”

“He’s all right, of course,” added Thomas the Red – for his ginger hair not any political allegiance. “But he moved here from the city. Said he wanted the peace and quiet – and something about the hills. But whoever heard of a scientist in a place like Llanbach?”

“He comes to chapel,” Burton the Winch, for his former job at the colliery, added. “He’s usually late. He says he forgets the day of the week until he hears the bells ringing, and by then he has too far to walk. He usually misses the first hymn.”

The Doctor got directions to the professor’s house, far enough outside the town to be late for Chapel every weekend. He drank more tea and then bid goodbye to men with eyebrows even more fearsome than his own and set off to find Bledynn the Smoke.

At lunchtime, Marie shared Ruth’s bread and cheese and a strong cup of tea. Afterwards she went to the upper classroom where Mr Owen Griffith was delighted to share his educational views with her.

“We’ve four students taking the higher certificate,” he said proudly. “They’ll be going on to the grammar school in Abergavenny. There’s a special fund for the children of miners who get the best exam results. Four of them from our little school….”

“Wonderful,” Marie agreed.

“You speak very good Welsh,” Mr Griffith told her. Marie was startled by that. She hadn’t even thought about it. The TARDIS translation circuits turned everything she saw or heard into her first language – English. She hadn’t even realised that the books in the junior class library were in Welsh, or that Ruth had been teaching maths through the medium of Welsh.

Mr Griffith then spoke to her in Irish. It came out in English, but with a different idiom that alerted her.

“You speak very good Irish,” she told him, in Irish, but sounding like English when the words came out of her mouth.

“I have spent many summers in Connemara,” he told her. “Learning the native language of your country that the British Imperialist Machine tried to crush.”

Marie replied vaguely. Yes, the Irish language, and Welsh and Scot Gaelic had suffered under British rule. But it had to be said that, in her time, after nearly a hundred years of self-rule, there were no more native Irish speakers than there were under the British Imperialist Machine. She thought Mr Griffith would be very upset if he knew that. He had high hopes for self-determination of every national colour.

The end of the lunch break curtailed the political discussion. Marie sat at the front of the class and watched Mr Griffith teaching history as laid down in the curriculum set somewhere in London. It was British history with an imperialist slant, but at any possible opportunity Mr Griffith found ways of emphasising Welsh achievement. She noticed that one of the visual aids on the wall was a print of a painting of the Defence of Rourke’s Drift, 1879. Marie was fully aware of the contradiction. Yes, Welshman were valiant – but their valour was for the British Imperialist cause. There were similar painting of the Irish regiments at the Somme that fitted awkwardly alongside national pride.

She noticed that the four potential grammar school children were set different lessons that they quietly got on with on their own. She looked at what they were doing and noticed that their text books were most certainly printed in English. This time it wasn’t the TARDIS translating.

Of course, for anything more than a basic education they needed to take exams in English. It was like that in Ireland, too, in these days. That was what frustrated the language movement in either country most of the time.

At the same desk, with the same books, was a girl. She was neatly dressed in a smock and blouse in contrast to the boys’ school clothes. Her hair was plaited and fixed on top of her head so that it didn’t interfere with her work as she bent over her exercise book and wrote an essay about industrial advances in the Victorian era. She looked up politely as Marie stood next to her and said her name was Alice Jenkins.

“Yes, Miss,” she said in answer to Marie’s enquiry. “I hope I can go to the girls’ grammar school. My da is saving for the uniform and to pay for me to stay at a boarding house in Abergavenny during the week.”

“I heard there was a fund.”

“It’s only for boys,” she answered. “I suppose they never expected a girl to want to go to grammar school. Anyway, da says he’ll find the money himself, without help from any charity.”

“Good for your da,” Marie told her. “What do you think you’d like to do when you’re older?”

“I want to be a chemist,” Alice answered straight away. “Not in a shop, making up medicines, like Mr Abott, but at the university in Cardiff, inventing new medicines. I know I will have to work very hard to do that. And I will have to leave Llanbach and only come back to visit. And ma says girls who do that sort of work aren’t able to get married and have children, but I don’t think I’ll mind that.”

“You go for it,” Marie said. “Don’t let anyone stop you. I’ll look in twenty years to see if you’ve invented anything.”

“Thank you, Miss,” she said before getting back to her essay.

The Doctor recognised the cottage by the green-yellow smoke rising from a metal chimney fixed to the gable wall. There was a smell that he identified as four different chemicals – all quite inert when left alone but producing explosive results when brought together.

He recognised Caddoc Bledynn by the fact that he had no eyebrows at all. His fingers were stained by chemical compounds as was his lab coat.

“I’m The Doctor,” he announced to the Professor. “I’ve heard a lot about your work. May I see over your laboratory?”

Any scientist working alone would usually become very defensive and proprietorial about his experiments. Even Uncle Quentin was like that. But a little Power of Suggestion and perhaps superior eyebrows did the trick. Bledynn the Smoke invited him in.

“I heard about your experiments,” he said just to keep up the casual but pertinent conversation as Bledynn brought him through the cottage to the room he had made into his laboratory. It was an extension at the back of the original building and all four walls were solid Welsh stone. It was probably what stopped the room from disintegrating. Some suspicious colours staining the walls were testament to the strain they were under on a regular basis.

“I am surprised,” Bledynn said in answer to that. “My colleagues in the profession are usually quite dismissive of my ideas. That is why I prefer to work alone. Besides, the mineral rich mountains enclosing this valley give me protection from radio waves. They are quite a nuisance, these days, and I hear there are experiments with television, too. Where will it end.”

“Where, indeed,” The Doctor remarked casually. He played the Professor’s words back twice in his head, trying to find a way to justify their absurdity. Reluctantly he found the word ‘crackpot’ settling in his mind.

“But my latest work is in quite another direction altogether. Let me show you….”

He directed The Doctor to a curious contraption in cast iron and rudimentary electronic components that looked like an extra-large sandwich toaster for a very hungry Slitheen. It was obviously the source of the strange smoke and most recent wall stains.

He tried to find a way of asking what it does without actually saying ‘what does it do?’

Fortunately, Bledynn was quite forthcoming.

“I am, as you see, very close to finding a way of turning common carbon – coal, that most abundant substance in these hills – into diamonds. The combination of extreme pressure and heat performs that amazing metamorphosis. I have, unfortunately, had some difficulties with the precise formula, but it is only a matter of time.”

“Yes, of course,” The Doctor commented. “The theory is perfectly sound. Coal and diamonds are the same substance in two different forms.”

“Think of it. The miners of this valley working all hours for so very little money… imagine if they were able to mine the raw materials of diamonds.”

“They mine coal by the tonne,” The Doctor pointed out. “Do you intend to make it all into diamonds? Surely you would flood the market and devalue the diamonds until they are worth no more than coal?”

Bledynn looked at him as if he was speaking a foreign language. He might be a brilliant, if impractical, scientist, but he was certainly no economist.

And he was clearly not a person who was likely to cause a temporal anomaly. He might blow himself into next week, but only metaphorically.

The Doctor wasn’t sure whether he was relieved or disappointed. On the whole, perhaps, the former. He had found himself liking the clearly deluded but harmless professor and discovering that he was at the heart of something dangerous would have been sad.

But if it wasn’t him, then he was right back at square one, with no clue about the source of the temporal anomaly.

After a cup of tea and some scientific gossip, he walked slowly back into town, wondering what he ought to do next. He felt quite at a loss, and that was a rare enough thing for him to be disturbed by it.

He reached the little village shop just as Marie emerged from the school opposite. She waved cheerfully to several of the children as they rushed out of the school gate and ran home. She came to him smiling happily.

“I had the best day,” she said. “I wish teaching my lot was as pleasant. Those kids barely have enough books. They have two classrooms, two teachers between the lot of them, and they’re so eager to learn, valuing every moment. Modern kids waste the opportunities they have.”

“These ones run home just as quickly as yours,” The Doctor pointed out. “They value their freedom from school just as much. Anyway, are you ready to say goodbye to Llanbach?”

“Not really, but I suppose we must. We have to find the TARDIS.”

“I just hope we can,” The Doctor remarked as they set off together.

“What do you mean?”

“Interstitial doors don’t always go both ways. We left the TARDIS in a time we may not just be able to walk back into.”

“And you didn’t think to tell me that earlier?”

“You were enjoying yourself so much. I didn’t want to worry you.”

“Will you stop trying not to worry me and tell me the truth about our situation,” Marie said crossly. “I really would rather be aware of these things.”

“Duly noted,” The Doctor replied, though that wasn’t, actually, any undertaking to change his attitude in future. Marie walked on, still liking the countryside around her, but wondering what would happen if they were stuck in it. Could she resign herself to life in the nineteen-thirties? What about everything she took for granted, from WiFi to indoor toilets? What about that war only seven years away?

What about being around to see if young Alice got her wish to be one of the few female chemistry graduates of her era, whether she would become a noted scientist or the infamous Llanbach poisoner with her knowledge of chemicals and a grudge against those holding her back.

She crossed the line between the nineteen-thirties road and the better one from the twenty-first century thinking positively about settling in the valley and was actually a tiny bit disappointed to see the TARDIS.

Then she became intrigued by the car parked next to the TARDIS and the man who stood by it, waiting. He approached them and addressed The Doctor by his chosen title.

“It is you, isn’t it?” the man said in an eager tone. “I saw the police box….”

“You know,” The Doctor told him. “It is quite possible that The Doctor has regenerated into a young woman and I am her travelling companion.”

The young man looked at Marie then back at The Doctor after a moment’s indecision.

“No, sir. I have all of your known identities on record. I’m….”

“Don’t tell me, Torchwood?” The Doctor said wryly.

“No, not exactly,” replied the man who hurriedly introduced himself as Garroid Williams from Merthyr Tydfil. “Torchwood really only exists in name these days. I have been keeping an eye on people who go into Llanbach Valley. Most of them pass straight through on the new road, but occasionally there are people who are ever so slightly time sensitive... people who’ve lived near the Cardiff Bay Rift, for example... who need looking after.”

“Looking after?” Marie queried, thinking that the phrase sounded like a euphemism from something directed by Quentin Tarantino.

“Usually a short-term memory modification,” Williams explained. The Doctor made a noise in his throat that fully conveyed the warning ‘Don’t try that on us, Sonny.’ Williams quickly moved in.

“You were a huge spike on the scanner... All that Artron energy. I suppose you found the village on a pleasant, quiet day in 1932?”

“Yes.... “

“That’s what everyone with any time sensitivity finds. Everyone else finds an empty valley and wonders why the name means ‘little town' when there isn’t a town there. “

“What do you mean, there isn’t a town there?” Marie demanded. “It WAS there. We saw it. We talked to people. “

“What happened?” The Doctor demanded coldly. “And who's fault was it?”

“Nobody's fault,” Williams insisted. “Nobody has any idea why it happened. Torchwood worked on it for decades. All they know is that there was a massive time surge in the valley. It was the morning of December the eleventh, nineteen-thirty-six. Just after nine o’clock. Everyone in the village died by instant aging. Even the skeletons turned to dust. The buildings collapsed. Within a few years there was nothing to show that anyone ever lived there. At the time, a story was put out about a smallpox epidemic. The valley was quarantined. Later, even that story was quietly erased. The town was forgotten. It didn’t even appear on any post-war Ordnance Survey maps.”

The Doctor gently squeezed Marie’s hand. She held in her feelings until he had peremptorily dismissed Williams and brought her inside the TARDIS.

He let her cry for a few minutes while he looked carefully at the environmental console. When she was capable of coherent speech he listened with as much sympathy as his usual sociopathic detachment allowed.

“All of them died. Ruth, Griffith and his nationalist fervour... All the children... Alice working hard to be an academic when working class girls were at the bottom of the pile.... They all died a little while after we visited them.”

The Doctor nodded. Sociopathic detachment didn’t work when he had eaten Welsh cake with a bunch of old men with eyebrows that could gang up on him or listened to the mad but harmless ambitions of Bledynn the Smoke.

He felt exactly what Marie was feeling.

“They WOULD all be dead of old age by your own time,” he reminded her, knowing it would be no comfort at all.

“But at least they would have had the chance... even the girls who were just going to marry young miners and have babies, scrub doorsteps.... They had the right to do that.”

“I don’t want to give you false hope,” he said slowly.

“What hope?” Marie demanded.

“All that Artron energy left a trail the TARDIS can follow. We can go back to Llanbach with her, now. And we know the date.... “

“December the eleventh, nineteen-thirty-six,” Marie said.

“Total coincidence, but that was the day after the Abdication. I expect that helped Torchwood to cover everything up. Nobody was looking at small Welsh valleys that day.”

“What can we do, though?” Marie asked.

“It’s more what the TARDIS can do,” The Doctor answered. “Look.”

Marie looked at the viewscreen. She saw the sloping cobbled street where a different baker's boy pushed the same bike uphill. She saw Ruth, a little older, going through the school gate along with a gaggle of eager youngsters. She saw Griffith ringing the bell and hurrying up the stragglers.

She didn’t see Alice. By now she ought to be at the grammar school in Abergavenny if everything had gone well.

Everything was the same, everything was a little different. Everything was normal.

She looked at The Doctor. He was watching the dials on the environmental monitor carefully.

“Come and stand next to me,” he said to her in a carefully calm voice. “Give me one hand. Put the other on the console. Don’t let go of either. We’re old enough to give you a protective shield.”

“A shield against what?” she asked. The Doctor didn’t answer. He opened the TARDIS doors and flipped three levers with his free hand while gripping Marie’s slightly nervous and trembling hand tightly.

As the local time showed two minutes past nine there was a crashing noise like a sudden thunderstorm. The sky turned several shades of actinic green, orange and sickly purple. A wind so violent it deserved a better word than merely ‘wind’ whipped around the street.

The wind, the noise and the light were all sucked into the TARDIS. Marie thought, suddenly, about the scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark where all the Nazis melted. She closed her eyes and hoped that was just a stray thought.

Since she had her eyes closed she missed the quite spectacular display of light and electricity arcing around the time rotor as the strange hyper-natural force of the time surge was sucked into it.

She opened her eyes a few minutes later. The console room was quiet. The time rotor was glowing a bit more brightly than usual, but nothing more had happened.

“The TARDIS attracted and absorbed the time surge… a bit like a lightning conductor…”

“A bit like that, but not much,” The Doctor answered. “Anyway….”

He stood at the TARDIS door and watched Evans the Old and his son make their way to the retired miner’s centre. Both pairs of eyebrows were intact.

“They’re all alive?” Marie came to the door and watched a little boy who was VERY late try to sneak into school as a chorus of ‘Bread of Heaven’ rose from the assembly hall. She wondered if he would get past Griffiths’ eagle eye. But even if he didn’t the punishment would not be so terrible as being dead right now.

The Doctor closed the door and went to make a small adjustment at the drive control, then he opened the door again and took Marie’s hand as they stepped outside.

It was still Llanbach, but the cobbles had been replaced by smooth asphalt. There were modern cars passing by.

The school wasn’t a school any more. It was an art gallery specialising in works by local artists who painted or drew scenes from the town and the surrounding valley.

It had a small café. The Doctor ordered lattes and Welsh cakes while Marie did some intensive Googling on her smartphone.

“I found Alice,” she said happily. “There’s a blog about her. One of those family history pages. She went to Aberystwyth university in the end. On a scholarship for the DAUGHTERS of coal miners. She went on to do important research into diseases of the lung… especially those affecting people who live in mining valleys. She also got married and had children and still kept up her career despite a load of antediluvian nonsense about married women in professions. She died last year at the age of ninety-six.”

“What about Caddoc Bledynn?” The Doctor asked.

“He’s got his own Wikipedia page,” Marie said after a few minutes of searching. “It’s not huge, but somebody made the effort. Apparently during the war, he helped develop a radar system that could work in mountainous areas where the regular systems had blind spots. It helped protect the mining valleys from being targeted by bombers. It almost certainly saved many pitheads from being destroyed and thousands of miners from being killed.”

“Good man,” The Doctor said with a satisfied smile. “Does it mention if he ever speculated on the diamond market?”

“No. Why?”

“No reason. We changed history. We’re really not meant to do that. In any other circumstances we probably couldn’t. But Llanbach… didn’t deserve to die. That was why it was trapped in a time bubble, never moving on from the nineteen-thirties. When that was removed, causality had to make room. The threads of time were re-woven around all those lost souls that were found again.”

“Good,” Marie said and sipped her latte with the satisfied feeling of a job well done.

|

|

|