Marie Reynolds watched a woman drop coins into the fountain by the escalator and a child attempt to retrieve them before a parent slapped his hands and dragged him away, threatening to tell the faeries about his attempted theft of their silver.

She smiled wryly. It wasn’t an official wishing well. The money wasn’t designated for charity as it was in some places and since the shopping centre and its fountains weren’t built until 1990 the faeries had no ancient claim over the booty. She couldn’t even see how it could be judged as a criminal act to take the money. It was just one of the more charming traits of her race that when they saw a fountain, a reflecting pool, or even a bit of a stream with a little wooden bridge over it they tended to throw coins in them.

“Where are we?” asked a familiar voice that she had been expecting for the past twenty minutes or so. She wondered if meeting him somewhere so public was a good idea. He was just the sort to start rummaging in the fountain for change or… worse… dropping some weird alien currency in the water just to cause confusion.

“We’re in The Square,” Marie answered patiently, knowing that this was the start of one of those daft conversations she sometimes had with The Doctor and that she needed all her mental energy to keep up. “Yes, I know it isn’t square. It’s more like an unequal quadrilateral. I’ve done that conversation with the kids at school, so don’t you start. It’s called The Square. It was the biggest shopping centre in Europe for a little while – before somebody built a bigger one in Madrid or Manchester or Venice or some other place.”

That was how he usually talked, but she was IRISH and even if it was a cliché that her nation had the gift of the gab she wasn’t going to have an alien usurp them from that position as easily as The Square had been usurped as the biggest lump of concrete and glass in Europe.

“Yes, but what planet or country are we in?” he persisted.

“Ireland,” she replied. “Obviously. Where else do you expect to meet me? I live in Ireland. Come on, you’re buying me lunch before we go off to weird and exotic places. I’m in the mood for something plain and simple and Irish to eat.”

That was easier said than done, she had to admit. Granted KFC and Burger King both firmly assured customers that their chickens and cows were all sourced within Ireland, but that was just a throwback to the last Mad Cow scare over in the UK. Harry Ramsden’s Fish and Chip restaurant also had a buy local policy, even if the chain started in Yorkshire.

She settled for O’Brien’s sandwich bar, one of the few international food franchises that actually started in Ireland.

“This is what I mean,” The Doctor pointed out as he dipped his ham and cheese baguette into a bowl of freshly made cream of tomato and basil soup. “How do you know you’re in Ireland surrounded by PC World, Argos, Carphone Warehouse, Boots….”

He had a point, of course. Generic stores in identikit shopping centres that might be anywhere in Europe were a symptom of modern life that would have upset the founders of Irish independence with their dreams of national self-sufficiency.

“It’s to teach tourists a valuable lesson,” she answered. “They come to Ireland expecting it to be just as it looked when John Wayne was chasing Maureen O’Hara over muddy fields in Galway. They expect all our houses to be thatched and the women to be sitting outside with a spinning wheel as the sun sets over the bay. Instead we give them fast food, mobile phones and internet cafes to remind them that we’re in the twenty-first century, too.”

“Excellent answer,” The Doctor told her. “I couldn’t have come up with a better one myself. Do you KNOW how to use a spinning wheel?”

“No, but I do know how to say several rude things in Irish so as not to upset delicate ears,” Marie answered. “And since your ears aren’t delicate and you allegedly speak five million languages you’ll know exactly what I mean.”

The Doctor grinned. Marie’s sharp Dublin wit was fully equal to his own.

“So what about the coins thrown in bodies of water that are definitely not wishing wells, then?” he countered. Marie smiled. Funny he should have honed in on the very same point she had been making to herself.

“We may be in the twenty-first century, but we’re still Irish. We don’t want to take a chance on upsetting the little people.”

“Absolutely the right answer,” The Doctor assured her. He leaned back and looked out of the window onto the car park and an office block with, in the far corner, just a hint of breathtakingly lovely hills that lay beyond the urban sprawl. “You know, I remember when all of this was fields.”

“So do I. They only built the centre in 1990,” Marie reminded him. “When were you here, anyway, apart from picking me up from school?”

It was probably a bad question to ask, but she knew she had to ask it.

“Oh, around 1730 when the Earl of Rosse presided over the Hellfire Club up on Montpelier Hill,” came the impossible answer. “Those dudes could drink! I remember one night I brought a flagon of Epsilon Eridani brandy. It has all the usual effects of alcohol yet actually IMPROVES cognitive brain functions. There were some really intelligent ideas thought up that night. Unfortunately, when they sobered up in the morning everything was forgotten. That’s the trouble with Epsilon Eridani brandy. You have to keep drinking it until you’ve written your ideas down. Unfortunately, most of the really great thinkers of Epsilon Eridani die young of liver failure.”

“That’s actually rather sad,” Marie told him. “And I would really like you to change the subject, now.”

The Doctor might have been about to do that, but they were both distracted by a sudden commotion. People were screaming and running towards the exits, falling over each other to get off the escalators and tripping over abandoned shopping trollies. A fire alarm rang out over it all and a security guard tried to tell people to exit the building in an orderly and calm manner.

“Too late for that,” Marie noted as she rushed after The Doctor. He, of course, was running in the opposite direction – towards the source of the trouble. Marie had already experienced this several times in her acquaintance with him. She followed despite a strong instinct to go with the ordinary fleeing people who wanted to escape from danger.

“Not dinosaurs again,” she murmured as she recalled one particular time when she and The Doctor had run towards what everyone else had been running from. “Please, not that.”

The escalator and travellator for shopping trolleys and prams had both been stopped automatically when the fire alarm was tripped. The Doctor took the static down escalator four steps at a time. Marie was a little more cautious. The alarms weren’t going off by accident. There was smoke and the glow of fire coming from the lowest level of the shopping centre. Something about the kind of panic exhibited by the fleeing shoppers told her that there was more than just ordinary fire down there.

Despite knowing there could be just about anything going on she was still taken aback by a tribe of long-bearded men dressed in furs and animal skins gathered around a huge camp fire built in what had been a plot of ornamental ferns. They had rigged a kind of spit over the fire and were roasting chickens and joints of meat looted from the nearby Dunne’s supermarket. They had raided the fresh produce section, fortunately. Marie found herself thanking providence that they had not attempted to barbecue frozen chickens. It would just have been too insane.

They had hostages corralled in the pit of a children’s ball pool and guarded with spears and axes. These were mostly security staff from the centre and the manager and two shelf stackers from Dunne’s. One of them was nursing a wounded arm hastily bandaged with the ripped piece of his staff shirt. Another seemed to have tasared himself.

One way or another, this had not been in the job description and they were all in something of a state of shock.

"Does the phrase 'Sons of Parthelón' ring any bells with you?" The Doctor asked. Marie turned to see him standing beside the escalator with a hostage of his own - a young warrior whose beard wasn't quite long enough for birds to nest in.

Nobody had told the terrified warrior that the sonic screwdriver was a tool, not a weapon. The Doctor only had to jiggle it meaningfully to keep him in line.

"Yes, " she answered. "Yes, it does. But...."

"I thought it might. Anyway, first things first. Let's do a bit of hostage exchange.” The Doctor jiggled the sonic screwdriver and the young warrior stepped closer nervously. “What’s your name, sonny?” he asked in an obscure language that bore only a casual relationship with modern Irish. Of course, she heard it in English, her first language, but she recognised what it was meant to be.

“Cían Óg,” he answered.

“Cían Óg,” The Doctor repeated. “Young Cían. Very good name right now, but you’ll have to change it when you get older or it won’t make sense. You can’t be Cían Óg when you’re ancient. What if you get married and your son is Cían, too? He can’t be Cían Óg Óg.”

A stray thought came into Marie’s mind, telling her that it would be Cían Níos Óige – Cían the Even Younger. The Doctor grinned at her as if he had read the thought and appreciated her joining in the nonsense.

“Well, anyway,” he conceded. “Can’t stand around discussing onamastics all day. Come on, young Cían, let’s go and talk to your boss.”

“My father,” Cían corrected him. “Cían Ciallmhar – my father - is leader of our tribe.”

“That’s an even more dangerous name – Cían the Wise. If he turns out to be less than wise, I’ll be making a complaint under the Trades Description Act.”

He brought Cían to the edge of the strange camp. Cían Ciallmhar rose from his place of authority on a wooden dining chair that had been liberated from the household section of Dunne’s. He approached The Doctor cautiously, but with no weapon drawn.

“It’s quite simple,” The Doctor said. “You get your son back in exchange for those men over there who have nothing to do with anything and were just doing their jobs.”

"How came my son to be your prisoner, old man of the iron grey hair and fragile bones?" demanded Cían Ciallmhar. "Is he not warrior enough to fight one such as you whose face tells the saga of decades?"

“Decades?” The Doctor grinned. “Oh, not even close.”

“Sorcery,” answered the son. “I should have slain such a one, otherwise.”

"I tripped him," The Doctor contradicted the young warrior, wiggling one long leg in explanation. "Don’t blame the boy. I’m sure he's been trained well enough in the art of war, just not in the trickery of grey-haired old men. So do you want him back or not? "

"Take these paltroons," Cían Ciallmhar growled, waving the spear carriers away from the prisoners. "Son, take your proper place."

The exchange was made with as little trouble as that. Cían Óg went to sit beside his father's makeshift throne quietly and with downcast gaze while the bewildered security guards and store staff were surrendered to The Doctor.

“Come on, now,” he said to the released prisoners. “Marie, take them out of here. Find whoever thinks they’re in charge outside and tell them it’s a Code 9.”

“It’s a what?” Marie queried.

“Code 9. The person you say it to won’t know what it means either, but somebody at their headquarters will and things will start happening very quickly.”

“All right. But… hang on… do you mean you’re staying here… with that lot… creating a fire hazard and shoplifting?”

“I need to talk to the big man,” The Doctor replied. “You get these civilians to a first aid point and pass on my message. It will all make sense in a little while.”

“Nothing makes sense when I’m with you,” Marie protested, but The Doctor had obviously made up his mind. As she went with the released hostages up the escalator to freedom and fresh air she glanced back once to see The Doctor approaching Ciallmhar with his sonic screwdriver put away and his hands outstretched to show that he came unarmed and in peace.

There was a major incident operation involving all – or at least MOST - of the emergency services outside The Square. Paramedics were dealing with the injuries sustained during the panic stricken evacuation while Gardaí attempted to interview those still standing. The fire service was there but standing idle. They could not enter the building while there were armed men inside. The fact that the fire was under the control of the armed men and being used to cook dinner wasn’t especially reassuring to them. It was still a fire. Thick smoke from it was pouring out through the ventilation system adding to the ominous feel of the situation.

Marie gave her strange message to the most senior Garda on duty, one Inspector Sean Ryan. He was puzzled – even more so when the orders came back virtually handing the operation over to Marie.

“What do I do?” she wondered as she did her best not to look panic stricken. “Seriously? I’m in charge? I’m a teacher.”

“Well, that’s front line policing with the delinquent kids we have in our schools, these days,” Inspector Ryan answered dryly. “Anyway, I was told that somebody called The Doctor was in command here, and in his absence whoever announced the Code 9.”

Marie still had no idea what that was about, but she tried to pretend she did. She decided the less people around the better and gave orders for all the staff and customers evacuated from the Square to be taken to the school where she taught. The assembly hall could contain everyone. The Gardaí could start interviewing witnesses in the classrooms and there were even snack dispensers in the dining room for emergency refreshments. She also exercised her new found powers by sending away the RTE outside broadcast van that had turned up and putting an official embargo on any news stories about the incident.

Just as she was wondering what else she might do, her mobile phone rang.

It was The Doctor.

“You can send in a crew to damp down the camp fire,” he said to her. “I’ve persuaded the Sons of Partholón to come to KFC instead. They think the fries are rubbish, but Cían Ciallmhar loves the hot wings and Cían Óg turns out to be a dab hand with a deep fryer basket. He’s churning out bargain buckets by the… bucket.”

“You took a bronze age tribe of warriors to KFC?” Marie didn’t know whether to be appalled, alarmed, or amused at the idea. At least they weren’t starting fires in the shrubberies, but she was full sure that Cían Óg had never read the Health and Safety warnings for working in a KFC kitchen, and besides, surely they weren’t here just for fast food.

“They’re not,” The Doctor explained. “You said you had heard of the Sons of Partholón.”

“Well, sort of. They’re one of the old legends about the first settlements of humans on this island of Ireland. Allegedly they arrived by sea a few hundred years after the Biblical flood. I suppose that’s really some while after the end of the last ice age and when the British Isles became islands with the rising sea levels, but in the legends its always Old Testament times. They were reputed to be the first brewers in Ireland, establishing grain farms and breweries. But they were also fierce fighters who defended their property. They’re sort of a cliché about Irish men in a way – beer and fighting – it’s like Saturday night up town.”

“I’m saying nothing,” The Doctor commented, quite out of character for himself.

“Well, the legend goes that the whole tribe died, not in a war with their enemy, the Fomhóire, but of a great plague. That’s their connection with Tallaght. The Irish name Tamhlacht means ‘plague pit’ or ‘burial place’…. Taimhleacht Muintere Parthalain is the burial pit of the people of Partholón… their mass grave.”

“So, your home town is built on top of a plague pit,” The Doctor remarked. “There’s got to be a joke in that, somewhere, but I can’t quite think of it just now.”

“I’m sure it’ll come to you. But the thing is, it’s all nonsense. All of the burial sites ever found in this area – and plenty of archaeologists have come to look - date from the Christian era and there is no real evidence that the Partholón ever existed. It’s just one of those fireside stories we had in this country before we had a body of written literature – or television.”

“And the Fomhóire?” The Doctor added.

“The Fomhóire are another mythological tribe of early settlers in Ireland. Unlike the Partholón or the Milesians, or the Tuatha de Dannan, they weren’t tall, strong, beautiful people. The Fomhóire were reputed to be misshapen in all sorts of ghastly ways – and basically, ugly. If a child was born deformed it used to be believed that it was a child of the Fomhóire, put into the womb maliciously. Obviously, modern thinking is a bit kinder about that sort of thing, but the Fomhóire, being rejected as imperfect in that way tended to be more than a little bitter about it. They would fight anyone and anything.”

“And that’s exactly what this is all about,” said The Doctor. “The Sons of Partholón are feasting before their battle with the Fomhóire, who will be camped somewhere else with their own preparations under way.”

“You mean there’s about to be a pre-Christian tribal battle in the streets of modern Tallaght?”

“That’s about it. Except these hairy dudes are not from pre-Christian Ireland. They’re from a parallel Ireland that exists on the other side of an interstitial portal….”

“A what?”

“A magic door to another place,” The Doctor translated. “Like Narnia but much less charming. This other realm, alternate universe, whatever you want to call it, has existed for as long as your one, but it hasn’t progressed technologically past the iron age – well, at least not until Cían Óg got into the fast food business. Somehow or other the tribes have slipped through the portal and intend to continue with their battle plans regardless of who or what might be in their way.”

“So what do we do about that?” Marie asked.

“We have to keep the two tribes from doing battle and keep innocent civilians away from them until the portal re-opens and they go back where they came from.”

“Is that likely to happen? Will it just happen spontaneously, just like that?”

“Yes, it will. But the problem is I don’t know WHEN it might happen – it could be in the next ten minutes or it could be ten hours, ten days….”

Marie sighed. It had to be complicated like that. And there was another nagging question.

“Where IS the other tribe, anyway?” she asked. “The Sons of Partholón arrived in the basement of The Square – so where are their enemies?”

Inspector Ryan had the answer to that.

“We’ve just heard there’s another lot over there in the Stadium,” he told her. “Trying to make a bonfire in the middle of the pitch.”

Marie looked across the car park towards the floodlights overlooking the Tallaght Stadium, the geographically correct but unimaginatively named home of Shamrock Rovers football club. She knew she was going to have to go across there and look. She didn’t want to, but she was in charge, after all.

As she climbed into the back of a Garda car for the short drive around to the stadium entrance she wondered what to expect. She had seen lurid drawings of what the Fomhóire were meant to look like and some even more fanciful descriptions that defied illustration. They were believed to have the heads of goats and bulls and only one leg and one arm each, these growing out of the middle of their chests. She wasn’t sure she was ready to meet such horrors.

As she stepped into the six thousand capacity stadium with the vista of the Wicklow hills beyond it she was at least relieved to see that the tribe ripping up the seats from the stands for their bonfire were a quite normal human shape. They were distinct from the Parthalón in that they were a little shorter and thinner. They wore loincloths over the parts of their body Marie really didn’t want to see and covered the rest of their flesh with tattoos probably made with some variation of that multipurpose dye called ‘wode’.

They were preparing to butcher a goat. Marie presumed that the goat had come through the interstitial portal with them. Shamrock Rovers didn’t usually keep livestock on their pitch.

She really wanted them to stop doing that right in front of her. The goat’s terrified bleats were as loud as their tribal chants, but she didn’t have the option of taking them to a fast food venue.

She did her best. Reluctance to see a goat’s throat slit in front of her overcame her fear of talking to the tribe. She walked right up to the bonfire over the centre spot and engaged in a surreal conversation with the leader, a scrawny man who identified himself as Áed Dubh. His story confirmed The Doctor’s summary of events. His tribe of Fomhóire warriors were making ready to do battle with the Partholón.

“Yes, but what about the goat?”

Black-haired Áed explained to her in his proto-Irish language that the goat sacrifice was necessary to ensure victory in battle – as well as forming the basis of the pre-battle feast.

“But you can’t kill a goat here,” Marie told him. “This is a soccer stadium. They don’t even allow Gaelic football here, let alone goat killing.”

“We need to get them out of here,” the Garda officer told her anxiously. “Goat or no goat, they’re causing a LOT of damage.”

“But where else can they go?” Marie wondered aloud. “The Doctor said they had to be kept apart.”

Then she had an idea, one that might even save the goat if she could organise it quickly.

“No, he didn’t say that. He said they had to be kept from fighting. And… I think I have an idea. Not here, though. Apart from the rules about GAA on soccer grounds, this is the Fomhóire camp. We need a neutral place. I think I know where we can go. We’ll need a couple of buses. I saw the team bus outside here, and there was a No. 75 parked at The Square.”

She called The Doctor back and asked him two questions. First, could he drive a bus.

“I can pilot a TARDIS across time and space,” he answered. “I think I can handle a bus through Tallaght.”

“All right,” Marie confirmed. “Get your lot mobile. I’ll handle this crowd and meet you in fifteen minutes.”

“Are you sure this will work?” asked the Garda officer as he sent one of his subordinates to requisition the Shamrock Rovers’ team bus, which seemed far too nice a vehicle to use for transporting tattooed tribesmen in loincloths who liked to destroy things.

“I’m not sure about anything. I’m ‘in the absence of The Doctor…’ But I think it might work. As long as we can get this lot on the bus.”

The Fomhóire were suspicious of stepping, one by one, up the steps and onto the team bus. Áed insisted on bringing the goat, though he had put away the knife and it was happy to lie down in the carpeted aisle.

It was better behaved than the Fomhóire in most respects. They set about rubbing dirty hands all over the beautifully clean windows and fondling the plush seat backs enviously. Marie’s skill at controlling groups of school children on field trips came into play now and she persuaded them to sit with that special tone of voice that a teacher had to acquire or die in the attempt.

“It’s all right,” she assured them when a Garda sergeant with a PSV licence started the engine. “It’s meant to do that. Yes, the landscape outside the windows is meant to change, too. Sit down properly, facing front, or you’ll fall and hurt yourselves if we have to stop suddenly.”

The journey was a little over four kilometres to the south of Tallaght. Unlike their soccer-playing counterparts, the Gaelic Athletic Association ALWAYS used their imagination in naming their stadia, as long as the name was on the broad theme of Irish nationalism. The GAA grounds in Tallaght were named after Thomas Davis, poet and separatist of the mid-nineteenth century, author of the popular rebel song, A Nation Once Again, which was often sung – though generally with less noble words than Davis intended – on the terraces.

More importantly, there were fields, a stream and trees surrounding the playing pitches, making it easy to keep civilians out of the way.

The No. 75 that usually plied its way between Dun Laoghaire railway station and The Square arrived first. The Sons of Partholón were waiting like a school group against the red brick wall of the changing pavilion as The Doctor boarded the Shamrock Rovers bus. He smiled a piranha-like smile at the bewildered Fomhóire and stood aside while Cían Óg and three of his comrades moved down the aisles distributing buckets of deep fried chicken – their feast before battle.

The goat had a bucket of cold fries which it seemed to find preferable to being a sacrifice. Meanwhile The Doctor put on his souped-up sonic shades – a gesture that made him look like an aging rock star and promised mischief. He rubbed the left top edge of the frame and a brief flash of white light filled the bus for a few seconds. The Fomhóire looked at first puzzled, then eager as he invited them to get off the bus.

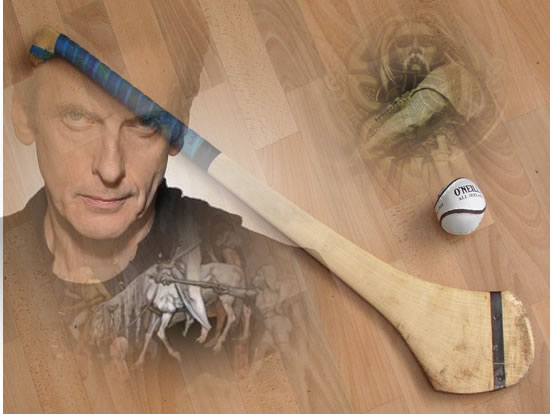

“Is it really a good idea to hand this lot what looks pretty much like a bunch of cudgels?” asked Inspector Ryan as he watched The Doctor distributing Hurley sticks to the two tribes. “Won’t they just wallop each other to death?”

“The trick with the glasses and the lights,” Marie explained. “It’s a bit too Men in Black for my liking, but it basically transmitted the rules of Hurley into their heads. Now they’re off to play the biggest grudge match in the history of the GAA.”

The Garda Sergeant who had driven the team bus now took charge of the goat, which had acquired a GAA pennant around its neck and was still chewing the last of the fries. Everyone else watched curiously as The Doctor led the two tribes onto the pitch.

“I want a good, clean game,” he announced. “No cheating, no biting, no clocking each other round the head with your camáin. And if you need to answer a call of nature, you’ll find what you need in that building over there. You’ll work it out.”

With that, he put a referee’s whistle around his neck and tossed a sliotar – the tough, leather hurley ball - into the air like one who knew exactly what he was doing. He almost certainly did. Marie didn’t even begin to wonder how an alien from something like two hundred and fifty million light years away learnt about a game only ever played by Irish people or their descendants abroad who clung to the traditions of the ‘old country’. He was The Doctor. He just knew these things.

And so did the Partholón and the Fomhóire, now, thanks to The Doctor’s quick tutorial. The best and fittest fifteen of each tribe played the standard thirty-five minutes of a game in which the ball could reach astonishing speeds, launched up and down the field with the ash sticks until it went into the goal for three points or over the bar for one.

After seventy minutes the score was five goals and two points to the Partholón, three goals and eight points to the Fomhóire, or seventeen points each in total. Substitutes were brought on and they set about a further thirty-five minutes, followed by another, and another. Not only was it the strangest Hurley match played in Ireland, but it was also looking like the longest, with neither side ready to give in and the score mounting up on both sides.

After another two hours it was fifteen goals and thirty-five points to the Sons of Partholón and seventeen goals, twenty points to the Fomhóire. The Doctor still looked fresh as a daisy refereeing the match. The goat had settled down to sleep, bored by the Human activity.

Then The Doctor blew his whistle hard. He pointed to a peculiar swirling light that was growing at the far end of the pitch.

“The interstitial portal,” he said as the tribes gathered around him. “Your chance to get home to your families and your brewing. No, leave your sticks. That’s right, put them down there on the grass.”

“What’s the final score?” Marie asked as the two tribes began to walk towards the portal. “I’ve lost count.”

“Partholóns thirty goals, eighty-five points, Fomhóire thirty-two goals, seventy-nine points.”

“A draw,” Marie reckoned after a few moments of mental addition. “Yes, it’s a draw. I’m glad. I really didn’t want either side to be superior. Maybe they’ll feel the same when they get back to their world and work together to build a peaceful society.”

“What about the goat?” asked the sergeant.

“It’s NOT going back with them. They might make him dinner, after all,” Marie insisted.

“He can come home with me,” Inspector Ryan said. “We’ve got a bit of land at the back, and the kids will love it.”

But the goat was not the only one in danger of being left behind. After widening out to the size of a small aircraft hangar the portal was now shrinking again. The Partholóns and the Fomhóire ran to get through it in time. The Doctor urged them along, and though it was touch and go almost all of them were through by the time the portal had reduced to the size of an ordinary garage door.

“My son!” Cían Ciallmhar turned around in a panic. “Where is my son?”

“He must have gone through already,” The Doctor answered him. “Go on, quickly. It’s your only chance.”

But Ciallmhar wouldn’t go. He was sure his son was still here.

“There he is,” Marie called as Cían Óg came from the place The Doctor had told them to go when nature called. He saw his father’s urgency and began to run. The two men were only feet away when The Doctor dashed in front of them and pushed them back.

“Too late,” he said. “You’d leave half of yourselves behind. You don’t want to do that.”

Father and son were both stricken with the realisation that they were stranded in a strange world where chickens had multiple limbs and were delicious cooked in boiling oil.

“You could take them in the TARDIS, couldn’t you?” Marie said to The Doctor.

“No,” he answered. “Back in time, back to another planet, yes. But not to an alternative universe. That’s too dangerous for the old girl. I had a hell of a struggle once before in an alternative London where the rich had Zeppelins. No, Ciallmhar, old chap, young Cían, I’m afraid you’re going to have to adapt to a whole new life. I’ve got some friends in high places, an organisation called U.N.I.T. They can sort you out….”

“Will I be able to play Hurley again?” Cían Óg asked.

“Yes, you will,” Marie assured him. “If that is what you want to do.”

“Will there be ‘bargain buckets’?” Ciallmhar queried.

“If that’s what you want, I am sure it can be arranged, too,” The Doctor told him. “Maybe we can sort it out for young Cían to manage a branch. Hot wings for tea any time you like.”

That idea pleased Ciallmhar, though the more serious aspects of his predicament did worry him, still.

“My people….”

“They’ll be all right,” Marie assured him.

“Donál Mhór will take your place, father,” Cían Óg said. “He will guide them well.”

“There you go, then,” The Doctor told them. “Big Donald will sort them all out. Come on, now. Until my friends get here, let’s go and eat some other traditional Irish food that I know you’re going to like. It’s called a donner kebab.”

|

|

|