Late October in Paris meant trees turning interesting colours and pearly grey skies sometimes accompanied by sharp winds and rainy days that no amount of colourful brollies could cheer.

For those who could afford warm coats and who could go from an apartment lobby to a taxi and from there to a restaurant or theatre or art gallery it wasn't so bad. For them these years of the early nineteen-thirties were still 'les années follies' – the 'crazy years' when the lights stayed bright and the dancing went on until dawn.

But as she travelled through the damp streets of Paris Marion couldn't help noticing plenty of people without taxis, without umbrellas, some of them without overcoats, for whom 'les années follies' weren't quite so joyful and easy- going.

"There is unemployment in your own time, too," Kristoph whispered to her. "There are few societies that have ever achieved the sort of economic stability that more than one generation can count on. You don't have to feel guilty for your own comfort and ease. You've earned the right to travel in the dry."

He was whispering because they weren't alone. They were in the company of one of the literary luminaries they had partied with in Menton. On the train back to Paris, despite avoiding him on the Riviera, Marion had finally found herself in conversation with the Irish playwright, Samuel Beckett, and though she still couldn't enjoy any of his work, she did find him pleasant company with a dry wit that appealed to her.

He obviously felt the same way since he invited her and Kristoph to stay a few days in Paris with him before they continued on to Calais.

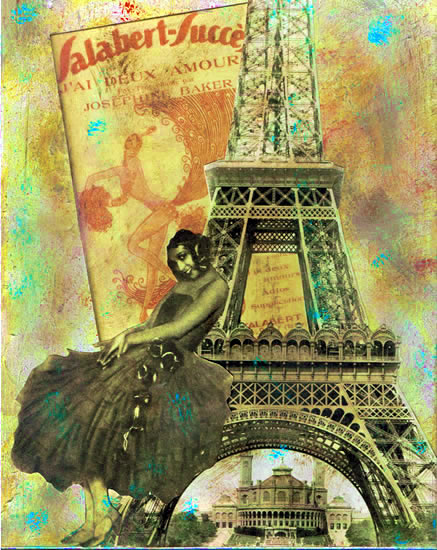

They accepted the offer gladly, and for a week, now, Mr Beckett had been their guide to the still bright lights of Paris. He brought them to the Moulin Rouge and its legendary and spectacular burlesque, and to the Folies Bergère, where the famous American dancer, Josephine Baker was still performing, some eight years after her Paris début. Marion enjoyed both, especially a legend like Miss Baker who she had only seen before in a few very old pieces of archived film. Seeing her in a vibrant, colourful and deliberately risqué review was the kind of thing that made time travel wonderful for her.

This afternoon, despite the rain, they were heading to the Louvre. Somehow, Mr Beckett had come to think that Marion had never been there, before. He talked about the great art she would see with enthusiasm. Marion had been on the point of saying that generally speaking she liked the modern art at the Museé d'Orsay better than the older treasures of the Louvre before she remembered that the d'Orsay wasn't opened until the mid-nineteen-eighties. At this time it was still a busy railway station and a serious temporal faux lax.

Of course, she had visited the Louvre in the early twenty-first century when it had undergone a huge programme of modernisation including the building of the huge glass pyramid entrance and the opening up of a huge underground space beneath the courtyard. In this time nobody, not even the most avant-garde thinkers who inhabited Paris could imagine changing the look of the famous monument so dramatically.

The paintings were displayed very differently in this time, too. The tendency was to fill every wall with as many paintings as possible, side by side and one above another. In this way, Marion supposed, many more pictures could be displayed, instead of keeping a lot of them in archives, but it was quite distracting to see so much at once, and the paintings that were above others were hard to see. Although she identified a number of very fine paintings by great artists that she had not seen on her later visit, Marion thought, on the whole, it was better to have a few paintings on each wall, and at a comfortable eye level. She thought she could appreciate each work more fully that way.

The Mona Lisa, the painting EVERYONE came to see, wasn't where it was in her time. Then it was in the Salle d'Etats, on a wall by itself, behind bullet proof glass and a state of the art security system.

Now, it was in the seventeenth century Salon Carré, displayed in a long row of paintings, and looking almost unimportant among many large canvases depicting great historical subjects. Without the glass and the security, the rope line to keep the tourists moving, it was even more incredible that this was such a uniquely famous painting.

Marion commented on that fact. Mr Beckett laughed softly.

"Well, in fact, up until just before the Great War it wasn't hugely famous except among the intelligentsia. It was regarded as a fine work by Da Vinci, one of the greatest Renaissance artists, but only one among so many great works. When it was stolen in 1911, and the publicity surrounding the theft, it achieved notoriety. After it was returned, everyone wanted to see the one painting they had all heard of, from crowned heads to the great unwashed."

Marion knew about the theft. When she was at university in Liverpool she went to a guest lecture about the treasures of the Louvre. The art was displayed on a large screen in the main lecture theatre and in some cases – Mona Lisa included – looked bigger, more colourful and more impressive that way.

"Picasso was accused of stealing it," she remembered. "He was innocent, of course. It turned out to be a misinformed and rather disgruntled Italian who thought it ought to be returned to its home country."

"Pablo will be pleased that you exonerate him," Beckett said with a wry smile.

"Oh!" Marion exclaimed. "Oh, don't tell me he's a friend of yours?"

"Well, an acquaintance, a friend of a friend, at least," Beckett admitted. "Though I think I could arrange a visit to his studio if you would like to see a great living artist after studying all these dead ones."

"Really?" Marion tried not to sound too excited. How famous WAS Picasso in this time? It was several years before he painted Guernica, of course. That was fixed in history by the terrible events depicted. But some of his other famous works predated that. She tried to remember which ones, but although she could name several of Picasso's works, and would recognise a few more on sight, she didn’t know the dates when they were painted or exactly when his reputation as a 'great artist' of the twentieth century was established.

Anyway, she kept her composure and tried not to let the prospect of meeting so great a man spoil a leisurely exploration of the Louvre's many galleries crowded with the treasures of a nation going back centuries.

The rain was heavier and clouds darker when they emerged, and the luxury of taking a taxi was all the more appreciated as they travelled to Rue La Boétie, a street of seven and eight storey apartments and offices that seemed to cut off the sky on both sides making it feel quite dark on such a rainy day.

Picasso's home and studio at the top of no. 23 Rue La Boétie had wide windows that captured the best of the light even on a dismal day. Their welcome was cordial. Beckett introduced Marion and Kristoph as wealthy English art appreciators. Pablo Picasso, by now a wiry and grey haired man in his mid-fifties, in his turn introduced them to another visitor that afternoon, his friend and art dealer, Paul Rosenberg.

"If you were thinking of buying a Picasso work, you had best come along to my gallery, two doors along this very street," Mr Rosenberg told them. "Apart from anything else, I get the commission on the sale."

He winked and smiled as he said that and Marion smiled back. He was, of course, telling the truth as well as making a friendly joke. Beckett and Picasso both laughed.

"Paul has always been a shrewd businessman," Picasso said in a good natured way. "He will get a good price out of you. A better one than I would. Even after all this time, I am never sure what my pictures are worth to other people."

"I am a shrewd art buyer," Kristoph answered. "We shall decide between us what price to put upon your work. But my wife is interested in seeing your studio and your works in progress."

Picasso smiled again at Marion and she recalled that he was a man with a string of mistresses by this time in his life. But on this occasion at least he was not trying to seduce anyone. He behaved perfectly gentlemanly towards her as he showed her where he worked every day whether by natural or artificial light. Most of the canvases he had most recently finished were in that angular and highly symbolic style he was most famous for, the sort that would most easily be identified as 'Picasso' even by the least trained observer.

Marion would have readily confessed that she found the symbolism hard work, and that a lifelike portrait such as the Mona Lisa was much easier to readily understand, but not to the man himself, and not when he was showing her his work himself.

"I certainly DO want to buy one of your paintings," she genuinely admitted when she had seen all there was to be seen and they were drinking coffee in the busy and slightly untidy drawing room of the apartment with the rain as a constant background to the conversation. "Maybe more than one if my husband is in generous mood and Mr Rosenberg doesn't strike too hard a bargain."

Mr Rosenberg at once offered to take them to the gallery. It was agreed that Mr Beckett should stay with the artist and drink coffee while they went to conduct the business transaction. People of artistic temperament, Beckett declared, should be spared the mundane fact of the buying and selling of their soul's output.

That was just the sort of thing Beckett WOULD say, Marion thought as they made their way out of the apartment and down an old-fashioned cage style lift to the foyer. They walked under Mr Rosenberg's big black umbrella the very short way to the gallery.

Several of Picasso's works were displayed in the gallery, as well as works by Henri Matisse and Georges Braque and other contemporary artists who lived and worked in Paris in this decade. Most were hung in frames on the walls, not quite so crowded as at the Louvre, but still jostling each other for space. Others were on free standing easels to give them more prominence.

Marion looked at them all carefully and equally carefully didn't look at or ask about, any prices. She was, in fact, starting to think Mr Beckett's remark wasn't just a glib and throwaway line from a playwright who liked to manipulate words. There really was a lot of heart and soul in this art and putting a price on it – even a good price - felt cruel.

She chose two Picasso works, one entitled 'reclining nude' that was apparently his current mistress - though in the abstract and symbolic form it took some imagination to see it as a nude figure let alone any particular woman. The other was a very angular 'still life' of a blue and green tea set that Marion recalled seeing in the drawing room when they were having coffee.

She also chose a Matisse 'still life' which was anything but still with the 'cloth' background seeming to flow like water around the arrangement of flower vase and a jug.

She was already planning where the three paintings might hang in their home on Gallifrey.

She still didn't ask how much the paintings cost. Kristoph paid by cheque and arranged for the paintings to be sent to Calais by train to await them along with the TARDIS when their Parisian stay was over.

Meantime they would drink coffee with Picasso and Beckett again. Mr Rosenberg lent them his umbrella to walk from 21 to 23 Rue La Boétie without getting wet.

"Mr Rosenberg is Jewish, isn't he?" Marion said as they awaited the lift in the rather draughty foyer. "I took a while catching on, even with such an obvious surname. Beckett and Picasso were both making a joke about it when they talked about 'shrewd businessmen', weren't they?"

"A mild one, in the presence of a good friend who was not offended," Kristoph pointed out. "Although, by the early twentieth century, people were a little more sensitive to such things and might think they were being anti-semitic."

Yes… but… The Nazis arrive in Paris in 1940. Will he….:

"Mr Rosenberg is shrewd in more ways than money and fine art," Kristoph assured her. "He will know when it is time to leave Paris. He and his family and a lot of the art will make it to America. Sadly, lot more of the art will fall into the hands of the Nazis and even by the end of the century much of the Rosenberg collection will still be missing."

"I'm not sure I care about that. As precious as the art is, people are more important. I'm glad… I know millions of people will be hurt, but I'm glad people I've met will be all right, at least. I'm glad Mr Rosenberg will get away in time, and that Mr Beckett is going to be a hero, helping others to escape. I'm glad Picasso will keep painting the sort of art the Nazis hate and they'll all still be alive at the end of it."

"So am I," Kristoph told her as he opened the lift gate. "Between them they are a small victory against a huge and terrible future that is still to come for this world of yours. Let us go and drink coffee with them again for a few more untroubled hours."

"Yes," Marion agreed. "I would like to do that."

|

|

|