It was just before dawn on the southern plain. In his private tent, Kristoph roused himself and dressed before going to wake the youngsters he had taken on a field trip.

The smallest of the tents was for the only female member of the group. The flap was open and the sleeping bag clearly slept in but currently empty.

He turned about, slightly worried, before he caught sight of Verema Ges walking along the base of the mighty Demos’ Bluff, the second highest escarpment on the plain next to Melchus Bluff where he regularly brought the hang gliding ‘club’. Demos had its own points of interest for an educational as well as entertaining weekend out of the regular school routine.

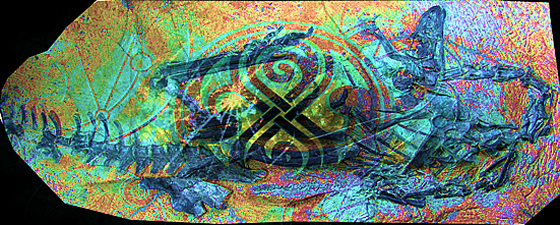

Verema was looking at one of those points of interest in the very earliest rays of sun. The huge fossilised skeleton of a long extinct reptile had been named Pazithi Reptillius some time in his grandfather’s generation – he who fought living, breathing dragons and would not have thought much of long dead ones.

The creature was fossilised lying down and the length from its great tail to the tip of its nose had been measured as seventy-five feet. Verama was walking that length in the slowly lightening dawn. The early rays of sunlight caught the side of the Bluff obliquely and every fine detail of the preserved bone structure leapt out of the surrounding stone as if it was exquisitely carved bas relief. This was what the girl had risen early to see. She reached out her hand as if to touch the sun-warmed fossil but stopped a millimetre or so from the surface as if knowing that actual contact was forbidden.

Kristoph watched as Verema walked the length of the fossil and turned to walk back again before he revealed that he had been watching her. She was startled and a little worried when he quietly called out her.

“Don’t worry,” he told her. “There are rules in the academies about when student’s go to bed, but I’ve never heard of anyone being in trouble for getting up early.”

“I wanted to wash and dress before the boys were up,” she said. “They are so noisy about it. And I thought to see the sun come up on the Bluff. I had heard that it was impressive.”

“Indeed, it is,” Kristoph said. “My father brought me to see it when I was a very young boy. I had trouble staying awake to enjoy the sunrise. He carried me on his shoulders from nose to tail of our Pazithi Reptillius.”

Verema smiled politely, obviously having trouble visualising somebody so much older than her as a small boy.

“Was the Pazithi Reptillius fossil first revealed when you were a child?” she asked cautiously.

“No, it was in my grandfather’s first regeneration,” Kristoph answered. “That would be about two thousand years before my father was born. Don’t try to do the maths. It just makes us all feel old. You’re probably wondering how the fossil has stood the test of so many hard, cold winters and blistering summers without eroding? I’m afraid that’s a bit of Time Lord technology. A very thin environmental shield covers the whole Bluff.” Verema gave him a bemused glance. “Yes, that was the slight fizzing you felt in your fingertips when you reached out. And yes, it IS cheating in a way. There was a huge debate in the Panopticon when my father was at the Prydonian Academy. The question was whether to fully excavate these fossil wonders of our ancient past and allow the Bluff to erode naturally or to preserve it as it was. The preservation camp won. My father has always sided with the natural erosion view. I think I agree with him in principle, but as a teacher, it is rather more fun bringing youngsters out here to the Bluff than to what you would all regard as a stuffy museum full of old bones.”

He smiled as he spoke and Verema laughed politely.

“Let’s rouse those lazy boys and break out breakfast rations before the sun gets any higher,” Kristoph added. “There’s a lot more to see and we don’t want them to miss out.”

The boys were starting to rouse themselves, but they were far from washed and dressed and Kristoph backed Verema when she stoutly refused to make the breakfast just because she was up first.

It was a matter of principle, really. There wasn’t much hard work involved. The cereal and milk were in sealed ration packs and so were the bacon and beans, the only difference being that the cereal packs automatically cooled and the bacon and beans heated up in their containers. Wafer sized rehydration packs turned into toast with butter and marmalade already spread. The coffee heated itself in the disposable cups. Kristoph certainly regarded this kind of breakfast as ‘cheating’, but not only did it make the gender role argument redundant, but it made for light travelling and no need to forage.

It was also easy to clean up afterwards. All the food containers crumpled into palm sized balls of biodegradable material that could be buried along with the slightly larger sealed receptacle from the toilet tent. The short straw for that task was drawn by young Arcalian, Solace Andana. It was pure chance, but Kristoph thought it no bad thing that the young Newblood boy got the ‘menial’ task while the brothers, Herra and Marr Vane, and Nura Beize, three Caretakers who were part of the scholarship scheme at the Desert Camp joined Verema in tidying up the camp and preparing the equipment for the day’s adventure. He spared a thought for Andana’s former Arcalian schoolfriend, Ginnell Dúccesci, who had already learnt the value to the soul of menial work.

The primary equipment excited all of the students. They carefully studied the contoured boards just wide enough to stand upright upon and worked out how they operated.

“Thought controlled anti-grav boards?” Solace queried. “I thought we’d be climbing the Bluff with ordinary equipment.”

“That’s not possible,” Verema responded to him. “Demos’ Bluff has been preserved to prevent erosion. So we can’t touch it. We certainly can’t stick crampons into the rock and swing ourselves up on them.”

The Marr brothers were already ahead of their comrades. They took to the boards as if born to them and had learnt to do complex manoeuvres while hovering a foot above the ground even as the others were still grasping standing up straight.

“Well done, boys,” Kristoph said to them. “On Human worlds you would be champion skate boarders. Don’t do any of those stunts when we get higher up, though. There will be no sympathy if you fall off.”

The boys laughed nervously, not certain if their teacher meant that comment.

“If everyone knows how to balance, now, we’ll make a start. No, we will CARRY our boards to the bottom of the Bluff. I’m sure you all want a close look at the great beast, first, anyway.”

They did. More than a passing interest in palaeontology was the reason they had all signed up for this field trip. All of them were thrilled to be able to get within inches of Pazithi Reptillius. The Vane brothers used their anti-grav boards to measure the fossil from end to end, triangulating their positions while hovering at tail and nose ends. The others were content to count the number of huge ribs. Even Andana Solace was humbled when he hovered beside the huge area that would have been the stomach cavity and realised what a small snack he would have made.

“He WAS a carnivore, of course?” Solace asked.

“SHE absolutely was,” Verema answered him. “You missed a vital point in class. All of the great lizards of the Proto-Alleghessy era were female. They reproduced asexually.”

As the only female on the field trip Verema enjoyed the moment or two of reflection among the male students including Nura Beize’s confusion about how that method of reproduction worked.

“You’re a bit old for the facts of life, son,” Kristoph told him gently. “Should you ever consider a career in the Diplomatic Corps, you might as well know that quite a number of sentient races in the universe have evolved that way. The Haollstromnians are probably the most interesting of them. They retained the ability and desire to enjoy each other’s company separate to the reproductive process.”

That puzzled all of the youngsters until the penny dropped for Marr Vane.

“They value LOVE!” he exclaimed.

“As should any sentient species that wants to rise above the Sontaran battalion nurseries,” Kristoph pointed out. “And speaking of rising above, shall we test our heads for heights and look at the finest example of the Mezzo-Alleghessy era?”

There were fossils of various sizes and shapes in almost every part of the Bluff, forming a perfectly linear story of the evolution of life on Gallifrey, but after the great Pazithi Reptillius, the most exciting sight was the preserved form of Pazithi Fortis Volatilis.

Fifty feet high on their anti-grav boards all of the students span around to watch a Pazithi Eagle soaring in the yellow sky. Those magnificent birds could have wings at least a metre long, but the prehistoric creature that bridged the evolutionary divide between reptile and bird had a wingspan of eight metres. Those wings had been broken in the death of the example fossilised in the limestone of Demos’ Bluff, but it was easy to imagine it flying above the tropical forests believed to have covered the southern plain in the Mezzo-Alleghessy epoch.

“I wish I could fly with it,” Verema sighed.

“Lean further back on your board and you might do so, very briefly,” Kristoph warned. “Save flying for the hang-gliding weekends.”

Verema adjusted her posture before they rose further up the Bluff, stopping to examine a strata full of fossilised crustaceans that provided evidence of a rise in sea levels that turned the land into ocean for at least a millennium.

“Rising temperatures, melting poles, the drowning of the land between them brought an end to the age of the giant reptiles,” Kristoph reminded the students. “The higher strata contain no large reptiles, only the smaller mammals that gained a foothold when the land was exposed again and the temperate climate returned.”

The students asked the sort of questions about why the climate changed so drastically that he expected of them. He answered them as well as he could. Not even the most advanced retro-climatologists were entirely sure of the cause. The most likely theory was the eruption of a super caldera under the south pole wiping out the ice cap, but the fact that the temperatures rose was a puzzle. Kristoph explained to his students the extinction event on Earth that had caused the same destruction of large reptiles when ash and dust was thrown up into the atmosphere blotting out the sun and plunging the planet into an extended period of darkness and cold. That had not happened on Gallifrey. The theory was incomplete.

“Divine Rassilonians like my Uncle Gregir believe Rassilon caused it to happen to destroy the great reptiles and make the land fertile so that his own children would thrive,” Nura said.

Kristoph didn’t say anything about that. The belief that Rassilon was a Deity who had been involved in the creation and development of the planet before the sentient species evolved was only a small cult exclusively found in the Caretaker communities. For generations the High Council had chosen to ignore the ‘teachings’ of the ‘DivRas’s' as they were colloquially known. As a strategy for countering a ‘religion’ in the midst of a society without a recognised national religion it had proved a better policy than trying to discredit or suppress them. They were slowly dwindling through intermarriage and education.

Kristoph acknowledged that the fossil record at Demos’ Bluff could prove the DivRas belief just as much as it did the rational, science-based convictions of most Gallifreyans, but he didn’t really want to prolong the discussion. He was glad when the students turned their attention to the examples of smaller, mammalian life fossilised in the upper strata. They included a vole-shaped creature the size of a pig - called the Gondua, a smaller rat-like Paden of which there was a large fossilised colony, and the Steth Leonate, ancestor of all varieties of modern plains Leonate.

“The mammals are a bit… boring… after the reptiles, though,” Herre admitted when they reached the top of the Bluff and sat with a magnificent vista stretching before them to eat chocolate rations and drink rehydrated and cooled fruit juice.

“I don’t think you’d want to call any sort of Leonate ‘boring’ to its face,” Verema told him to the amusement of all before moving on to what she felt was an important point. “Do you think, though, if the land had not flooded – for whatever reason – our ancient ancestors could have been reptilian, not mammalian?”

“Certainly,” Kristoph answered. “This is something else you realise in the Diplomatic Service. I’ve sat next to reptilian species at banquets on many occasions. Fortunately, MOST of those who have evolved to the point where they HAVE intergalactic diplomatic relations have generally developed sophisticated eating habits.”

“Only MOST?” Solace asked and everyone paused in their mid-morning snack to consider what might be considered ‘food’ to a sentient reptile.

“That’s why nobody considers the Diplomatic Corps a ‘soft’ career choice,” Kristoph told them. Laughter again rang out over the top of Demos’ Bluff as the students rested and prepared for the next part of their field trip after a start that ticked all the boxes in terms of education and enjoyment.

|

|

|